“Mass and class” for the book industry? Says Steve Wasserman: “I’d go for class every time.”

Thursday, April 8th, 2021

Six years ago we wrote about Berkeley publisher Steve Wasserman of Heyday Books and his suggestions for the Eros of Difficulty. Here is an addendum, in his own words:

When I ran the Los Angeles Times Book Review (1996-2005) I was temperamentally allergic to the notion, widespread in the newsroom, that the paper must reflect the alleged interests of its readers.

That notion, in the digital age, has now achieved a kind of hegemony. It’s the metric that rules. The underlying presumption is that the paper (or now website) must act as a “mirror” reflecting readers’ “interests,” otherwise the paper risked being “out of touch.” Only in this way, it was argued, could the bond between readers and the paper be strengthened. I thought then – and think now – this was exactly wrong. Rather, a better analogy would be the telescope, which when looked through one end makes near things appear distant, thus throwing them into sharp relief and providing a useful and unsuspected perspective. Or, alternatively, turned around and looked through at the other end makes faraway things appear closer, thus giving us an opportunity to see afresh things that otherwise might escape our attention. I felt it was important to spurn the faux populism of the marketplace. I sought to honor what Mary Lou Williams, the jazz pianist and composer, said about her obligation to her audience and her art: “I … keep a little ahead of them, like a mirror that shows what will happen next.”

I wanted to give readers the news that stays news. Of course, ideally I wanted what Otis Chandler in his heyday had wanted: mass and class. But if it came down to a choice between the two, I knew I’d go for class every time. In literary affairs, I was always a closet Leninist: Better fewer, but better. Today, my friend, the brilliant and resourceful Rochelle Gurstein, sent me a lovely quote from Ernst Gombrich (writing in his 1969 essay “Art and Self-Transcendence”), which had I known it, I would have emblazoned it on the door to my office: “This parrot cry of relevance seems to me total nonsense. … The egocentric provincialism of people who so lack the capacity for self-transcendence that they can only listen to what touches their own individual problems threatens us with such intellectual impoverishment that we must resist at all costs.”

Some weeks ago, Rochelle had plucked from Joshua Reynolds‘s farewell discourses on art, this gem. Reynolds, taking his leave from the Academy of Art he’d founded, surprised his audience (and later readers, as Rochelle wrote to me) by offering Michelangelo as the greatest artist and the one students ought to take as their exemplar over Raphael whose virtues he had been at pains to praise in the preceding fourteen lectures. Now, Reynolds tells his audience, “We are on no account to expect that fine things should descend to us; our taste, if possible, must be made to ascend to them.” Against those who believe they can trust their first impressions, Reynolds insists, “As [Michelangelo’s] great style itself is artificial in the highest degree, it presupposes in the spectator, a cultivated and prepared artificial state of mind. It is an absurdity therefore to suppose that we are born with this taste, though we are with the seeds of it, which, by the heat and kindly influence of his genius, may be ripened in us.”

There really wasn’t a winner … or rather, there were only winners. The annual “A Company of Authors,” which we previewed

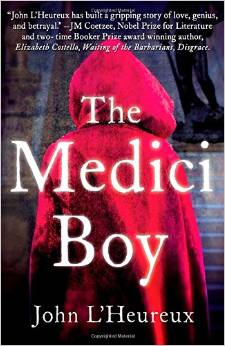

There really wasn’t a winner … or rather, there were only winners. The annual “A Company of Authors,” which we previewed  “Way back in 1999 on my first trip to Florence I had the good fortune to visit the Accademia and the Bargello on the same day, which meant I got to see Michelangelo‘s David in the morning and Donatello’s David in the afternoon. They provided me with a good close-up contrast. I was astonished at the Michelangelo – it’s vast and overwhelming – and I was embarrassed by the Donatello. I didn’t know where to look. The statue is so unashamedly naked. And erotic, with an eroticism that is quite calculated, I think. It asks to be looked at. It asks to be touched. I knew absolutely nothing about Donatello at that time, but one look at the David convinced me that Donatello knew exactly what he was doing and went ahead and did it anyway. …

“Way back in 1999 on my first trip to Florence I had the good fortune to visit the Accademia and the Bargello on the same day, which meant I got to see Michelangelo‘s David in the morning and Donatello’s David in the afternoon. They provided me with a good close-up contrast. I was astonished at the Michelangelo – it’s vast and overwhelming – and I was embarrassed by the Donatello. I didn’t know where to look. The statue is so unashamedly naked. And erotic, with an eroticism that is quite calculated, I think. It asks to be looked at. It asks to be touched. I knew absolutely nothing about Donatello at that time, but one look at the David convinced me that Donatello knew exactly what he was doing and went ahead and did it anyway. … Truth be told, I have the same misgivings, that at my death my survivors will find only piles and piles of confused and disorganized papers and notes. So I was relieved that the bookstore also carried a few books by some of the panel moderators at “A Company of Authors” – and Humble Moi was among them. So at least one series of efforts will not be entirely lost to time. The featured book was one of my earlier efforts,

Truth be told, I have the same misgivings, that at my death my survivors will find only piles and piles of confused and disorganized papers and notes. So I was relieved that the bookstore also carried a few books by some of the panel moderators at “A Company of Authors” – and Humble Moi was among them. So at least one series of efforts will not be entirely lost to time. The featured book was one of my earlier efforts,