Was John Milton less dour than we imagine? He may have been a fun kind of guy.

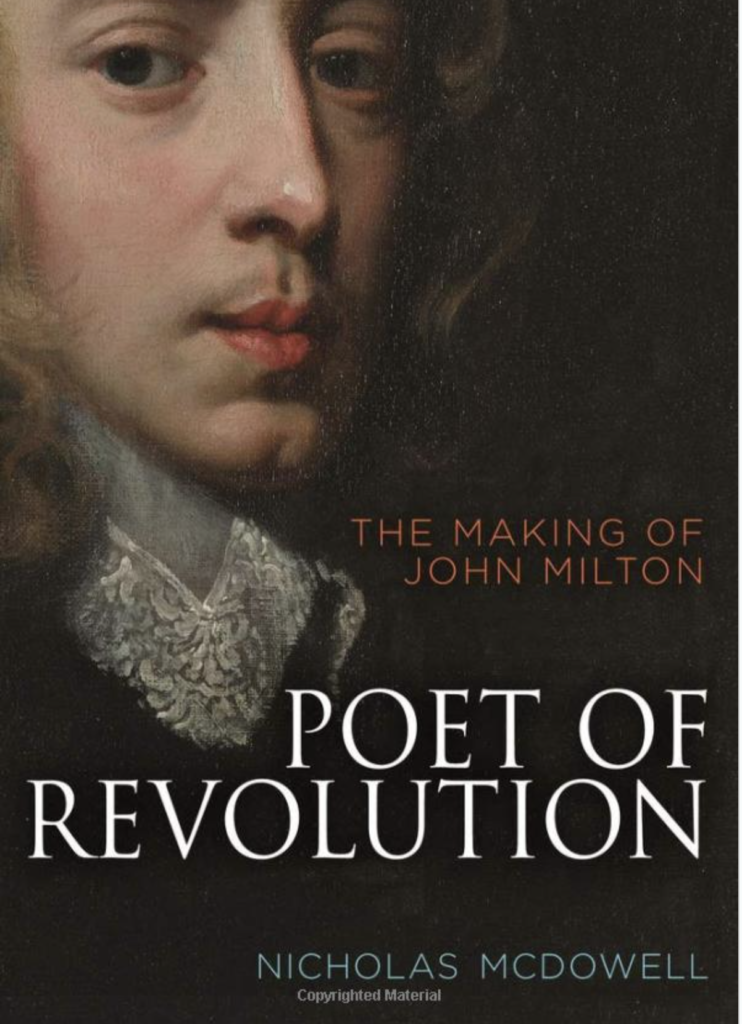

Wednesday, January 13th, 2021 Poet and translator A.M. Juster reviews Nicholas McDowell’s Poet of Revolution: The Making of John Milton in The Los Angeles Review of Books:

Poet and translator A.M. Juster reviews Nicholas McDowell’s Poet of Revolution: The Making of John Milton in The Los Angeles Review of Books:

As a young teenager, John Milton set out in a fiercely determined way to become not just a successful poet, but a poet the literary world would regard as a peer of Homer, Virgil, Dante, and Petrarch. He organized his life around this goal with a demanding plan that required close reading of a prodigious number of texts — an approach that would puzzle today’s burgeoning guild of poets, who too often spend a few years in MFA programs learning about erasure poetry, liminality, and their depressing professional prospects. Even before matriculating at the University of Cambridge at the age of 16, Milton wrestled with whether greatness required him to write in Latin or in English, and for many years his uncertainty about this question caused him to hedge his bets by writing in both languages. …

Nicholas McDowell’s erudite Poet of Revolution: The Making of John Milton helps us understand why and how Milton pursued poetic glory. He lays out in clear prose what we know of Milton’s family life and education, and he describes in detail the intense curricula at St Paul’s School and the University of Cambridge, which focused on fluency in languages, both modern and ancient, along with critical approaches to literature, history, theology, and other disciplines. He also shows us that Milton’s teachers and professors were adamant that the lives of Virgil, Dante, and Petrarch demonstrated that wide and deep reading in the humanist canon is a necessary precondition for success as a true poet.

McDowell’s judicious weighing of the historical evidence relating to the young Milton’s religious and literary development serves as a welcome reminder of a common flaw in Milton scholarship, the tendency to paint a reductionist portrait of the mature Milton and then to fit the younger Milton into that same narrow interpretive frame.

Juster makes some unusual connections between Milton and theater – and concludes that, after all, the author of Paradise Lost might have been a fun kind of guy:

My only criticism of this admirable biography is that I would have liked to have seen the author push a little harder against certain scholarly misconceptions. … Not long ago we learned that Milton’s father — with whom he was close — had been part-owner of the Blackfriars Playhouse. Last year, Jason Scott-Warren identified extensive annotations (including proposed improvements) in a Shakespeare First Folio as those of Milton. It is time for scholars to look harder at the plays performed at his father’s theater (some of which were edgy for the time) and to determine if any of the language or ideas from plays performed there echoed through Milton’s work.

I would also have liked to have seen more pressure-testing of the standard portrayal of the young Milton as almost as dour as the later Milton. “Miltonic humor” might seem as unpromising as a Bill Clinton lecture on the virtues of chastity, but Milton seems to have been popular in his Cambridge years, and he even acted as the master of ceremonies for a student satirical event known as a “salting.” His epistolary elegies to his best friend, Charles Diodati, demonstrate his capacity for amiable teasing, but there is also a subversive wit in his other Latin poetry. Did this sense of humor evaporate, or are there satirical traces we have not noticed in the later works because we braced ourselves for grimness?

McDowell ends this book shortly before Milton’s doomed marriage to his first wife, but in the last paragraph adds that “the second half of Milton’s life is the story of how this gleaming vision of the poet’s powers became darkened, but not overshadowed, by the experience of revolution.” I take that assertion as a promise of a second volume — which is great news for lovers of this great poet.

Read the whole thing here.