Indefatigable spirit: Remembering the legendary Robert Conquest (1917–2015)

Wednesday, August 5th, 2015

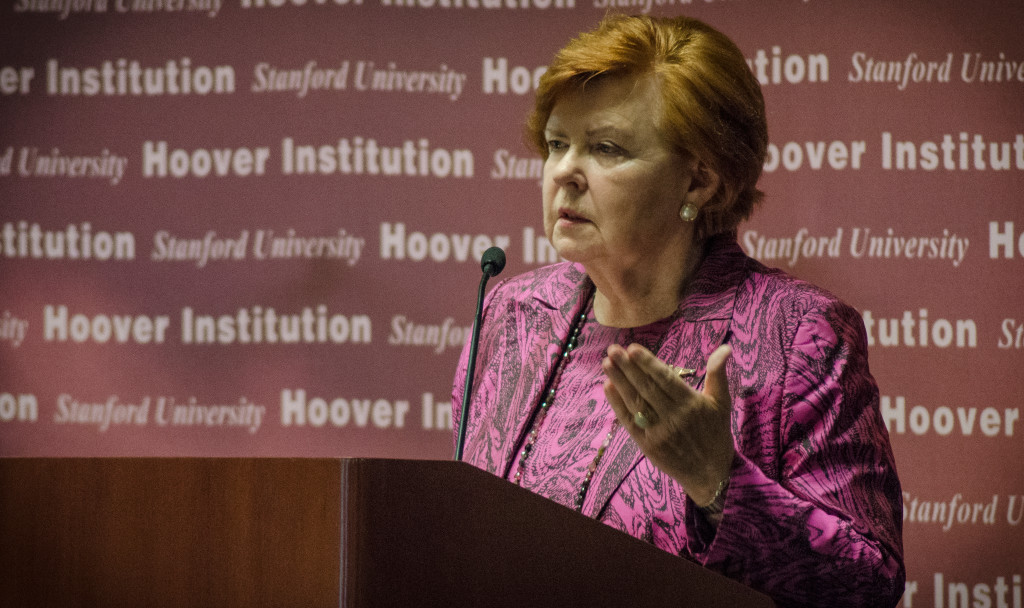

My favorite photo of him, by the matchless Linda Cicero.

To each of those who’ve processed me

Into their scrap of fame or pelf:

You think in marks for decency

I’d lose to you? Don’t kid yourself.

Robert Conquest wrote these lines in his last collection of poems, Penultimata (Waywiser, 2009). I suppose, although he was too polite to say so, I might be included in his roster, since we met when I interviewed him – here. Although the interview form is a kind of exploitation, I suppose, it didn’t exactly bring me either fame or pelf, but something much better. I expect my own “processing” will continue for some time now, as I digest, in future years, his work over a long lifetime. As everyone now knows, the Anglo-American historian and poet died on Monday, after long illness. He was 98. (Obituaries from the New York Times here, the Wall Street Journal here, and London’s Telegraph here.) He was working until his last few weeks on an unfinished memoir called Two Muses. I hope there’s enough of it to publish.

The short quatrain above refers, I expect, to his dirty limericks and light verse, rather than his sobering prose and more serious poems. “Limericks are not very gentlemanly – or it’s a special kind of gentleman,” he told me. But perhaps the lightness of much of his verse was a necessary psychological counterbalance to the grim history he relentlessly documented in the books that were his major achievement, chronicling the devastation caused by the Soviet regime, throughout its existence. His landmark book, The Great Terror reads like a thriller, and is a detailed log of Stalin’s assassinations, arrests, tortures, frame-ups, forced confessions, show trials, executions and incarcerations that destroyed millions of lives. The book instantly became a classic of modern history, and other titles followed, including The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (1986) and a 1977 translation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn‘s 1,400-line poem, Prussian Nights, undertaken at the author’s request.

The late Christopher Hitchens, a close friend, praised Bob’s “devastatingly dry and lethal manner,” hailing him as “the softest voice that ever brought down an ideological tyranny.” Timothy Garton Ash said, “He was Solzhenitsyn before Solzhenitsyn.”

When he revised The Great Terror for republication in 1990, his chum Kingsley Amis proposed a new title, I Told You So, You Fucking Fools.” Catchy title, although Bob settled for the more circumspect The Great Terror: A Reassessment.

Mentor and mentee, 2009.

