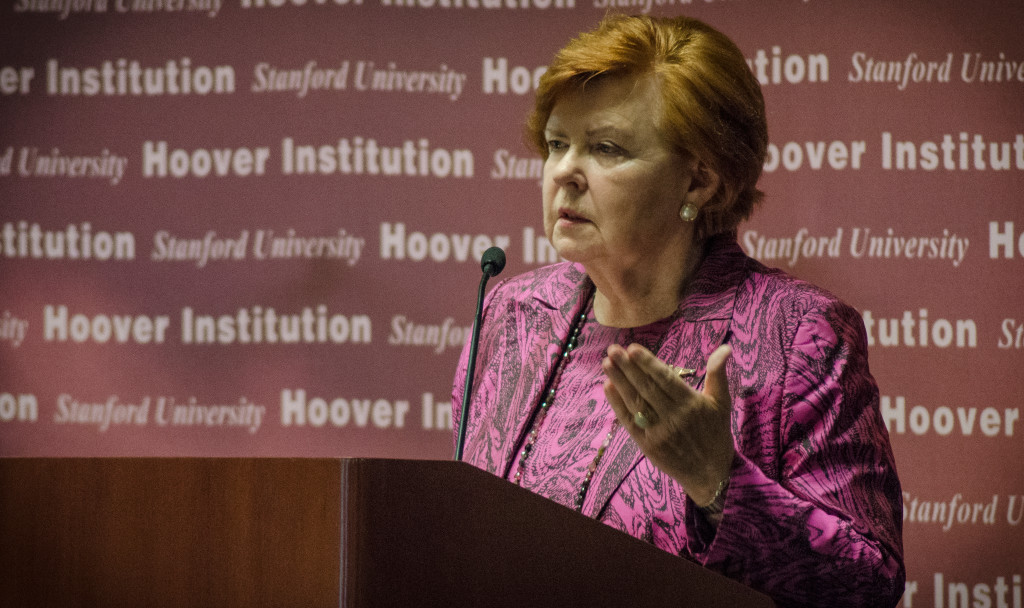

Since regaining independence in 1991, Estonia has attracted international acclaim in many spheres, but notably in high-tech with the invention of Skype, the development of e-government, and the decision to teach computer coding to school children. In recent weeks, it has been back in the news, but this time because of Russia’s illegal annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula. Estonia and her Baltic neighbors worry that their neighbor’s expansionist actions could mean that they are next. After all, in 1940, the Soviet Union swallowed up Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and the nations ceased to exist for five decades. Balts know that in 2005, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin described the breakup of the Soviet Union as the “greatest geopolitical disaster of the last century.”

Since regaining independence in 1991, Estonia has attracted international acclaim in many spheres, but notably in high-tech with the invention of Skype, the development of e-government, and the decision to teach computer coding to school children. In recent weeks, it has been back in the news, but this time because of Russia’s illegal annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula. Estonia and her Baltic neighbors worry that their neighbor’s expansionist actions could mean that they are next. After all, in 1940, the Soviet Union swallowed up Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and the nations ceased to exist for five decades. Balts know that in 2005, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin described the breakup of the Soviet Union as the “greatest geopolitical disaster of the last century.”

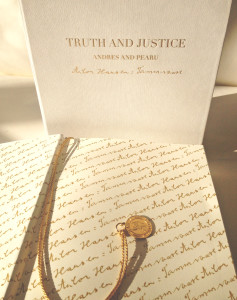

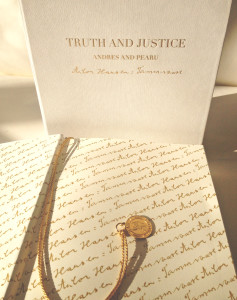

This contemporary backdrop makes the translation of Anton Hansen Tammsaare’s Tõde ja õigus or Truth and Justice timely and relevant for international observers. Expanding access to a nation’s literary canon, particularly one that is not well known in the West, is critical for understanding that country’s values and worldview. (Read more about the effort here, or go to the publisher’s website, which offers a free pdf version of the book’s first chapter and ordering information for the luxury collector’s edition, here. The page also includes background on the book and author: “Written during the rise of dictators – Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Benito Mussolini – the social epic captures the evolution of Estonia from Tsarist province to independent state. Based partly on the author’s own life, Truth and Justice explores the contrast between the urban middle class and the hard-working peasantry. Tammsaare draws an ironic portrait of urban intellectuals who have absorbed the middle and upper class mores and abandoned their moral principles.”

.

This is the story of how the translation of Truth and Justice happened, as told by my friend and colleague, the journalist Lisa Trei, who is the daughter of one of the translators, the late Alan Trei.

.

Translator and daughter

When I moved to Estonia in October 1990 to work as a reporter and teach journalism, I didn’t speak a word of the language or know much about a place known as the “Soviet West.” With its long food lines and Soviet soldiers, it certainly didn’t feel like the West. Despite the challenges of daily life, I longed to connect with and understand the country my grandparents had emigrated from in the 1920s and to which I had moved during the waning days of the Soviet empire. I scoured bookshops and kiosks for anything published about Estonia in English. Very little was available, and anything I could find was usually dull and translated into stilted, awkward prose.

.

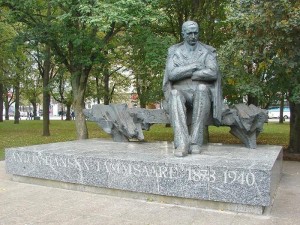

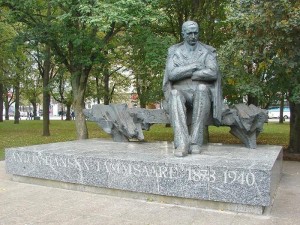

I was familiar with Kalevipoeg, Estonia’s national epic, but I hadn’t read Tõde ja õigus, which is regarded as “The Estonian Novel.” My colleagues at Tartu University and The Estonian Independent talked reverently about its author, Anton Hansen Tammsaare (1878-1940), explaining that he understood the national psyche and, therefore, I should read him. If only I could. The closest I could get to Tammsaare was a statue of him in a park next to Tallinn’s elegant opera house. Truth and Justice was added to the list of books I would read if I ever mastered Estonia’s famously difficult language.

