“Jewish and Russian – not the same! Say you’re Jewish next time! It’s better! And good luck to you in Ukraine!” Poet/translator Nina Kossman’s convo with a stranger at 35,000 feet.

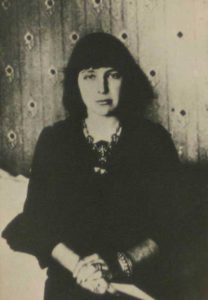

Monday, March 27th, 2023Russian poet Nina Kossman and a stranger sat next to each other on a recent flight from New York to Prague, en route to Ukraine. We’ve written about the U.S.-based writer’s translations of Marina Tsvetaeva here, but that was in a far less fraught time. A few minutes’ conversation between the two women laid bare the ongoing challenges of overlapping ethnicities, the terrible war, and the lifelong plight of the émigré. It went like this:

The woman in the seat next to me said something I didn’t understand right away. Something about a belt. I was thinking about something else, so I was a bit slow to react. Ah, a seatbelt! Is this my seatbelt or yours? I pointed at my seatbelt, already clasped on me, and then at hers, hanging from under her armrest.

“Ah!” she said, “Okay!” Her accent – the reason I didn’t understand her right away – sounded very familiar to me. “Do you speak Polish?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “And you? Where you from?” she said.

“I’m from the country that I’m sure you don’t like,” I said.

“Russia?” she guessed.

“Yes,” I said. “I was born in Russia. But I live here.”

“Why I don’t like?” she exclaimed with that mix of deep feeling and the hyper-drama I’m used to seeing in Eastern Europeans and which I notice in myself, too, once in a while.

“Russian people want war. So war.”

It sounded like a statement rather than a question, therefore I said, “The government wants the war, not the people. The people who approve of this war are just brainwashed.”

A very loud, emotional tirade ensued, and I suggested we not discuss politics. “I don’t want to fight with you while we are flying over the ocean.”

“You Russian,” she said. Again, it sounded like an assertion rather than a question, therefore I said, “Not really, although it’s true that I was born there.”

“What’s your last name?”

Ah, I thought, now I really feel like I am going to Eastern Europe. I knew what would follow my telling her my last name. Only in Russia and Eastern Europe I expect this question about my last name to be followed by “Not Russian,” and an instant later, by contemptuous “Jew?” Years ago, when I was a member of the now defunct PEN chapter “PEN/ Writers in Exile,” its Hungarian-born president never missed an opportunity to mispronounce my last name as “Koshman,” with barely concealed contempt, often followed by “Why is someone with the last name Koshman claiming to be Russian?”

That was in New York, where you don’t expect this sort of thing to happen, and it might be worth adding that the lady in question was not your usual illiterate antisemite but someone who knew every European writer personally and signed every PEN letter protesting the imprisonment of writers no matter where in the world the imprisonment took place, and herself was no lightweight as an author of critical studies of Hungarian literature as well as a literary translator. To prevent our conversation from taking the familiar route, I said calmly, “I’m Jewish, not Russian. Not ethnically Russian, that is.”

“Ah,” she said. “Then you not guilty. Not guilty of Russia war.”

“Right, I’m not responsible for this war – and not only because I’m Jewish and not Russian. “

“So why you say you Russian? Say ‘I Jewish,’ then no one thinks you guilty of this war.”

“In America, I’m seen as a Russian,” I say. “Being Jewish is a nationality only in Russia and Eastern Europe. In the rest of the world, and certainly in the U.S., you’re seen as Jewish if you go to a synagogue at least a couple times a year, that is, if you identify as a Jew, at least a Jew culturally, because here” – we were leaving the U.S., so I felt that “here” needed a clarification – ”in the U.S.,” I added, “Judaism is a religion, not a nationality as it is in Russia or Eastern Europe.”

“NO!” she said, with more feeling than I thought was necessary. “No! Say you Jewish, not Russian, then no one thinks you guilty. You not guilty of this war!”

“Whatever,” I said. “Perhaps we shouldn’t have this conversation here, just so we can have a peaceful flight.”

“You do not understand me! I say ‘Jewish – good!’ Not bad!”

