Running a blog ain’t easy. It’s time-consuming, it exposes you to nasty comments, and it pays (for most of us) diddly squat. So it’s nice when a blog gets kudos and sometimes, even a little cash. My friend Abbas Raza started 3QuarksDaily a dozen years ago … well, actually, our friendship began on 3QD, though I have yet to visit him in his idyllic village in the Italian Alps, where I will be able to sample some of his exquisite North Indian and Pakistani cooking.

Abbas Raza & poet Robert Pinsky – wife Margit Oberrauch looks on.

That will be a future pleasure. The past pleasure is that Humble Moi and the Book Haven have been regularly featured on 3QD, just as we’ve regularly featured 3QD gleanings on our pages. We’ve always been pleased as punch about it, but we must say that it’s been taken to a new level with Thomas Manuel‘s article, “Why the Web Needs the Little Miracle of 3QuarksDaily,” in The Wire today:

The need for filters, aggregators and curators to navigate the web isn’t new. Arts and Letters Daily, the inspiration for 3QD, was founded by the late Denis Dutton way back in 1998. It in turn was inspired by the news aggregator, Drudge Report, which started in 1995. But each of these had their own niche (literary humanities and conservative politics respectively) while Raza envisioned something more all-embracing – which ironically turned out to be a niche of its own. His plan was to “collect only serious articles of intellectual interest from all over the web but never include merely amusing pieces, clickbait, or even the news of the day… to find and post deeper analysis… and explore the world of ideas… [to] cover all intellectual fields that might be of interest to a well-educated academic all-rounder without being afraid of difficult material… [and to] have an inclusive attitude about what is interesting and important and an international outlook, avoiding America-centrism in particular.”

Morgan Meis is proud, too.

In practice, this elaborate vision looks deceptively simple. According to Morgan Meis, one of the editors of 3QD, all you had to do was “get a few reasonably smart people together, have them create links to the sorts of things they would want to read across the web, on any given day. Voila! You’ve got an interesting website. Then, don’t fuck that simple formula up. Don’t get cute. Stay the course.”

As Raza figured, an editorial team of ‘reasonably smart people’, by dint of their own diverse interests, would automatically bestow the site with a broader perspective. Currently this team, apart from Raza and Meis, consists of Raza’s old friend, Robin Varghese, his two sisters, Azra and Sughra Raza, poetry editor, Jim Culleny and assistant editor, Zujaja Tauqeer.

Varghese and Raza met at Columbia University in 1995 while they were both graduate students. Varghese, who posts much of the political content on 3QD, was pursuing a doctorate in political science while Raza had taken up philosophy after studying engineering as an undergraduate. Varghese still lives in New York and works in the development space while Raza currently lives with his wife in Brixen, a small town in the Italian Alps, where his major occupation, apart from running the website, is cooking elaborate North Indian and Pakistani style meals.

The article has a nice overview of the current predicament of the cyberspace echo chamber, and how 3QD really is different:

Today, information discovery comes in all shapes and sizes – from the New Yorker Minute that does a number on theNew Yorker, to Amazon’s book recommendation behemoth. There isn’t a doubt that the latter is a remarkable feat of software engineering, as are the algorithms employed by Netflix, Spotify, Facebook and Google. Netizens depend on these wonders – relying on them to suck in chaos and spit out order.

Hobbies.

Yet these same sites are also examples of total moral capitulation. Underlying the logic of many algorithms is the idea that to find what people want, we need only look for what similar people have wanted. Apart from engendering near total surveillance, a mechanism built around the urgency of giving people what they want ignores the importance (or even the existence) of a responsibility to give people what they might need. This isn’t a surprising stance for profit-driven corporations to take. However, as citizens who value democratic access to resources and knowledge, it’s dangerous to allow ourselves to become complacent with gatekeepers who don’t acknowledge their own roles as stewards or see their power as weighted by responsibility to the community. It’s the logic of giving people what they want that’s made virality the metric for deciding what makes the news and triggered the current race for the bottom that has marked the new culture wars.

In stark contrast stands the purpose of 3QD as outlined by Raza in a radio interview with the National Endowment for the Arts. Laying out the three classical realms of knowledge – the realm of beauty, the realm of morality, the realm of truth, he stressed that all three were “immensely important to all human beings”. It’s a safe assumption that he didn’t learn this through a market survey.

