A chevalier moderne: Cécile Alduy raised to glory!

Saturday, December 9th, 2017

An intimate winter gathering at the home of the French consul. (Photo: Anaïs Saint-Jude)

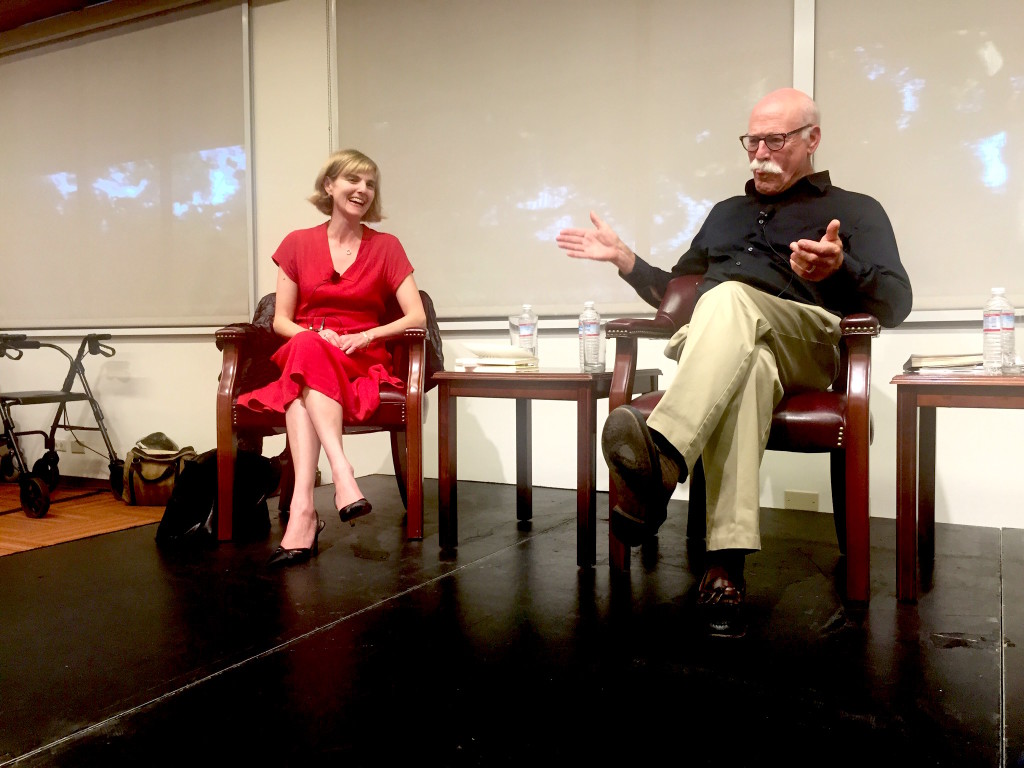

On Thursday night, Cécile Alduy was raised to glory (we’ve written about her here and here). She was admitted to what the French Consul Emmanuel Lebrun-Damiens called “one of the most select clubs on earth.” Its ranks include René Girard, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Salman Rushdie, Peter Brook, Jeanne Moreau, and many others – and more recently, Stanford’s Robert Pogue Harrison (we wrote about the occasion here) and Marie-Pierre Ulloa. In short, at the San Francisco hilltop home of the French consul general, Cécile became the most recent “Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres,” one of the highest cultural honors France offers.

Consul General Emmanuel Lebrun-Damiens, Cécile Alduy, and cultural attaché Juliette Donadieu (Photo: Anaïs Saint-Jude)

Lebrun-Damiens noted that the order was created in 1957, and strongly supported by André Malraux when General de Gaulle created a Ministry of Culture for France in 1959. Then he praised Cécile.

“At the core of your work, you specialized in analyzing and deconstructing the notion and origins of the myth of national identity,” he told her. “You have used your exceptional artistic, aesthetic, and analytical sensitivity towards expanding artistic, political, and cultural horizons.”

“As a young researcher at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, you decided to dedicate your thesis to great Renaissance French poets and to study how they shaped the notion of national identity through their creative writing. Following that path, you eventually exceeded your original academic discipline – literature – and shifted towards contemporary political analysis, with a particular interest for the ideology and rhetoric of the French extreme right,” he continued, acknowledging her articles in The Atlantic, The Nation, The New York Times, Le Monde, and others.

