Today at the Swedish PEN-club (Photo: Joanna Helander)

This weekend Olga Tokarczuk gave her Nobel lecture, a much-anticipated event in literary world. Her topic: “The Tender Narrator.” It was a knock-out.

Her explanation of the title:

Tenderness is spontaneous and disinterested; it goes far beyond empathetic fellow feeling. Instead it is the conscious, though perhaps slightly melancholy, common sharing of fate. Tenderness is deep emotional concern about another being, its fragility, its unique nature, and its lack of immunity to suffering and the effects of time. Tenderness perceives the bonds that connect us, the similarities and sameness between us. It is a way of looking that shows the world as being alive, living, interconnected, cooperating with, and codependent on itself.

Literature is built on tenderness toward any being other than ourselves. It is the basic psychological mechanism of the novel. Thanks to this miraculous tool, the most sophisticated means of human communication, our experience can travel through time, reaching those who have not yet been born, but who will one day turn to what we have written, the stories we told about ourselves and our world.

A few excerpts:

The category of fake news raises new questions about what fiction is. Readers who have been repeatedly deceived, misinformed or misled have begun to slowly acquire a specific neurotic idiosyncrasy. The reaction to such exhaustion with fiction could be the enormous success of non-fiction, which in this great informational chaos screams over our heads: “I will tell you the truth, nothing but the truth,” and “My story is based on facts!”

Fiction has lost the readers’ trust since lying has become a dangerous weapon of mass destruction, even if it is still a primitive tool. I am often asked this incredulous question: “Is this thing you wrote really true?” And every time I feel this question bodes the end of literature.

***

Reading in Yonkers last year, in the home of Izabela Barry.

I have never been particularly excited about any straight distinction between fiction and non-fiction, unless we understand such a distinction to be declarative and discretionary. In a sea of many definitions of fiction, the one I like the best is also the oldest, and it comes from Aristotle. Fiction is always a kind of truth.

I am also convinced by the distinction between true story and plot made by the writer and essayist E.M. Forster. He said that when we say, “The king died and then the queen died,” it’s a story. But when we say, “The king died, and then the queen died of grief,” that is a plot. Every fictionalization involves a transition from the question “What happened next?” to an attempt at understanding it based on our human experience: “Why did it happen that way?”

Literature begins with that “why,” even if we were to answer that question over and over with an ordinary “I don’t know.”

***

Humanity has come a long way in its ways of communicating and sharing personal experience, from orality, relying on the living word and human memory, through the Gutenberg Revolution, when stories began to be widely mediated by writing and in this way fixed and codified as well as possible to reproduce without alteration. The major attainment of this change was that we came to identify thinking with language, with writing. Today we are facing a revolution on a similar scale, when experience can be transmitted directly, without recourse to the printed word.

There is no longer any need to keep a travel diary when you can simply take pictures and send those pictures via social networking sites straight into the world, at once and to all. There is no need to write letters, since it is easier to call. Why write fat novels, when you can just get into a television series instead? Instead of going out on the town with friends, it would be better to play a game. Reach for an autobiography? There’s no point, since I am following the lives of celebrities on Instagram and know everything about them.

It is not even the image that is the greatest opponent of text today, as we thought back in the twentieth century, worrying about the influence of television and film. It is instead a completely different dimension of the world—acting directly on our senses.

***

With translator Jennifer Croft, after winning the Man Booker Prize in 2018 (Photo: Janie Airey/Man Booker Prize)

The flood of stupidity, cruelty, hate speech and images of violence are desperately counterbalanced by all sorts of “good news,” but it hasn’t the capacity to rein in the painful impression, which I find hard to verbalize, that there is something wrong with the world. Nowadays this feeling, once the sole preserve of neurotic poets, is like an epidemic of lack of definition, a form of anxiety oozing from all directions.

Literature is one of the few spheres that try to keep us close to the hard facts of the world, because by its very nature it is always psychological, because it focuses on the internal reasoning and motives of the characters, reveals their otherwise inaccessible experience to another person, or simply provokes the reader into a psychological interpretation of their conduct. Only literature is capable of letting us go deep into the life of another being, understand their reasons, share their emotions and experience their fate.

A story always turns circles around meaning.

***

In Doctor Faustus Thomas Mann wrote about a composer who devised a new form of absolute music capable of changing human thinking. But Mann did not describe what this music would depend on, he merely created the imaginary idea of how it might sound. Perhaps that is what the role of an artist relies on―giving a foretaste of something that could exist, and thus causing it to become imaginable. And being imagined is the first stage of existence.

Read the whole thing here.

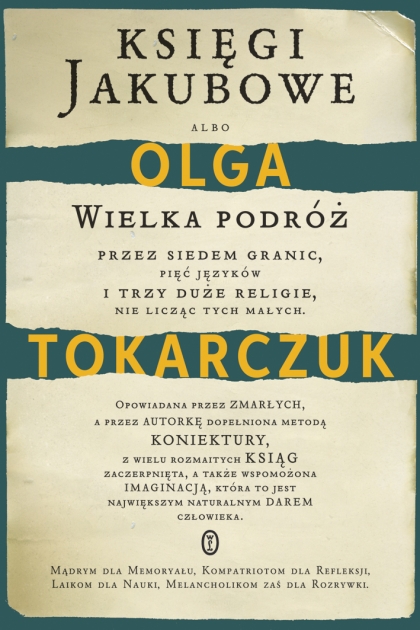

You’re also translating Tokarczuk’s magnum opus, the 900-page epic The Books of Jacob, which won the “Polish Booker” [That would be the Nike – ED.], and which is slated to be released in 2019. What can readers expect?

You’re also translating Tokarczuk’s magnum opus, the 900-page epic The Books of Jacob, which won the “Polish Booker” [That would be the Nike – ED.], and which is slated to be released in 2019. What can readers expect?