What’s their secret? According to Morgan Meis, another 3QD friend: “It is the people and the relationships,” he said. “That’s the core of it. It is, to be terribly corny, love that has always held the thing together.”

Read the whole thing here. And go to 3QuarksDaily here.

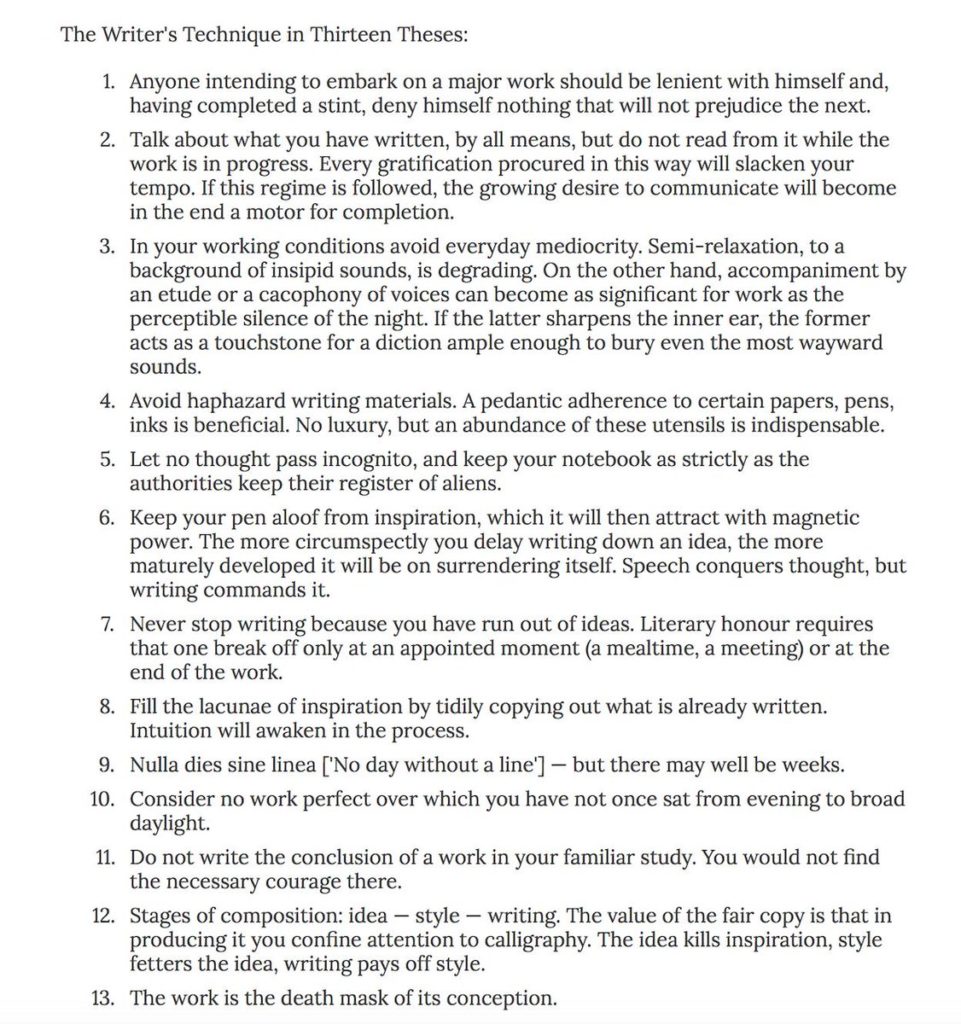

“The Writer’s Technique in Thirteen Theses” is part of his 1928 treatise One-Way Street, one of only two books published in his lifetime. This 13 tips were posted on Twitter recently and I thought I’d share them. It reminded one tweeter of a sign that read: “The worst words you ever write are far better than the best words you never write.” Another remembered an old, established writer I heard on NPR back in the 1980s: “Write through your mediocrity. Keep writing… right on through it.”

“The Writer’s Technique in Thirteen Theses” is part of his 1928 treatise One-Way Street, one of only two books published in his lifetime. This 13 tips were posted on Twitter recently and I thought I’d share them. It reminded one tweeter of a sign that read: “The worst words you ever write are far better than the best words you never write.” Another remembered an old, established writer I heard on NPR back in the 1980s: “Write through your mediocrity. Keep writing… right on through it.”

“Why should we celebrate these dead men more than the dying?”

“Why should we celebrate these dead men more than the dying?”