“Ecstatic Pessimist”: Peter Dale Scott’s new book on poet, friend Czesław Miłosz is out!

Wednesday, August 2nd, 2023

Author Peter Dale Scott‘s newest book has been a long time in the making. Peter has been sharing his drafts of Ecstatic Pessimist: Czeslaw Milosz, Poet of Catastrophe and Hope with me for at least a decade, and the road to publication has been long and arduous. The volume was finally published by Rowman & Littlefield in July. So a celebration is in order.

“Book Passage,” a vast and legendary bookstore in Corte Madera, fêted the occasion with a reading and onstage conversation on the hot afternoon of Sunday, July 16.

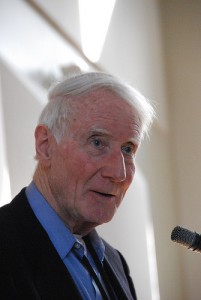

I made the long trip from Palo Alto to Marin to hear the nonagenarian poet, translator, author, Berkeley professor, and former Canadian diplomat – spending time with Peter is always a good idea. His wisdom is formidable and his anecdotes insightful. Many of the people gathered that afternoon thought so, too: it was a gratifyingly full house, and a very friendly one, as well. (Photos by the Book Passage’s Jonathan Spencer.)

Peter was the first translator of Milosz into English, collaborating with the poet in the early 1960s. He is also the first translator for Zbigniew Herbert. For that, the Anglophone world owes him a double debt of gratitude. And so does the Polish world. The work of Milosz’s translators then and since have brought Polish literature to the fore as one of the world’s great literary treasures. (Early in his exile, Milosz referred to Polish despairingly as an “unheard-of tongue.” How times have changed!)

My two cents are included on a back cover blurb: “We are fortunate to have Scott as a guide to one of the greatest poets of our times, offering us a wise, insightful, and deeply learned journey through Milosz’s poems and life in these pages.” And so he does.

Peter discussed his book and read several poems and passages before he shared the onstage conversation with Norman Fischer, a poet and Buddhist priest, and psychologist Sylvia Boorstein.

The excerpt he read from his book touched on his long, sometimes conflicted, but unforgettable relationship with the poet:

“I can only say that I have tried to be true to the Milosz I knew and loved in the early 1960s, the man who cared enough about literature to devote his life to it, and yet rejected the offer of a farm where he would not have had to do anything else,” he said. [Friend Thornton Wilder offered him that pastoral possibility when the Polish poet defected.]

Here’s what he read:

“‘What is poetry, that does not change/Nations or people?’ That question, not yet translated into English, electrified me in Milosz’s home in 1961, when I first read it. It was my hope, then, that Milosz’s poetry might help change not just American ‘poetry of the “well-wrought urn”’ but America itself, indeed the world.”

“I believed, in short, in the efficacy and potential of Milosz’s strategy for cultural evolution (ethogeny) or what Milosz called his ‘unpolitical politics.’ When I began this book … I was thinking of the power of poetry to enhance and advance politics, as I noted in the influence of Paradise Lost, described by historians, on the American Revolution.

“Thus the doorway to my thinking … on the acknowledged contribution of Milosz’s writings, both in poetry and prose, to the success of the Polish Solidarity Movement.

“That is still my hope today. But writing this book has changed me, just as Milosz himself evolved. I now consider his role in Solidarity to be incidental, almost a footnote, to his global role in renewing shared values twoard ‘an open space ahead,’ a revitalized mindset beyond conservatism, modernism, and postmodernism.”

Copies of the book were snapped up and purchased afterward and Peter signed them – a gratifying reception for the 94-year-old poet who still has more projects to finish. Thanks and congratulations to Peter, long may he live and write!

“Magpiety.” I had thought the title came from Nobel poet

“Magpiety.” I had thought the title came from Nobel poet