A fierce poem from a feverish bed. (Photo courtesy the Ward family)

In his brief life, Matthew Ward translated works by Colette, Jean Giraudoux, and Roland Barthes into English – but his favorite project was Albert Camus’s The Stranger. His celebrated “American” translation of the classic earned him a PEN award in 1989, as well as critical acclaim.

In a sense, the translation was born at Stanford, where Ward learned French and fell in love with France during his stay in Tours as part of Stanford’s Overseas Studies program in 1971 (he earned his B.A. From Stanford in 1973). Clearly, Ward’s translation of The Stranger is a perfect choice for the “Another Look” book club discussion at 7:30 p.m., Monday, June 1, at the Stanford Humanities Center – and not only for aesthetic reasons. It represents a sort of homecoming.

If Ward’s Stanford roots are not widely recognized, part of the reason may be that he was known in those days as “Gary,” an energetic, gregarious presence who was very, very smart. “He had an immense intellectual hunger,” recalled Stanford English Prof. John Bender, who was the faculty advisor in Tours the year Ward attended, and recalled the poet and translator’s “eagerness and sparkle.”

“He wanted to know everything, whatever he could know.” Most of all, recalled Bender, “he was passionately interested in French.”

During the six-month sojourn in Tours, Ward also forged an important friendship with Monika Greenleaf, now an associate professor of Slavic literature at Stanford, but then a “scholarship kid” as he was. “I have an intense memory of his face and body when he became enthused about something: his big brown eyes would glow, then a huge mocking grin and demonic chuckle, and a flurry of gestures. It was always a manifesto about literary style, freedom, religion, young men’s conquests of their world, and above all, Joyce” – and, she quickly added, Kerouac, Hemingway, Ginzburg, Camus, and Proust, too.

“He and I bonded above all in our mutual and rivalrous pursuit of le mot juste,” she said. “Being Irish, he had the scintillating verbal gift that comes with the territory.”

Irish was only half the story. He grew up as one of nine children in a Spanish-speaking, working-class family in Denver. ”I internalized Romance languages listening to my mother,” he told The New York Times. ”Our family goes back to 1598 in old New Mexico, with a governor as an ancestor. And I really do have a mother named Carmen.”

Greenleaf remembers the Stanford students taking a night train to Spain during the running of the bulls at Pamplona, “standing the whole way talking – about Hemingway, of course – and drinking.”

“We were so hung over the next morning that we climbed trees to watch the spectacle and ended up falling asleep among the branches.” Ward and a friend, however, “took off down the street in front of the bulls.” The kids had little money, and lived on potato omelettes, wine, and cioccolate calliente. Traveling to the Basque city of San Sebastián, “we got off the train and ran straight into the ocean waves to wash off. That town and its churches perched on the edge of the ocean seemed like a paradise to us.”

When the sun went down, Ward would entertain them with his stories and his poems: “He always had a diary with him and filled it with extravagant Joycean sketches, which he would read to us at night. We all liked to catch glimpses of ourselves in the textures he created. He was constantly practicing to become a writer,” she said.

At the party to celebrate the end of their stay in Tours, Ann Bender recalls swing-dancing with Ward. He was the only student who knew the dance steps of the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s. “He was very much a people person,” she said, despite the usual writer’s life of solitude and thought.

Back in Palo Alto, Ward rented a cottage behind the home of English Prof. William Chace, who remembers him fondly as a great conversationalist and immensely smart. Ward received an acknowledgement in Chace’s The Political Identities of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot. “I think he helped me just talking about the topics,” he recalled. “What did Gary contribute? Friendship and good humor.”

After Stanford, Ward went for advanced degrees in Anglo-Irish literature at University College in Dublin and at Columbia University; Chace left Stanford to become president of Wesleyan and later Emory University. “He wrote us to say he had become involved in the atelier of Richard Howard, translator of great things,” recalled Chace, and that he had taken a pen name, too. Ward told his mother he was dropping “Gary” for his confirmation name,“Matthew.” It had more of an authorial ring to it, he told her.

Hardscrabble life of a translator

The breakthrough moment came when Judith Jones, the legendary editor at Knopf who had worked with John Updike, Anne Tyler, John Hersey, Elizabeth Bowen, and William Maxwell, felt that a new translation of Camus was needed, one that was closer to the spirit of the author than the 1946 translation by the highly respected translator Stuart Gilbert, which was faulted for its British flavor. (One example: “You’ve knocked around the world a bit, and I daresay you can help me.”)

”I jumped at the chance and worked with Judith on it for nearly three years,” said Ward. “It gave me an opportunity to push my one grain of sand up the beach of culture.”

“I jumped at the chance.”

The dramatically new translation was praised by The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, and others. Ward told The New York Times, “what I’ve done is closer to the author’s intent, and that’s what counts.”

“Camus admitted using an ‘American method,’ particularly in the first half of the book,” Ward said. “He mentioned Hemingway, Dos Passos, Faulkner and James M. Cain as influences. My feeling is that The Stranger is more like Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice than Camus cared to admit.”

By that time, Ward was living in a fourth floor walk-up in Manhattan. Bender recalls his visit to Stanford, where they talked about translation and the hardscrabble life of a translator. “He had lived a life without a lot of material rewards in it, and yet he did extraordinary translations,” said Bender. “All this acclaim, but it paid almost nothing.”

Greenleaf, by then at Stanford, also remembered a reunion about the same time in the 1980s. “We talked our heads off, as of old, and toward the end he read me excerpts of a narrative poem in progress, called, I believe, ‘The North.’ It was thrilling to recognize his mature talent. He sent me a paper copy, but I lost it during one of my moves, and I don’t know if it was published.

“He let me know when his translation of The Stranger won its prize, and we were sure that this was the beginning of his writerly renown. I found out about his infection with AIDS through a fierce poem he sent me from his feverish, sore-ridden body and still incandescent mind, not at all resigned. I cried hot tears reading it.”

Ward died on June 23, 1990, at the age of 39. A memorial evening to celebrate his life was organized in Greenwich Village. Chace and his wife drove to the event from their Connecticut home, with plans to return afterwards. As the clock was moving closer to midnight, Chace asked the playwright and gay rights activist Larry Kramer when the formal remarks would begin. Kramer looked back at him with surprise. “What do you mean? I go to these every night,” he replied. As the AIDS crisis swept through the city, formal memorials had been abandoned – the strain would have been unbearable, he explained. No one had the energy anymore.

Twenty-five years’ distance makes any strain bearable, but it doesn’t fill the missing chair or put the subtracted voice back into the conversation. Ward left his traces in many of the pitch-perfect intuitions that informed his translation of The Stranger, fulfilling his wish that his work “would bring a new generation to the great Camus novel.”

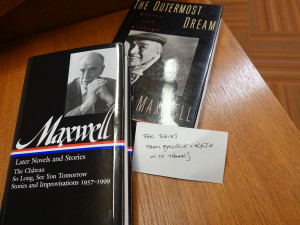

All in all, it was a wonderful send-off for Toby’s retirement – we presented him with a signed first edition of the late William Maxwell’s The Outermost Dream, a collection of his essays from The New Yorker – fitting, because Toby himself is a regular contributor to the magazine.

All in all, it was a wonderful send-off for Toby’s retirement – we presented him with a signed first edition of the late William Maxwell’s The Outermost Dream, a collection of his essays from The New Yorker – fitting, because Toby himself is a regular contributor to the magazine.

With the publication of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus in the same year, Camus became a public figure and an existential legend, though he eschewed the link with

With the publication of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus in the same year, Camus became a public figure and an existential legend, though he eschewed the link with