Book Haven friend Philip Fried of the Manhattan Review has just published a new collection, Interrogating Water and Other Poems, published by Salmon Poetry in Ireland. What could be more fitting, given the publisher, than a poem about water? The title poem has been generating some buzz – it was featured in Verse Daily already here. Philip’s poetry is intense – not something to hit before you’ve had your morning coffee – and is often based in political events of the day. So is this one. You’ll get a hint of it in the comments he wrote to me about it:

I like to engage with the intractable language that surrounds us: ad-talk, military jargon, scientific lingo—all of which can be found on the Internet. As in plate tectonics, the resulting collisions—if you are skillful enough—will result in a tremor, and the tremor itself is the poetry. Or, to shift the metaphor in this case, the poetry is in the current that leaps the gap between two apparently opposite poles.

I like to engage with the intractable language that surrounds us: ad-talk, military jargon, scientific lingo—all of which can be found on the Internet. As in plate tectonics, the resulting collisions—if you are skillful enough—will result in a tremor, and the tremor itself is the poetry. Or, to shift the metaphor in this case, the poetry is in the current that leaps the gap between two apparently opposite poles.

The two poles of language in this poem, of course, are the dry but suggestive text of a home electrolysis experiment and a contrasting, “sublime,” and politically colored description of water as a “non-state actor.” The reader, one hopes, will be prompted to jump the gap, providing the electricity.

The poem is—and I hope this is evident—a meditation on torture, with allusions to the “interrogation” of nature conducted by science and the theme of control. (A kind of water-boarding of water; or, as one reader put it, Art meets Science meets CIA.) As to its origin, I seem to remember being intrigued by the language of the electrolysis experiment, which seemed to call out for a contrasting sublimity. An appealing formal solution was to “package” the sublimity in short lines and brief stanzas.

The Literary Review declared, “In realms between and including the Almighty and actuarial tables, Fried speaks every language faithfully and eloquently. Rejoice! Read!” The poet A.R. Ammons has said of Philip’s poems: “Here in a major new testament the great questions are considered, represented – how the large and small inhabit each other, how indifferences allow differences, how the palpable can be the residence of the widest spirit. The graphic and the philosophical, the human and the godly interplay in a quiet attentiveness, explosive with realization and recognition.”

See what you think:

Interrogating Water

Imagine you are interrogating water,

Imagine you are interrogating water,

coercing the hydrogen and oxygen

to violate their bonds, give up each other.

Water, a non-state actor,

flows secretly over borders,

precipitates, infiltrates,

gathers in pools, conspires

with bacteria and mosquitoes

You can perform this at home with simple materials.

All you need is a battery, two no. 2 pencils,

salt, thin cardboard, electrical wire, a glass …

Foe of stability,

it erodes in drizzles,

revolts in tsunamis, riots

in floods, and from covert puddles

takes part in uprisings

… of water. Sharpen the pencils at both ends.

Cut the cardboard to fit over the glass.

Insert the pencils in cardboard, an inch apart.

Claims transparency

but under every skin

is another, while fluid rib

over rib will hide the atomic

truth in a wavering cage

Using the wires, connect the tips of each pencil

to opposite poles of the battery, then place

the other ends of the pencils into the water.

Excitable even in teacups

its sloshing shifting mass

can menace levees and dams

heave at the ocean’s crust

subverting the Earth’s rotation

The molecules will confess in tiny bubbles

of hydrogen and chlorine gas, at the pencil

tips, chlorine masking the fugitive oxygen.

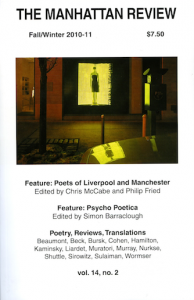

Over the weekend, my occasional correspondent Philip Fried, editor of the Manhattan Review (we’ve written about him here and here and here), dropped me a note. He’s rightly chuffed with the new review that’s just come out for his Interrogating Water (Salmon, 2014), which just appeared in The Poetry Review, journal of the British Poetry Society. In her review, poet Carol Rumens considered Phil’s book alongside Martha Kapos‘s The Likeness (Enitharmon).

Over the weekend, my occasional correspondent Philip Fried, editor of the Manhattan Review (we’ve written about him here and here and here), dropped me a note. He’s rightly chuffed with the new review that’s just come out for his Interrogating Water (Salmon, 2014), which just appeared in The Poetry Review, journal of the British Poetry Society. In her review, poet Carol Rumens considered Phil’s book alongside Martha Kapos‘s The Likeness (Enitharmon).