M.G. Stephens on Brodsky: “It is the voice that seduces us”

Thursday, October 13th, 2011Occasionally I run across forgotten treasures at the bottom of my heavy backpack, which I carry like a creature from the Fourth Circle of the Inferno.

For example, today I retrieved, and finally read, M.G. Stephens‘s “Sunday Morning at the Marlin Cafe,” which was published in Ploughshares in autumn 2008. The London writer had sent it to me months ago, and I had neglected this riveting memoir of meeting Joseph Brodsky in a “sleazy, reeky old man’s dive” on Broadway near Columbia University, when he was “moments away from being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.”

Meeting the poet could be life-changing – and seems to have been so for Stephens, who was seeking “a Sunday morning hangover drink.”

The two quickly grappled over the HBO offering Richard Pryor. Said Joseph: “This man is terrible. How do you allow him on your media? To rant and rave in this obnoxious and vulgar manner. America has become a decadent country. You have no restraints. You allow this vulgarity – this profanity – to be spread throughout the world. It is like a virus. A contagion. It is an insult. It is …”

The burly bartender intervened: “Because he’s funny. That’s why. He’s funny. And you’re not. You ain’t funny at all. You’re a royal pain in the ass. That’s what you are. Am I making myself clear?”

He was, but the narrator tried to remonstrate that Pryor is a modern Aristophanes. J.B. would have none of it:

At first he ignored me. Then he said, “It is nothing like Aristophanes. Language is the domain of poets. The Greek dramatists were all poets first and playwrights second. Language was their domain. This fellow is not using language. He is speaking words – vulgar words from the street. No, no, you’re wrong. This has nothing to do with Aristophanes.”

At first I mistrusted the whole tale. As I recalled, the Nobel poet didn’t care for vodka, preferring wine. And it was hard to see him as a Sunday morning drunk. But what convinced me is the way Stephens is haunted by the episode, going on to discover, and fall in love with, Brodsky’s prose. Decades later, he’s still arguing with the poet, turning the brief encounter over and over again in his mind.

At first I mistrusted the whole tale. As I recalled, the Nobel poet didn’t care for vodka, preferring wine. And it was hard to see him as a Sunday morning drunk. But what convinced me is the way Stephens is haunted by the episode, going on to discover, and fall in love with, Brodsky’s prose. Decades later, he’s still arguing with the poet, turning the brief encounter over and over again in his mind.

Well, Joseph could have that effect on you.

And so I am turning Stephens’s provocative piece over and over in my mind. I don’t agree with all of Stephens’s contentions – he finds Joseph’s poetry “too formal, too academic, too patrician.” Academic? J.B. was an auto-didact who dropped out of school at 15, a Leningrad street fighter who was roughed up by the KGB. And I don’t necessarily agree with this argument … at least I’m not sure I do:

Isn’t that always the case with a good personal essay? It is the voice that seduces us, not the content; it is the rhythm of the prose that draws us in, not the thoughts necessarily. At least I am more often attracted to an essay by the prose style. It is only later that the content registers. This has been true for me reading Thoreau just as it has been reading Orwell. In fact, it is the rhythm of Emerson‘s essays that I most struggle with, not the thoughts themselves… Brodsky’s prose rhythms were so good that they drew me into his orbit.

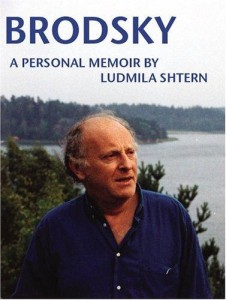

A contrary p.o.v.: Ludmila Shtern recalled in her memoir an uneducated peasant, “Uncle Grisha,” who was listening to a very young Brodsky read one night at her Leningrad home, crossing himself repeatedly during the reading. “I don’t understand poetry. I’ve only had four years of school. But the issue isn’t the poetry, it’s the thoughts,” he explained, “your Joseph spoke so many thoughts last night, most of them wouldn’t have even occurred to another person even if they lived to be a hundred. And the way he read, it was as though he was praying.” Uncle Grisha then asked if Brodsky was a believer, and was undeterred by the indifferent replies. “Naw, he ain’t a simple person. But he’s gotta believe because God made him special and blessed him with thoughts. It seems to me, He gave him a mission to preach His thoughts. If only he doesn’t take the wrong path.”

A contrary p.o.v.: Ludmila Shtern recalled in her memoir an uneducated peasant, “Uncle Grisha,” who was listening to a very young Brodsky read one night at her Leningrad home, crossing himself repeatedly during the reading. “I don’t understand poetry. I’ve only had four years of school. But the issue isn’t the poetry, it’s the thoughts,” he explained, “your Joseph spoke so many thoughts last night, most of them wouldn’t have even occurred to another person even if they lived to be a hundred. And the way he read, it was as though he was praying.” Uncle Grisha then asked if Brodsky was a believer, and was undeterred by the indifferent replies. “Naw, he ain’t a simple person. But he’s gotta believe because God made him special and blessed him with thoughts. It seems to me, He gave him a mission to preach His thoughts. If only he doesn’t take the wrong path.”

Stephens cites this marvelous passage from Watermark, describing another Sunday morning, this one in Venice during the unfashionable winter season, and yes, the rhythm of the prose zaps you into its orbit:

In winter you wake up in this city, especially on Sundays, to the chiming of its innumerable bells, as though behind your gauze curtains a gigantic china teaset were vibrating on a silver tray in the pearl-gray sky. You fling the window open and the room is instantly flooded with this outer, peal-laden haze, which is part damp oxygen, part coffee and prayers.