Cécile’s children also attended the celebration, and gamboled with a few others in the room where she received the small green-and0white striped ribbon and medal. Their participation was fitting and significant: it highlighted the theme of generations that informed both her remarks and those of the General Consul: Lebrun-Damiens noted the role of both her grandmothers. Her paternal grandmother, Jacqueline Alduy, was the mayor of a little town Amelie-les-Bains in the Pyrénées-Orientales, holding the office for 42 years until age 77. “As a woman of convictions, she was especially proud of your work on the extreme right and the analysis of Jean Marie and Marine Le Pen’s discourse,” he added.

Her maternal grandmother figured not only in his remarks, but in hers. Excerpt below:

Three Stanford chevaliers: Marie-Pierre Ulloa, Robert Harrison, Cécile Alduy. (Photo: Anaïs Saint-Jude)

My first thoughts go to those who instilled in me the sense that literature matters, that beauty matters, that the arts matter, more maybe than anything else. That they are not just the salt of life, a little extra spice or pastime, but rather the soul of the human experience, what makes us uniquely, truly human, what keeps us alive, that by which we might be redeemed as a species, and as individuals.

You named already some of the benevolent figures who imparted on me a love for words: my maternal grand-mother, Madeleine Daumas, a bookseller at one point, a typist who copy-edited the numerous books of her husband, but mostly an avid, yet quiet, composed reader. She read and re-read start to finish all the works by Racine, Montaigne, Balzac, Stendhal, Perec, Butor, Claude Simon, Steinbeck, Nabokov, Faulkner, Julien Greene, Kundera, Philippe Labro, Sollers, Yourcenar, de Beauvoir, John Le Carré, Simenon, Michel Serre. Each Christmas, we counted not the gifts, but the number of pages to read she had received. She was the first to read my first poems, short stories, essays, thesis… (and knowing she was made me pay scrupulous attention to spelling) …

In her family, her parents made “arts and literature and cinema the normal thing we do as a family, like going outdoors or watching the news. Yes, I have to admit that I was not always a happy camper after hours walking through the Pompidou museum staring at contemporary art installations, or visiting Greek ruins under a 110 degrees sun in the Summer. But thanks to them I learnt how to see: colors, and light and shadows; I learnt the shape and tastes of cultures close and far.”

An added bonus: the tree…

Then she spoke of the mission of the chevalier: “enriching French culture is not a matter of celebrating ‘roots’ and ‘land’ as the nationalist rhetoric goes, that culture defies borders and fructifies anywhere, everywhere, that arts and letters and the values they embody not only travel but flourishes by contact, migration, pollination.”

“If anything, this medal and this city rewards the work of bridging, of crossing boundaries (national boundaries but also the boundaries of academic disciplines and methodologies), of traveling across cultures and languages, of being on the move and in several places and cultures at once.

“At a time when borders and walls are erected, I am extremely proud to declare myself a migrant, an immigrant, a bi-national, and a citizen of the world.”

It was, she said, not an achievement as much as a beginning: “a peaceful military draft of sorts, a call to arms to resist the spoliation of our common right to a world where words mean what they say, where principles apply, where cultures are respected and humanistic values upheld.”

…and the flowers

“Being called to become a Knight in the Order of Arts and Letters is less a recognition of past works than an invitation, a request really, to fight for the arts and literature: it’s a call to arms to defend with the means of sharp thinking, and eloquence, and sensitivity, and aesthetic form the value of artistic creation, which is another word for the work of being human.”

With the beautiful decorations for holidays, there was plenty to please everyone. Only one expressed mild disappointment. Her four-year-old daughter asked a thoughtful question: if her mother was now a chevalier – where was her sword?

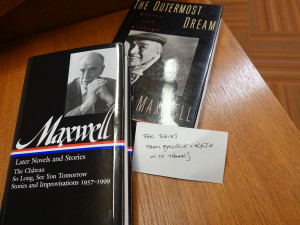

All in all, it was a wonderful send-off for Toby’s retirement – we presented him with a signed first edition of the late William Maxwell’s The Outermost Dream, a collection of his essays from The New Yorker – fitting, because Toby himself is a regular contributor to the magazine.

All in all, it was a wonderful send-off for Toby’s retirement – we presented him with a signed first edition of the late William Maxwell’s The Outermost Dream, a collection of his essays from The New Yorker – fitting, because Toby himself is a regular contributor to the magazine.

With the publication of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus in the same year, Camus became a public figure and an existential legend, though he eschewed the link with

With the publication of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus in the same year, Camus became a public figure and an existential legend, though he eschewed the link with