“He was so good at everything he did”: Robert Conquest and his poems of “elegant irreverence” in WSJ

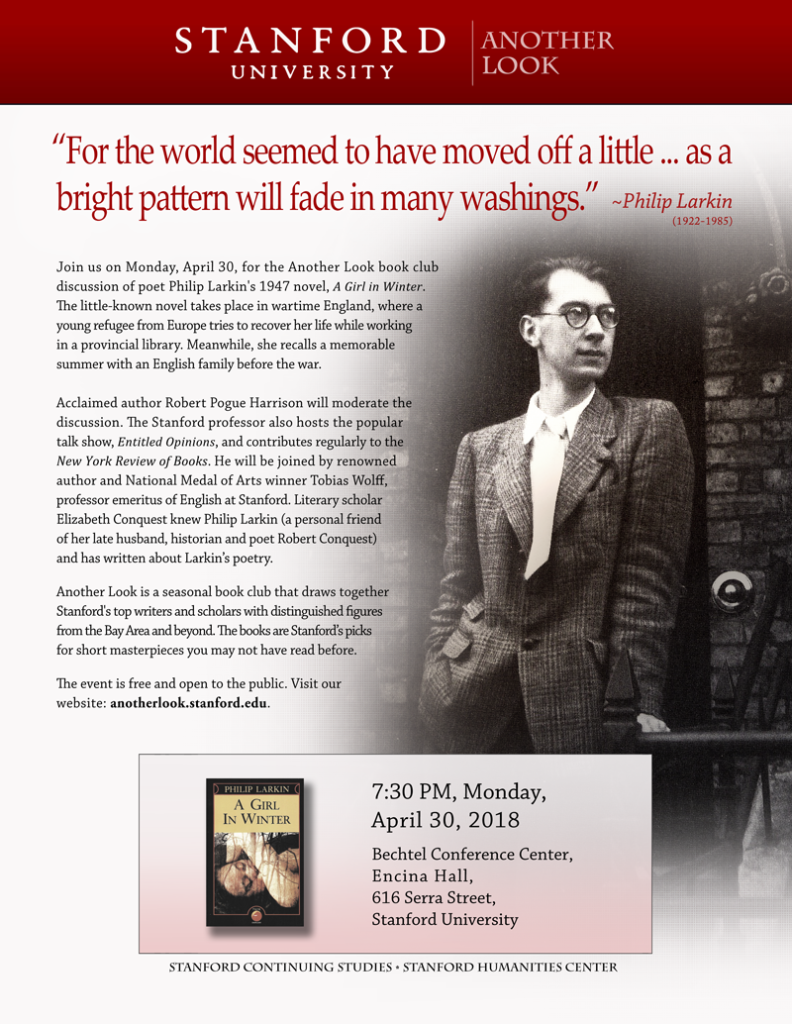

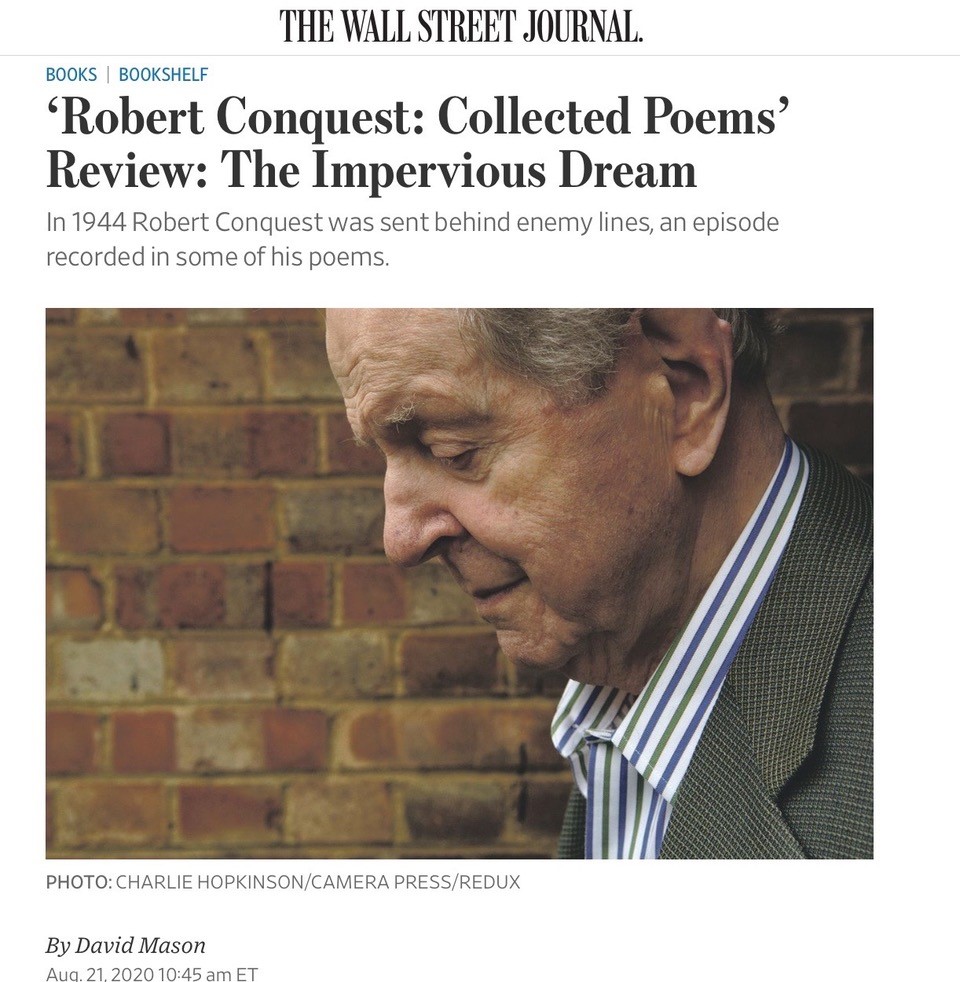

Sunday, August 23rd, 2020Robert Conquest‘s Collected Poems is out at last, thanks to the assiduous efforts of his widow, the literary scholar Elizabeth Conquest. And also to Philip Hoy of Waywiser, who is my publisher as well. But thanks especially, in the last few days, to David Mason, who has written a review, “The Impervious Dream,” in the Wall Street Journal. We’ve written about Stanford’s Bob Conquest, who died in 2015 at 97, here and here and here. among other places. We’ve written about Liddie Conquest here and here and here. Phil Hoy is here, and David Mason here and here and here.

An excerpt from the review:

He was so good at everything he did—soldier, diplomat, historian and poet—that I wouldn’t be surprised to learn he also left behind a few sonatas and paintings in oil. His histories of the Soviet Union’s failures and atrocities include The Great Terror (1968) and The Harvest of Sorrow (1986), meticulously researched and humane investigations of a criminal state, surely among the major historical achievements of the 20th century. His television documentary series, Red Empire (1990), distills this work and makes grimly compelling viewing.

But Conquest first came to readers’ attention as a poet of sophistication and grace, and as the editor of two New Lines anthologies (1956 and 1963) that introduced a group of English poets known as The Movement, among them Philip Larkin, Elizabeth Jennings, Kingsley Amis and Thom Gunn. Though his poetry was pushed aside by his work as a public intellectual, we now have the opportunity to see it whole for the varied, remarkable accomplishment it is, a poetry praising “the great impervious dream / On which the world’s foundations rest.”

In her editor’s note for this new “Collected Poems,” the poet’s widow, Elizabeth Conquest, gives us a glimpse of his character: “Kingsley Amis, complaining to Philip Larkin of getting old, wrote: ‘Bob just goes on and on, as if nothing has happened.’ And so he did, walking a mile at light infantry pace until his 89th year, dying at age 98 in the midst of editing his 34th book, while also writing a poem.” Readers tempted to dismiss Conquest as a dinosaur for his lyric formality, his Old World erudition and his occasionally patronizing love of women would be too hasty. This is a civil voice, a man who in his poem “Galatea” praises both “passion and reserve.” An early poem about the Velázquez painting known as “The Rokeby Venus” begins, “Life pours out images, the accidental / At once deleted when the purging mind / Detects their resonance as inessential: / Yet these may leave some fruitful trace behind.” Conquest positioned himself between the life lived and its ideal expression, yet never lost the realism that chastened ornament.

I am particularly moved by Conquest’s poems about World War II. Another early work, “For the Death of a Poet,” echoes elders such as Eliot and Auden, while touching a nerve of its own: “But how shall I answer? I am like you, / I have only a voice and the universal zeals / And severities continue to state loudly / That all is well. / Even the landscape has no help to offer./A man dies and the river flows softly on. / There is no sign of recognition from the calm/And marvellous sky.”

Read the whole thing here (warning: paywall).

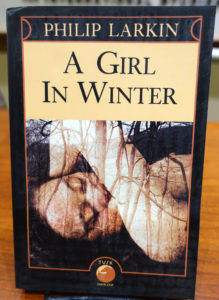

The sparks were lively and the balance of personalities was effective and harmonious. Toby’s background as a soldier was helpful in explaining Robin’s emotional state at the end of the book, and he also shared some chilling details of the destruction of Larkin’s hometown, Coventry. Liddie reflected on Larkin’s life and poetry – and she also shared a passage he wrote in a 1977 letter to her husband. The three discussed in detail the signficance of the noisy tick-tock of Katherine’s watch. But I won’t spoil it for you by quoting the end of the book, only part of the penultimate paragraph instead:

The sparks were lively and the balance of personalities was effective and harmonious. Toby’s background as a soldier was helpful in explaining Robin’s emotional state at the end of the book, and he also shared some chilling details of the destruction of Larkin’s hometown, Coventry. Liddie reflected on Larkin’s life and poetry – and she also shared a passage he wrote in a 1977 letter to her husband. The three discussed in detail the signficance of the noisy tick-tock of Katherine’s watch. But I won’t spoil it for you by quoting the end of the book, only part of the penultimate paragraph instead: