Who’s got the ring now? “Tolkien has become a monster,” says his son.

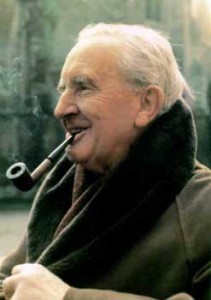

Friday, January 4th, 2013 A few days ago we wrote about the Tolkien, Auden, and an Evening of Musrooms and Elvish, describing the nerdy cult that has evolved around J.R.R. Tolkien‘s Hobbit and Lord of the Rings.

A few days ago we wrote about the Tolkien, Auden, and an Evening of Musrooms and Elvish, describing the nerdy cult that has evolved around J.R.R. Tolkien‘s Hobbit and Lord of the Rings.

But Le Monde has described another side of the Tolkien fever, as seen by the author’s heirs: “Tolkien has become a monster, devoured by his own popularity and absorbed into the absurdity of our time,” [son] Christopher Tolkien observes sadly. “The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me. The commercialization has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing. There is only one solution for me: to turn my head away.”

Son Christopher, who has edited Silmarillion as well as a 12-volume History of Middle-Earth, has dedicated his life to extending and completing his father’s work (but not the way director Peter Jackson has envisioned). When I say “his life” – I don’t mean just the adult end of it. The involvement began almost from the cradle:

Christopher Tolkien’s oldest memories were attached to the story of the beginnings, which his father would share with the children. “As strange as it may seem, I grew up in the world he created,” he explains. “For me, the cities of The Silmarillion are more real than Babylon.”

On a shelf in the living room, not far from the handsome wooden armchair in which Tolkien wrote Lord of the Rings, there is a small footstool covered in worn needlepoint. This is where Christopher sat, age 6 or 7, to listen to his father’s stories. “My father could not afford to pay a secretary,” he says. “I was the one who typed and drew the maps after he did the sketches.”

Little by little, starting in the late 1930s, The Lord of the Rings took shape. Enlisted in the Royal Air Force, Christopher left for a South African air base in 1943, where every week he received a long letter from his father, as well as the episodes of the novel that was under way.

Tolkien’s death in 1973 brought to Christopher’s doorstep “70 boxes of archives, each stuffed with thousands of unpublished pages. Narratives, tales, lectures, poems of 4,000 lines more or less complete, letters and more letters, all in a frightening disorder. Almost nothing was dated or numbered, just stuffed higgledy-piggledy into the boxes,” according to the article. Christopher, a professor at New College in Oxford at the time, junked his day job and took on decades of labor on his father unfinished works. “During all that time, I watched him type with three fingers on an old machine that had belonged to his father,” according to Christopher’s wife Baillie. “You could hear it all the way down the street!”

The nerdishness I described a few days ago illustrates the degree of Christopher’s success in conveying the world of Middle-Earth. Tolkien’s vision, “like that of the Grimms’ fairy tales of the previous century, has become part of the mental furniture of the western world,” writes Thomas Alan Shippey. But the family objects to the way the film has reduced Tolkien’s world to an action movie for teenagers, and a product line that includes comics, videogames, rock music, toys, bumper stickers, stationery, and God knows what else.

With the release of the new film, the Tolkiens are bracing themselves for yet more. “We will have to put up the barricades,” says Baillie Tolkien, smiling.

Read the Le Monde article in English translation at Worldcrunch here.