Is evil really banal? Why Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem shocked the world.

Thursday, March 8th, 2018

Both sides now.

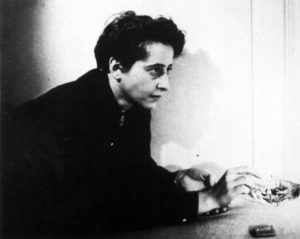

In 2012, I eagerly, perhaps a bit worshipfully, attended Margarethe von Trotta‘s acclaimed film, Hannah Arendt, describing how the heroic philosopher came to be at the 1961 Jerusalem trial of the notorious Nazi Adolf Eichmann. As everyone knows now, the German-Jewish thinker found no monstrous incarnation of evil, but rather a banal bureaucrat following orders. And so she fell out with Jewish leaders, Israelis, much of New York’s intelligentsia, and writers like Saul Bellow, too.

Now I have a better idea of the other side, after reading Harvard Professor Ruth R. Wisse‘s”The Enduring Outrage of Hannah Arendt’s ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’: Fifty-five years later, her book still has the power to shock—and disgust.” It was one of the thousand tabs on my browser, waiting to be read (in this case, waiting for three weeks), in another publication I rarely read, Commentary. (I’m a sucker for anything on Arendt – read her moving discussion of refugees here.)

The background: The international military tribunal in Nuremberg did not focus on the Jews, in part because Eichmann had never been caught. He had fled to Argentina with his family. According to Wisse, “It is now known that the Germans and the CIA were aware of Eichmann’s whereabouts and never acted on their information. When Fritz Bauer, a member of the German investigative commission, realized that his superiors were contriving not to go after Eichmann, he got the information to the Israelis, who captured him in Argentina and flew him to Jerusalem.”

Wisse continues: “The trial itself was without precedent or parallel. The Israeli poet Natan Alterman wrote that it ‘would fill an eerie void that has been hidden somewhere in the soul of the Jewish people, in the history of its lives and deaths, ever since it went into exile.’ The void he referred to could not have been filled previously because the Jews had never been in a position to prosecute their murderers. Now they were. Given that this was the first and, as seemed likely, the only time that Jewish survivors would be able to confront one of the individuals responsible for the murder of their relatives, the event assumed outsized importance.”

Wisse continues: “The trial itself was without precedent or parallel. The Israeli poet Natan Alterman wrote that it ‘would fill an eerie void that has been hidden somewhere in the soul of the Jewish people, in the history of its lives and deaths, ever since it went into exile.’ The void he referred to could not have been filled previously because the Jews had never been in a position to prosecute their murderers. Now they were. Given that this was the first and, as seemed likely, the only time that Jewish survivors would be able to confront one of the individuals responsible for the murder of their relatives, the event assumed outsized importance.”

“When it became known that Hannah Arendt would be covering the trial for the New Yorker, there was great anticipation. ‘A foolproof choice,’ wrote Marie Syrkin, one of American Jewry’s leading intellectuals. ‘Who better qualified to report on the trial in depth than Hannah Arendt, scholar, student of totalitarianism and of the human condition, and herself a German Jewish refugee who came to the United States after the rise of Hitler?’ wrote Wisse. “Indeed, of all the German refugees who had been admitted to America just before or at the start of the war, none was better known or more widely admired than Arendt, who had been accepted by the New York intelligentsia not merely as one of their own, but as prima inter pares. Hence the shock when her articles appeared in February and March 1963 and then in the expanded book later that year. Rather than report on the trial as a journalist or observer, Arendt used it as an occasion to expand her theory about totalitarianism—the subject of her most ambitious book.”

Enter Israeli poet Haim Gouri, who published daily dispatches in a left-labor newspaper, later published as, Facing the Glass Booth.

Enter Israeli poet Haim Gouri, who published daily dispatches in a left-labor newspaper, later published as, Facing the Glass Booth.

Like Arendt, Gouri is struck by the contrast between Eichmann’s apparent impassivity and the evils he is known to have committed, and, like her, he too later becomes agitated when the witnesses for the prosecution describe Jews herded to their death “like sheep to the slaughter.” But the report tracks his evolution. “Like everyone else present, I felt close to the line separating sanity from madness, but in my case it was for the first time,” he writes. “I felt I was beginning to comprehend the incomprehensible, however wide the gulf separating me from those who were there for even a single day.” Gouri is humbled as he follows the proceedings: “[We] who were outside that circle of death have forgiveness to ask of the numberless dead whom we have judged in our hearts without asking ourselves what right we have.” To state only the obvious, Gouri came to gain understanding, Arendt to impose her understanding on the trial. Gouri’s account follows the sequence of developments. Arendt surmises, synthesizes, and summarizes.”

Gouri was writing for a Jewish readership in a Jewish language in a Jewish country, Arendt for the New Yorker. She did her research relating to the trial in Germany and most of the writing as a research scholar at Wellesley College. In her book on the Eichmann trial, the historian Deborah Lipstadt points out that Arendt left Jerusalem on May 10 and missed five weeks of witness testimony; she was also absent for the prosecution’s cross-examination when Eichmann was at his sharpest.

In short, “The mass murderer who wanted to persuade the court that he was not the agent of his crimes found an ally in a philosopher who, to make her thesis work, needed to prove he lacked moral agency.”

It’s a controversial, passionately argued article. Whether you agree or disagree with Prof. Wisse, it’s worth a look here. Trailer of the movie below.