.

I ended up living in Tallinn and Tartu for six years, and witnessed firsthand the collapse of the Soviet Empire and the rebirth of independent Estonia. During that time I married an Estonian, acquired Estonian citizenship, and learned the language—but not well enough to read literature and poetry. The novels that lined the bookshelves of my friends’ homes remained a mystery; a closed door that prevented me from gaining deeper insights into the unspoken cultural and psychological cues of a nation famous for reticence and introspection. I gained first-hand exposure to these traits in my Estonian husband, a man of few words (so few we later divorced). I had already experienced this in my Estonian grandmother, Alice Roost Trei, whom I loved dearly even when she just stared at me in silence as we sat together in her Manhattan kitchen. When I asked her why she did this, her deadpan response was typically Estonian: “There’s nothing better to look at.”

.

As close as she could get before…

Despite an Estonian upbringing, my father inherited the brash countenance of his hometown of New York City. Alan Trei was opinionated, intelligent, and often infuriating. He loved books, reciting poetry, and singing show tunes out of key in the car. While his parents rarely wasted words, my father loved telling stories. But he was also thoughtful. From the mid-60s to the mid-80s, our family lived overseas in five European countries. When people complained about the stereotypical loud Yankee, my father would say, “You don’t hear the quiet ones.”

.

My dad visited me frequently during the years I lived in Estonia. At some point, he met Inna Feldbach, a translator I worked with on stories about Estonia’s ethnic Russians. The early 1990s was a period of great economic, political, and social transition and there was a lot to report on for the international press. Inna spoke fluent Russian and Estonian, and understood the cultural mores of each society. She was an ideal colleague.

.

My father and Inna, who were both divorced, discovered a shared interest in literature. He began courting her and, eventually, they married. Inna was an established book translator in Estonia and my dad, by then retired, moved to Tallinn to live with her. As he became more engaged with Estonia, he developed a curiosity about the fact that one of Estonia’s greatest works of literature had never been translated into English.

.

Taking on the challenging task of translating of Truth and Justice was entirely in character for my dad. He liked adventure—in 1980, for example, he tried to plan a crazy camping trip in the Soviet Union so our American family could attend the Olympics on a budget. It looked like it might happen, much to my American mother’s dismay, until the U.S. boycott of the Games. We were living in Switzerland and I remember the day he came home and announced that the Soviet embassy had told him, “Nyet.”

.

Tammsaare’s farm house, now a museum, in Järvamaa

Later, my dad and I were among the first Westerners to visit the island of Saaremaa. In 1989, it was closed to foreigners and even mainland Estonians had difficulty obtaining permits to visit this militarized, westernmost part of the Soviet Union. But as islander descendants we got permission to go and found the farmhouse that my grandmother had lived in until she emigrated from Estonia in 1929. When my dad returned to the U.S., he convinced a local newspaper to write a story about his plan to become the first Westerner to buy property—his mother’s house—as soon as it was legalized in Soviet Estonia. After independence in 1991, restitution laws made this impossible but my father succeeded, thanks to my mother-in-law, in regaining land awarded to my grandfather for his military service during Estonia’s War of Independence.

.

During summer visits to Estonia in the mid-2000s, dad told me that translating Tõde ja õigus was high on his “bucket list.” He wanted to contribute something important and meaningful to Estonia. For several years, Inna would translate the Estonian text into English and my father would craft sentences that conveyed the subtle depth of Tammsaare’s narrative. In 2006, the PEN American Center recognized the quality of their work by awarding Inna and my dad a prestigious PEN Translation Fund Grant.

.

In reading the finished book, which has been further revised by skilled editors, I am impressed by how well the translation flows. The first book of Truth and Justice effectively draws the reader into the world of Estonian peasantry during the period of National Awakening at the end of the 19th century. Tammsaare understood the strong connection Estonians have always had with the land and how this relationship informs the national character. When it is published, I hope you will enjoy the first book of Truth and Justice, a treatise on the meaning of a human life, and then want more. The remaining books of this classic pentalogy still need to be translated into English.

.

***

.

Lisa Trei was a reporter for The Wall Street Journal Europe, and has also reported for the San Francisco Chronicle, New York Newsday, St. Petersburg Times, The Hartford Courant, the Dallas Morning News, the Toronto Globe & Mail, The Moscow Times, The Estonian Independent, and others. She taught journalism at Tartu University between 1990 and 1995. She is a former Fulbright Fellowship to Estonia, and received a Soros Award to organize the first-ever conference on investigative reporting in Estonia and she also wrote and edited an Estonian-language handbook on the subject. She was awarded the Milena Jesenska Fellowship in 2008 to report on security issues in Estonia.

Lisa Trei was a reporter for The Wall Street Journal Europe, and has also reported for the San Francisco Chronicle, New York Newsday, St. Petersburg Times, The Hartford Courant, the Dallas Morning News, the Toronto Globe & Mail, The Moscow Times, The Estonian Independent, and others. She taught journalism at Tartu University between 1990 and 1995. She is a former Fulbright Fellowship to Estonia, and received a Soros Award to organize the first-ever conference on investigative reporting in Estonia and she also wrote and edited an Estonian-language handbook on the subject. She was awarded the Milena Jesenska Fellowship in 2008 to report on security issues in Estonia.