Winston Churchill and “the English-speaking club”

Sunday, January 3rd, 2016 Winston Churchill the speaker was a force of nature. His rhetorical powers had a critical role to play in saving Europe from the biggest threat it had faced in a millennia, perhaps ever. There’s a reason why his rhetoric worked. Paul Reid writes in The Last Lion: Defender of the Realm 1940-1965: “Churchill, like Samuel Johnson and Shakespeare, could string together phrases that resonated with Glasgow pub patrons, Welsh coal miners, and Cockney laundresses, as well as with the Harold Nicolsons and Lady Astors. At his dinner table or in the Commons during Questions, he sprayed the room with fusillades of bons mots. But his broadcasts and speeches were strategic assaults, not tactical, and were crafted with infinite care. His broadcasts sound so English, but in fact their structural foundations date to Cicero.”

Winston Churchill the speaker was a force of nature. His rhetorical powers had a critical role to play in saving Europe from the biggest threat it had faced in a millennia, perhaps ever. There’s a reason why his rhetoric worked. Paul Reid writes in The Last Lion: Defender of the Realm 1940-1965: “Churchill, like Samuel Johnson and Shakespeare, could string together phrases that resonated with Glasgow pub patrons, Welsh coal miners, and Cockney laundresses, as well as with the Harold Nicolsons and Lady Astors. At his dinner table or in the Commons during Questions, he sprayed the room with fusillades of bons mots. But his broadcasts and speeches were strategic assaults, not tactical, and were crafted with infinite care. His broadcasts sound so English, but in fact their structural foundations date to Cicero.”

But Churchill was above all a writer, and a professional one (we wrote about that here). According to Reid:

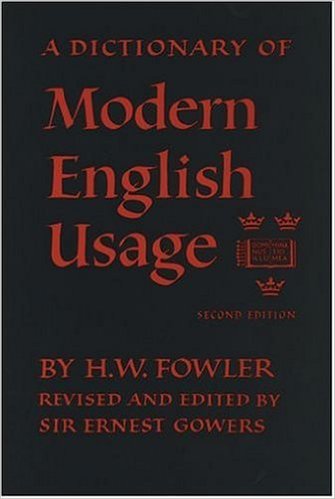

“Churchill had been a professional writer before he became a statesman; he had supported his family with a tremendous stream of books and articles. His love of the language was deep and abiding, he had mastered it as few men have, and he was quick to correct anyone who abused it, especially those who tried to camouflage sloppy thinking with the flapdoodle of verbose military jargon or bureaucratese. He believed, with F.G. Fowler, that big words should not be used when small words will do, and that English words were always preferable to foreign words. He said: ‘Not compressing thought into a reasonable space is sheer laziness.’ On his orders ‘Communal Feeding Centres’ were renamed ‘British Restaurants,’ as ‘Local Defense Volunteers’ had become ‘Home Guard.’ And why not ‘ready-made’ rather than ‘prefabricated’? ‘Appreciate that’ was a red flag for him; he always crossed it out and substituted ‘recognize that.’ Another was ‘intensive’ when ‘intense’ was required. Once [Churchill’s private secretary] John Martin, driving along the Embankment with him, described the winding of the Thames as ‘extraordinary.’ Churchill corrected him: ‘Not “extraordinary” All rivers wind. Rather, “remarkable.”‘ In the margins of official documents, he often quoted Fowler’s Modern English Usage, a copy of which he sent to Buckingham Palace on his first Christmas as prime minister.

“John Martin believed that the P.M.’s ‘interest in basic English was inspired by politics rather than linguistics: it was a means of promoting “the English-speaking club.”‘ Certainly that was one reason. He believed that all countries where English was spoken, including America, should merge. Here lay a profound contrast with the foreign policies of his predecessors at Downing Street. They had focused upon the Continent and the various combinations of the great powers there. Neville Chamberlain had referred to the United States with amusement and contempt, and called Americans ‘creatures.’ But Churchill, though a European patriot, looked westward, and not only because he knew Hitler could not be crushed without American troops. British to the bone, he was nevertheless the son of an American mother, and long before the war, he had envisaged a union of the world’s English-speaking peoples: the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and the far-flung colonies of the British Empire.”

“John Martin believed that the P.M.’s ‘interest in basic English was inspired by politics rather than linguistics: it was a means of promoting “the English-speaking club.”‘ Certainly that was one reason. He believed that all countries where English was spoken, including America, should merge. Here lay a profound contrast with the foreign policies of his predecessors at Downing Street. They had focused upon the Continent and the various combinations of the great powers there. Neville Chamberlain had referred to the United States with amusement and contempt, and called Americans ‘creatures.’ But Churchill, though a European patriot, looked westward, and not only because he knew Hitler could not be crushed without American troops. British to the bone, he was nevertheless the son of an American mother, and long before the war, he had envisaged a union of the world’s English-speaking peoples: the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and the far-flung colonies of the British Empire.”

That’s strategy, not tactics.

P.S. Speaking of Cicero, my colleague Frank Wilson over at Books Inq reminds me that today is the birthday of the Roman philosopher, politician, lawyer, orator, political theorist, consul and constitutionalist, with this quotation, which is altogether fitting for a discussion of Churchill: “To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child.” — Marcus Tullius Cicero, born on this date in 106 B. C.