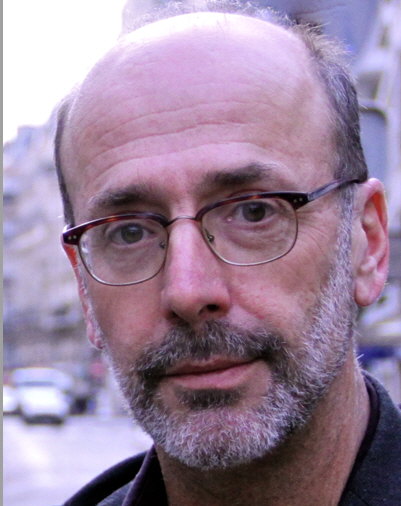

Au revoir, novelist Neil Gordon (1958-2017), who wrote about the purity of conviction, the reality of engagement

Friday, May 26th, 2017The writer Neil Gordon has died, after a long battle with cancer on May 19 in New York City.

My acquaintance with him was slight, but memorable. We had a conversation over coffee in Paris, when I was a visiting writer at the American University of Paris, during Neil’s term as dean there.

But I knew another side of him. By one of those odd coincidences that are considered far-fetched when we read them in Dickens, Neil turned out to be the brother-in-law of a longstanding friend, the writer Eren Göknar. Neil was married to Eren’s sister, Esin Göknar, photo editor of the New York Times Magazine, who had cared for him during his final illness. His brother-in-law, Erdağ Göknar, a translator of Orhan Pamuk, was a recent fellow at the Stanford Humanities Center.

Neil was born in South Africa in 1958. His family emigrated two years later to escape the apartheid government. “His mother, Sheila Gordon, was also a writer, and his father Harley Gordon was a dedicated physician who cared for the underserved all his life,” Eren told me. “Sheila wrote a delightful book about Neil called Monster in the Mailbox, about his waiting and waiting for the monster he bought through a newspaper ad. Remember the ads for X-ray vision glasses in the back of comic books in the ’60s?”

He was primarily a historical and political novelist. He published four novels, one set in the history of the Holocaust and the state of Israel; (Sacrifice of Isaac) the second about Israel, America, and the arms trade (The Gunrunner’s Daughter); the third about the radical Left in America during the War in Vietnam (The Company You Keep), which was made into a 2012 film with Robert Redford and Shia LaBoeuf. The fourth about the story of the American Left, from the Spanish Civikl War to Occupy Wall Street (You’re a Big Girl Now).

He was primarily a historical and political novelist. He published four novels, one set in the history of the Holocaust and the state of Israel; (Sacrifice of Isaac) the second about Israel, America, and the arms trade (The Gunrunner’s Daughter); the third about the radical Left in America during the War in Vietnam (The Company You Keep), which was made into a 2012 film with Robert Redford and Shia LaBoeuf. The fourth about the story of the American Left, from the Spanish Civikl War to Occupy Wall Street (You’re a Big Girl Now).

He worked for many years at The New York Review of Books and was the founding Literary Editor of The Boston Review. He spent three years in Paris serving as dean, vice President, and professor of comparative literature at the American University of Paris, where I met him. He returned to the U.S. and taught at the New School.

He wrote: “My courses, whether writing or literature classes, like my novels, focus on the intersection between individuals and the political history that surrounds them; on the representation of lived political and historical experience in fiction; on the mechanics of the sympathetic imagination; as well as on the forms of the literary, political, and cultural essay.”

He has a PhD in French literature from Yale, but he had his academic roots in Michigan, where he took his bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan and bagged two Hopwood Writing Awards along the way (like Humble Moi), and also met his future wife, Asin.

In 1994, he became the first literary editor of the Boston Review. A couple links to his work there: an essay on John Fante and a moving autobiographical reflection, “The Last Time I Saw Yaakov.”

From Joshua Cohen‘s eloquent tribute, over at the Boston Review:

Neil wrote four very fine novels (Sacrifice of Isaac remains my favorite), all thrillers mixing strong narratives, deeply-researched history, and serious political ambition. Whatever the topic, I always heard Neil wrestling with the same problem: about purity of conviction and worldy engagement. Sometimes he wrote admiringly of the purity, sometimes he worried about its degeneration into fanaticism, and always he was uneasy about the distance it created from the individual lives that ultimately matter (as it had distanced his young German friend Yaakov). So you will not be surprised to hear that Neil’s voice always sounded a little anxious.

Until our final phone conversation in February of this year. Neil was dying of cancer: his medical options had run out and while he was trying to keep his hopes up, he knew that he did not have much more time. What I heard this time was not anxiety but calm gratitude, all focused on the people—largely the people in his family—who had helped to enable him to have such a good life. He was free from worries about purity and survival and filled instead with an affirming sense of acceptance and an unambivalent love. Neil told me that he was, finally and deeply, happy.

He will be missed by many, but most of all his wife Esin, his daughter and son Leila and Jake Gordon, both born in New York City, a sister Philippa, a brother David, and nieces Sophie, Eve, Anne, Leyna and Dillon Lightman.