Leon Wieseltier: “Her intuition is right: Czesław Miłosz and California are indeed a chapter in each other’s history.”

Wednesday, March 30th, 2022

The Book Haven has been pretty silent on our our newest book, Czesław Miłosz: A California Life. Let’s end that now, and begin catching up. Here are the words from one of America’s foremost critics, Leon Wieseltier: “Cynthia Haven’s book is delicious. She evokes so much so vividly and so intelligently; for me her pages were a restoration of a richer and less lonely time. And her intuition is right: Czeslaw Milosz and California are indeed a chapter in each other’s history.”

From Cory Oldweiler over at the Los Angeles Review or Books:

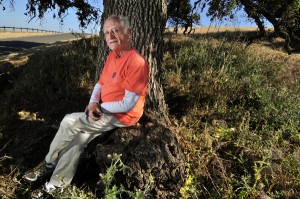

The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz dubbed Dante “a patron saint of all poets in exile” and, as an exile himself for much of his life, likely could relate to both the Florentine’s proud defiance and his urge to seek some measure of solace in the constancy of the natural world. When, in 1960, Miłosz moved to the United States, accepting a teaching position at UC Berkeley, nature was very much on his mind. He was already living in exile, having defected to France nearly a decade earlier, but he had not escaped the haze of history that hung heavily over postwar Europe. The past was integral to Miłosz’s writing throughout his career, especially the horror he witnessed so viscerally in wartime Warsaw, but in order to continue to describe it “in such a manner that it is preserved in all its old tangle of good and evil, of despair and hope,” he had to soar above it, as he put it in 1980, after winning the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Miłosz felt that the United States, specifically the American West, could provide that lofty vantage, that distance, that relative stability from the “demoniac doings of History.” He would live in the Golden State for 40 years, from 1960 to 2000, but according to Czeslaw Miłosz: A California Life, Cynthia Haven’s deeply considered new biography of the poet, Miłosz’s move to America was predicated on a fundamental error. “In immigrating to the United States, and specifically to California in 1960,” Haven writes, “he thought he was coming to the timeless world of nature. However, Berkeley was about to become a lightning rod for […] the world of change […] and he would be in the thick of it.”

He concludes:

Haven lets us into her thought processes, even when she is questioning them, and lovingly recreates conversations — in the relative present, at a café with Robert Hass as they thumb through Miłosz’s 2001 volume New and Collected Poems; and in the recent past, at Miłosz’s Grizzly Peak home as the poet drinks bourbon and chats with friends into the wee hours.

Miłosz, writing in his ABC’s, did not place much faith in biographies: “Obviously, all biographies are false, not excluding my own. […] They are false because their individual chapters are linked according to a predetermined scheme, whereas in fact they were connected differently, only no one knows how.” Haven does not possess any magical insight into those linkages in Miłosz’s timeline, but by giving relatively free rein to her decades of contemplation, she often achieves what Miłosz believed to be the only redeeming value of biographies, namely that “they allow one to more or less recreate the era in which a given life was lived.” In this case, she evokes A California Life that soared high above an era of inescapable change.

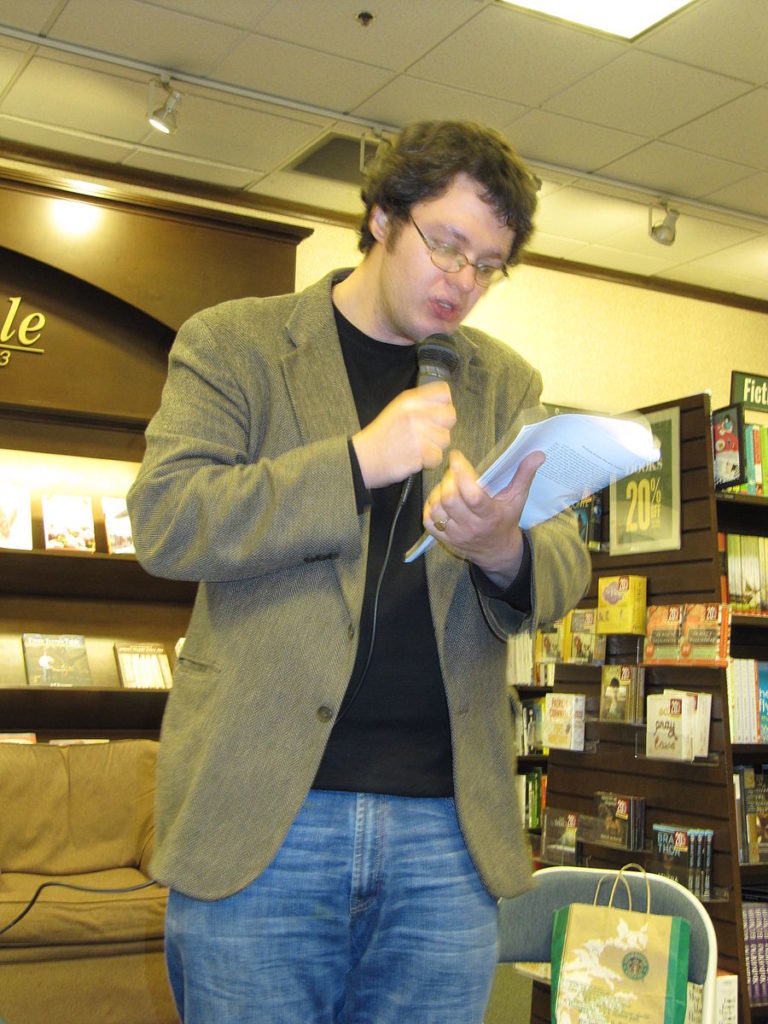

There’s more! Lots more! Over at the National Review‘s “Great Book” series, I have a podcast interview with John Miller about The Captive Mind, Miłosz’s examination of the human psyche under totalitarianism. It’s his bestselling book, the only book of his that has never gone out of print. Listen to it before it disappeared behind a paywall in early May: it’s here. Over at City Lights Bookstore, of Allen Ginsberg fame, I team up with my friend James Marcus, former editor of Harper’s and author of Amazonia: Five Years at the Epicenter of the Dot.Com Juggernaut, for a video conversation to discuss Czesław Miłosz: A California Life. James is great fun. Go here. My Spotify/Apple Podcasts interview with xx over at The Athenaeum is here.

Stay tuned in the weeks to come for more about Czesław Miłosz: A California Life, out with Heyday Books in Berkeley.