“His historical intuition was astonishing,” Norman Naimark told the New York Times (we’ve written about Norm here and here and here). “He saw things clearly without having access to archives or internal information from the Soviet government. We had a whole industry of Soviet historians who were exposed to a lot of the same material but did not come up with the same conclusions. This was groundbreaking, pioneering work.”

My 2010 interview, however, wasn’t my first encounter with the poet-historian, although it was his first encounter with me. I was one of a throng of people who attended a 2009 ceremony at Hoover event when Radosław Sikorski, then Poland’s minister of foreign affairs, awarded him the country’s Order of Merit. (I wrote about the occasion here. Incidentally, Bob received a U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005.)

“His books made a huge impact on the debate about the Soviet Union, both in the West and in the East. In the West, people had always had access to the information about Communism but were not always ready to believe in it,” said Sikorski at that time. “We longed for confirmation that the West knew what was going on behind the Iron Curtain. Robert Conquest’s books gave us such a confirmation. They also transmitted a message of solidarity with the oppressed and gave us hope that the truth would prevail.”

An excerpt from my 2010 article:

Susan Sontag was a visiting star at Stanford in the 1990s. But when she was introduced to Robert Conquest, the constellations tilted for a moment.

“You’re my hero!” she announced as she flung her arms around the elderly poet and acclaimed historian. It was a few years since she had called communism “fascism with a human face” – and Conquest, author of The Great Terror, a record of Stalin’s purges in the 1930s, had apparently been part of her political earthquake.

Sitting in his Stanford campus home last week and chatting over a cup of tea, the 93-year-old insisted it’s all true: “I promise. We had witnesses.” His wife, Liddie, sitting nearby confirmed the account, laughing.

Conquest, a Hoover Institution senior research fellow emeritus, moves gingerly with a walker, and speaks so softly it can be hard to understand him. But his writing continues to find new directions: He published his seventh collection of poems last year and a book of limericks this year, finished a 200-line poetic summa and is working on his memoirs.

He’s been a powerful inspiration for others besides Sontag. In his new memoir, Hitch-22, Christopher Hitchens described Conquest, who came to Stanford in 1979, as a “great poet and even greater historian.” The writer Paul Johnson goes further, calling Conquest “our greatest living historian.”

He deserved the medal. In 2005.

I made a few return visits to that immaculate and airy Stanford townhouse on the campus. Liddie was always bubbly, intelligent, and hospitable – a thorough Texan, and always a charming and welcoming hostess. Often the two of us were talking so quickly and with such animation Bob couldn’t keep up – he spoke barely above a whisper. He was still a terrific conversationalist, one just had to listen harder. Among his considerable gifts, “He had a wicked sense of humor and he loved to laugh: the look of playful delight that animated his face as he nailed a punch line is impossible to forget,” said Bert Patenaude (I also wrote about Bert here). “His poems and limericks convey a sense of his mischievousness—and naughtiness—and his late poems chronicle the aging process with sensitivity and, one is easily persuaded, acute psychological insight.”

Another of our mutual friends, the poet R.S. Gwynn, agreed: “As a poet Bob is funny, intensely lyrical and deeply reflective,” he said. “Whenever I read him I think of how rarely we are allowed to see a mind at work, and what a mind it is.” (I’ve written about Sam Gwynn here and here.)

Bert said that Bob’s final speaking appearance on the Stanford campus may well have been his participation in an annual book event, “A Company of Authors,” where he discussed Penultimata on April 24, 2010. “Bob seemed frail that day, and at times it was difficult to hear him and to understand his meaning, but no one in the room could doubt that the genial elderly man up there reciting his poetry could have carried the entire company of authors on his back. Seated next to me in the audience was a Stanford history professor, a man (not incidentally) of the political left, someone I had known since my graduate student days—not a person I would ever have imagined would be drawn to Bob Conquest. Yet he had come to the event, he told me, specifically in order to see and hear the venerable poet-historian: ‘It’s rare that you get to be in the presence of a great man. Robert Conquest is a great man.’ Indeed he was.”

In the last few months, I tried to visit – but the Conquests were either traveling or packing, or else, more distressingly, he was in the hospital or recovering from a round of illnesses. And finally time ran out altogether. Time always wins. We don’t have time; it has us.

Postscript on 8/7: My publisher Philip Hoy pointed out in the comments section below that Penultimata was not Bob’s final collection of poems, it was (as the name suggests) a penultimate one. Blokelore & Blokesongs was published by Waywiser in 2012.

A pleasure to know you, sir. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)