R.I.P. Daniel Weissbort, champion of translation everywhere

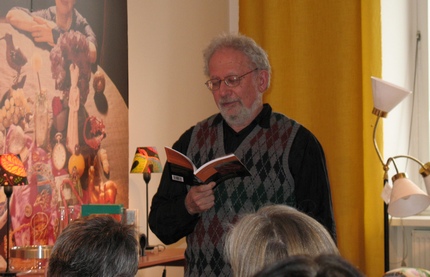

Tuesday, November 19th, 2013Daniel Weissbort is dead. I heard this yesterday from Neil Astley of Bloodaxe Books in the U.K., but hadn’t been able to confirm it till I found it posted here, on the website of the influential journal he founded with Ted Hughes in 1965, Modern Poetry in Translation. He continued to edit the magazine until 2003.

Perhaps the major obituaries are yet to come out, but it’s surprising how little a splash major figures in translation make in today’s world, although Weissbort was also a poet of note. I never met him face-to-face, but I know him from once remove; his wife, the Russian scholar Valentina Polukhina, is a colleague, friend and regular correspondent. He would have been 78 this year, and I know he has been ill for some years.

According to the website (which has a page for tributes here):

He was associated with MPT for nearly forty years, and he saw it through its birth as a “scrappy-looking thing – just to keep their spirits up…” (from a letter by Ted Hughes to Daniel Weissbort in 1965) to becoming a periodical of international importance and renown, which published some of the best international poets in the best translations. He was also a translator of poetry and a poet in his own right, and he made it his cause to get Russian poetry better known and better read in the English-speaking world, editing and translating Russian poetry tirelessly, and hosting and leading translation workshops. His most recent translations of the Russian poet Inna Lisnianskaya Far from Sodom were published to great acclaim by Arc Publications in 2005.

Nicholas Wroe, whose 2001 Guardian interview with Czesław Miłosz was included my volume Czesław Miłosz: Conversations, interviewed Weissbort in the same year. It was posted on a few Facebook pages:

Nicholas Wroe, whose 2001 Guardian interview with Czesław Miłosz was included my volume Czesław Miłosz: Conversations, interviewed Weissbort in the same year. It was posted on a few Facebook pages:

“Poetry happens everywhere,” writes Daniel Weissbort in the introduction to Mother Tongues, “but sometimes, often, it happens in languages that do not attract attention. We are the poorer for not experiencing it, at least to the extent it can be experienced in translation.”

Although he wasn’t conscious of it at the time, translation had been a part of this poet, editor and translator’s life from the outset. “My parents were Polish Jews who came to London from Belgium in the early 1930s,” Weissbort explains. “They spoke French at home because that was the language they met in, but I was so determined to be English that I’d always answer them in English.” …

It was Hughes’s idea to get as many literal translations of work as possible. “We didn’t want carefully worked, minute things that took forever to produce,” explains Weissbort. “It sounds a bit insensitive now, but we wanted quantity even if it was in quite rough-and-ready translation.” He says that at the moment one of the big debates in translation is between so called foreignisation and domestication. “Domestication looks like something that was first written in English,” explains Weissbort. “Post-colonial theory is very much in favour of foreignisation, seeing domestication as an imperialistic strategy that is opposed to allowing the foreignness to come into the language. I suppose we were foreignisers before it was invented.”‘

Weissbort is also due to publish his own, 11th collection of poems, Letters to Ted, written after Hughes’s death, as well as a memoir of Nobel prizewinner Joseph Brodsky. (Read the rest here.)

Weissbort is also due to publish his own, 11th collection of poems, Letters to Ted, written after Hughes’s death, as well as a memoir of Nobel prizewinner Joseph Brodsky. (Read the rest here.)

I reviewed the latter volume, From Russian with Love, in a Kenyon Review article called “Uncle Grisha Was Right” – it’s here. Being a Brodsky translator was a crushing, ego-deflating experience for many, and Weissbort was one of the earliest translators, before he could have taken courage from the tales of other casualties. Weissbort agonizes over the experience, analyzing and doubting himself – something the Russian Nobel laureate never did. As I wrote: “He [Brodsky] came from a culture that had bypassed Freud and his heirs, where an enemy was an enemy and not just a projection of an inner landscape. He was not, to put it mildly, a man crippled with a sense of his own contradictions. Hence, his attacks could be unambiguous and fierce. As sycophants multiplied exponentially, it became hard, some of his friends say, to tell him the truth—for example, the truth about his abilities to write English verse and translate into it.”

Yet in the end, Weissbort seemed to be unexpectedly buoyed by the experience, and came to a startling conclusion that says as much about the master translator as it does about the poet:

“At a commencement address years later, he [Brodsky] spoke of ‘those who will try to make life miserable for you,’ and added: ‘Above all, try to avoid telling stories about the unjust treatment you received at their hands; avoid it no matter how receptive your audience may be. Tales of this sort extend the existence of your antagonists. . . .’

“At a commencement address years later, he [Brodsky] spoke of ‘those who will try to make life miserable for you,’ and added: ‘Above all, try to avoid telling stories about the unjust treatment you received at their hands; avoid it no matter how receptive your audience may be. Tales of this sort extend the existence of your antagonists. . . .’

That’s the legacy of the man. But the poetry? Weissbort seesaws and perseverates for pages and pages, and there is much repetition and confusing back-and-forth in time … Yet despite the waffling and self-deprecation, he makes a central, remarkable contention: Weissbort argues that Brodsky ‘was trying to Russianize English, not respecting the genius of the English language, … he wanted the transfer between the languages to take place without drastic changes, this being achievable only if English itself was changed.’

In short, Weissbort invites us to listen to Brodsky’s poetry on its own terms. As he tells a workshop: ‘It’s like a new kind of music. You may not like it, may find it absurd, outrageous even, but admit, if only for the sake of argument, that this may be due to its unfamiliarity. Give it a chance, listen!’”