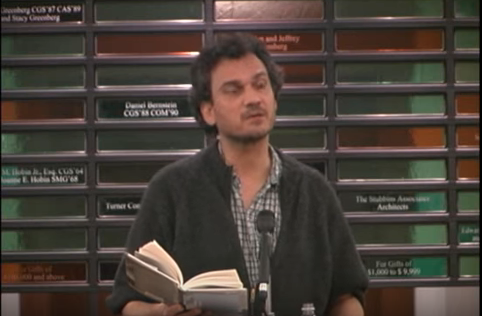

A talker (Photo courtesy Knopf)

My goodness. Does this man ever have a bad interview? Like him or hate him, agree with him or not, Martin Amis is always fascinating, incisive, opinionated, controversial. The current Q&A at The Los Angeles Review of Books is proof.

“Despite the variety of subjects, the guiding theme of most of these pieces is the impact of time on talent and the rarity of a long, multichaptered literary career,” said interviewer Scott Timberg.

The Book Haven was greedy and wanted to quote everything, but we calmed down and settled for two excerpts. The first discusses poet Philip Larkin‘s appeal for novelists. A timely topic, because Stanford’s Another Look book club recently featured Larkin’s little-known novel, A Girl in Winter:

Timberg: You have a great line on Larkin in one of your essays, where you say he’s not exactly a poet’s poet — he’s too widely embraced for that — but a novelist’s poet. Tell me what you mean by that.

Martin Amis: Well, it was suggested to me by the poet-novelist Nick Laird. We were talking about Zadie [Smith, Laird’s wife] loving Larkin, and Nick said, “All novelists love Larkin.” That resonated for me, and when I came to write that piece I saw just how true it was — that he belongs with the novelists rather than the other poets. “A poet’s poet” is usually very much in danger of being precious, or exquisitely technical. Larkin is technically amazing, but he doesn’t draw attention to it. It’s his character observation and phrase-making that put him in the camp of the novelists, I think.

A grasp of ordinary people

There’s something oddly visual about Larkin too, for someone who squinted his life away through thick glasses. I feel like I can see those poems, the curtains parting and the little village and the ships on the dock.

Yes — and very thickly peopled. He has a grasp of ordinary character — which is very hard to get. The strangeness of ordinary people.

That may be why people who don’t read a lot of poetry respond to Larkin, if they read him at all. It’s like Auden. You might not understand everything in those guys’ work, but you get something out of it if you try.

Yes — though Auden is a lot more difficult. And a greater poet, I think, in the end. But — yes — Larkin doesn’t need much interpretation from critics in the way other poets do.

The authors you write about in your book are mostly novelists. Do you read much poetry, contemporary or otherwise?

Yeah, I do. It’s much harder to read poetry when you’re living in a city, in the accelerated atmosphere of history moving at a new rate. Which we all experience up to a point. What poetry does is stop the clock, and examine certain epiphanies, certain revelations — and life might be moving too swiftly for that.

He reads “The Greats.”

But I still do read, not so much contemporaries, as the canon. I was reading Milton yesterday, and last week Shakespeare — it’s the basic greats that I read.

It’s amazing how much poetry dropped out of the literary conversation in the States over the last few decades. It’s not gone entirely, but it doesn’t show up very much. I find British and Irish people, especially those born in the 1940s and ’50s, much more engaged with verse. It’s really changed over time.

It really has, and also the huge figures are no longer there, in poetry. Lowell, Seamus Heaney was one of the last. And I’m convinced, for that reason, that we live in the age of acceleration. Novels have evolved to deal with that, as the novel is able to do — just by moving a bit faster. Not being so speculative, digressive, intellectual. But poetry moves at its own pace, I think — and you can’t speed that up.

***

Your book is about the effect of time on talent — you take the long view on Nabokov and others. Each career is different, but did you perceive any patterns in the way these things go? Bellow, Nabokov, Roth — they all had robust careers. But we could contrast those with shorter or less successful ones — Joseph Heller, maybe, or Alex Chilton. Musicians, artists, writers who seemed exciting at first, but didn’t really keep up.

Indefatigable Nabokov

You get a sense reading a novel sometimes that this novelist has a big tank. A huge reserve. And some people don’t — and they exhaust it quite quickly. You can watch that process in any artist, I think. They arrive fresh, and then they use up, sometimes, their originality, and then are reduced to rephrasing that. You only see it fully when they’re coming to the end of their careers; then you can assess the size of that tank.

But you do go from saying hi, when you arrive on the scene, to saying bye, making your exit. Medical science has given us the spectacle of the doddering novelist. As I say in the first of the Nabokov essays, all of the great novelists are dead by the time they reach my age [68]. It’s a completely new phenomenon, and it’s a dubious blessing. Novelists probably do go on longer than they ought to, now.

Philip Roth has done the dignified thing, just quit. I know others who’ve done that. It seems to me that rather than gouging out another not-very-original book, you should just step aside.

Sometimes it’s easy to tell, but sometimes it’s harder. If we were reading, back in the 1960s, Goodbye, Columbus alongside Catch-22, would we have been able to tell which of the careers would last six decades and which would peak right out of the gate?

Catch-22? Embarrassing.

It’s hard to predict. But again, you do get an idea of the size of the reserves. Writers who start late sometimes go on longer, because the tank stays full longer.

My father and I used to disagree about Catch-22. He thought it was crap. He used to say of me that I was a leaf in the wind of trend and fashion.

Every father says that about his son!

I think you have to be suspicious of any instant cult book. See how it does a couple of generations on.

I looked at Catch-22 not long ago and I was greatly embarrassed — I thought it was very labored. I asked Heller when I interviewed him if he had used a thesaurus. He said, “Oh yes, I used a thesaurus a very great deal.” And I use a thesaurus a lot too, but not looking for a fancy word for “big.” I use it so I can vary the rhythm of what I’m writing — I want a synonym that’s three syllables, or one syllable. It’s a terrific aid to euphony, and everybody has their own idea of euphony. But the idea of plucking an obscure word out of a thesaurus is frivolous, I think.

Read the whole thing here.