“Okay,” I said, “Okay, okay.”

But we were not finished, because when a short pause during which she sat with her eyes closed was over, she said: “Tell me! Why you fly to Praga [Prague] now?”

“I’m flying to Prague just because I can’t fly straight to Ukraine. No passenger planes are flying to Ukraine, as you know.”

“I know!”

“Good,” I said, hoping this would be enough to end our conversation on a peaceful note.

I was wrong again. She sat in silence for a minute, and then said: “But why you go to Ukraine?”

“I want to work with animals that have been traumatized by the war.”

“But if you live in America, you can’t work in Ukraine! You need special papers to work there! Work papers! It’s another country! To work in another country, you need work papers!”

“I am not going to work for money. I’m going as a volunteer. Volontyor,” I used the Russian form of the word, thinking it might sound like Polish. “I wouldn’t work for money in a country at war.”

“Ah, you go there to help! Not to work!”

“Right.”

“That’s good!” she said Good luck!”

“Thank you,” I replied.

“My mother was a teacher of Russian in Poland. She went to Moscow many times. She said beautiful city! I wanted to see it but now I will never see it. Because of this war. Moscow is beautiful, right?”

“In a way.”

“But Leningrad is more beautiful. I always wanted to see it. Only if Putin dies! But he is only 70! And he has good Jewish doctors to keep him alive! War will end when he dies.”

“I hope it won’t be that long. But you never know.”

“Never know! That’s right! He wants to make the Soviet Union like in the old days. You know Poland was like number sixteen republic? It had fifteen republics – and Poland was sixteen!”

“Yes, I know.”

“It was like a train – one car, another car, Ukraina, Latvia, Belorussia, Estonia, Lithuania, fifteen republics, fifteen cars – and Poland car number sixteen! And after Ukraina, he will want to take Poland – to get his train back!”

“But Poland is part of NATO, so he won’t dare.”

“NATO is his fear! He sees NATO even where it is not!”

“Yes,” I said, “it’s a crazy fear of his.”

She touched my armrest gently.

“Jewish and Russian – not the same! Say you’re Jewish next time! It’s better! And good luck to you in Ukraine!”

“Thank you,” I said again. Like a real American, I’ve learned to say “thank you” to avoid saying anything substantial.

“I sleep now.”

“Okay,” I said, careful not to add “thank you” one more time.

She leaned back in her seat and closed her eyes. I tried to sleep, too, but nothing came of it, so I took out a piece of paper and a pencil and jotted down our conversation, while every word we had said was still fresh in my memory.

“The title has another meaning too. Having lived in two so- called ‘superpowers,’ i.e. having spent my childhood in the Soviet Union, where personal freedoms were curtailed, and my youth and adulthood in ‘something of its opposite’ (my way of referring to the US as a teenager) with its seemingly unlimited personal freedoms, I found both wanting. Being a ‘black sheep’ in the Soviet Union was not only painful psychologically. It pushed you to the edge of a very real abyss, since a threat of physical extermination was real. In the US, being a black sheep in a herd, a society where outsiders are accepted, yields only psychological pain. And so an immigrant from the former Soviet Union swings between these two. These are two very different kinds of ‘black-sheep-ness,’ one hard core and the other soft. The black sheep consciousness continues in the so-called free world, attenuated, without the attendant fear of physical extermination.”

“The title has another meaning too. Having lived in two so- called ‘superpowers,’ i.e. having spent my childhood in the Soviet Union, where personal freedoms were curtailed, and my youth and adulthood in ‘something of its opposite’ (my way of referring to the US as a teenager) with its seemingly unlimited personal freedoms, I found both wanting. Being a ‘black sheep’ in the Soviet Union was not only painful psychologically. It pushed you to the edge of a very real abyss, since a threat of physical extermination was real. In the US, being a black sheep in a herd, a society where outsiders are accepted, yields only psychological pain. And so an immigrant from the former Soviet Union swings between these two. These are two very different kinds of ‘black-sheep-ness,’ one hard core and the other soft. The black sheep consciousness continues in the so-called free world, attenuated, without the attendant fear of physical extermination.”