Philip Roth died Tuesday night of congestive heart failure. He was 85.

I interviewed him in February 2014, as part of Stanford’s Another Look book club celebration of the author’s 1979 classic, The Ghost Writer (see here). He had finished writing, he said, and had finished giving interviews, too. We were able to persuade him otherwise.

His weapon-of-choice was the email interview, rather than a telephone conversation. Roth was precise, nuanced and to the point. He turned around a thoughtful and polished transcript in one quick weekend. This interview was discussed in London’s Guardian here and in the Los Angeles Times here. It was republished in Le Monde‘s here, in La Repubblica here – and an excerpted version of the interview also appeared in Germany’s Die Welt here.

The Q&A, which mostly discusses The Ghost Writer, is reprinted below.

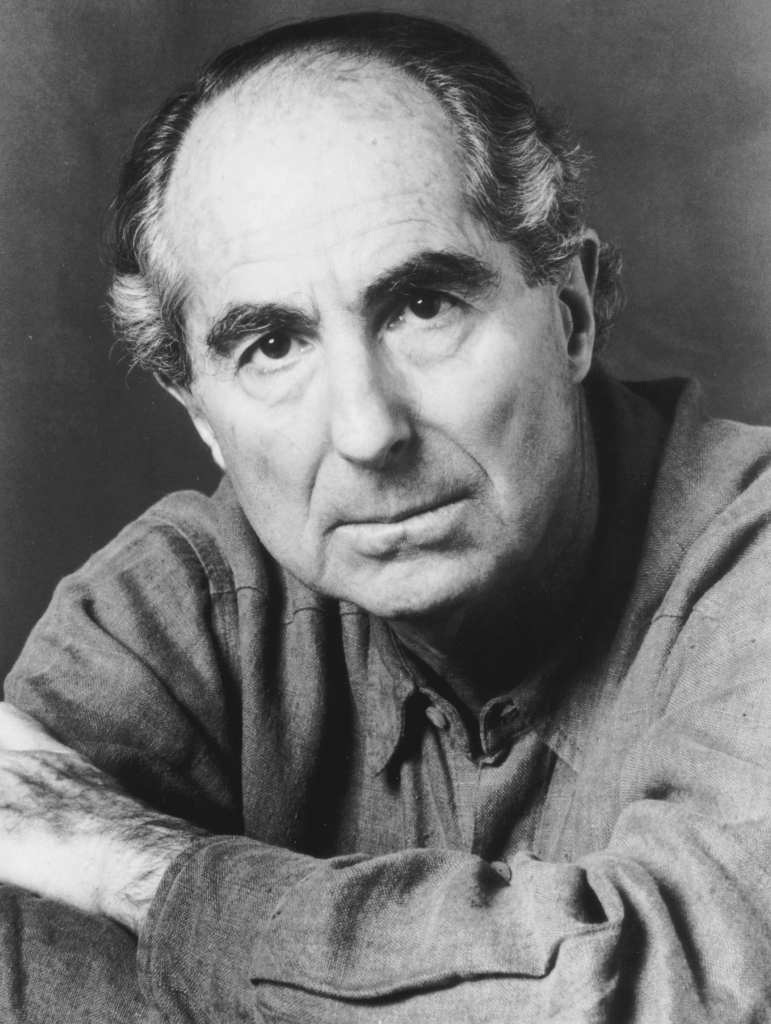

“Each book starts from ashes.” (Photo: Nancy Crampton)

Cynthia Haven: “There is no life without patience.” This thought is expressed at least twice in The Ghost Writer. Could you expand on it a little?

Philip Roth: I can expand on it only by reminding you that the six words are spoken not by me but by a character in a book, the eminent short-story writer E.I. Lonoff. It is a maxim Lonoff has derived from a lifetime of agonizing over sentences and does a little something, I hope, to portray him as writer, husband, recluse and mentor.

One of the several means of bringing characters to life in fiction is, of course, through what they say and what they don’t say. The dialogue is an expression of their thoughts, beliefs, defenses, wit, repartee, etc., a depiction of their responsive manner in general. I am trying to depict Lonoff’s verbal air of simultaneous aloofness and engagement, and too his pedagogical turn of mind, in this case when he is talking to a young protégée. What a character says is determined by who is being spoken to, what effect is desired, and, of course, by who he or she is and what he or she wants at the moment of speaking. Otherwise it’s just a hubbub of opinions. It’s propaganda. Whatever signal is being flashed by those six words you quote derives from the specificity of the encounter that elicits them.

Haven: You’ve said of your two dozen or so novels, “Each book starts from ashes.” How did The Ghost Writer, in particular, rise from the ashes? Could you describe how it came about, and your labor pains bringing it into being?

Roth: How I began The Ghost Writer almost 40 years ago? I can’t remember. The big difficulty came with deciding on the role Anne Frank was to have in the story.

Haven: It must have been a controversial choice, since she has held a somewhat sacrosanct space in our collective psychic life – even more so in 1979, when the book was published, and even more than that in 1956, when the action of your book takes place, a little over a decade after the war’s end. Were you criticized for this portrayal? How has the perception of her changed in the years since the book was published, especially given Cynthia Ozick‘s landmark 1997 essay, “Who Owns Anne Frank,” which decried the kitschification of Frank?

Roth: I could have had Amy Bellette be Anne Frank, and don’t think I didn’t put in some hard time trying to pull that off. The attempt wasn’t fruitful because, in Cynthia Ozick’s words, I did not want to “own” Anne Frank and assume a moral responsibility so grand, however much I had been thinking about bringing her story, which had so much power over people, particularly Jews of my generation –her generation – into my fiction as early as 10 and 15 years earlier. I did want to imagine, if not the girl herself – and in truth, I wanted to imagine that too, though in some way others had ignored – the function the girl had come to perform in the minds of her vast following of receptive readers. One of them is my protagonist, young Nathan Zuckerman, trying to get used to the idea that he was not born to be nice and for the first time in his life being called to battle. One is Newark’s sage Judge Wapter, watchdog over the conscience of others. Another is Zuckerman’s poor baffled mother, wondering if her own son is an anti-Semite dedicated to wiping out all that is good.

I portrayed some who, as you suggest, had sanctified Anne Frank, but mainly I decided to let the budding, brooding writer (for pressing reasons having to do both with the wound of remorse and with the salve of self-justification) do the imagining. He endeavors to forgo piety and to rehabilitate her as something other than a saint to be idolized through a close textual reading of her diary. For him the encounter with Anne Frank is momentous not because he is meeting her face-to-face but because he engages in the sympathetic attempt to fully imagine her, which is perhaps an even more exacting dramatic engagement. At any rate, that is how I solved the “owning” problem that plagued me at the outset.

Was I criticized for this portrayal? Of course there were flurries. There are always flurries. The worthy are always ready to deplore a book as the work of the devil should the book happen to take as its subject an object of idealized veneration, whether it is a historical event placed under fictional scrutiny, a political movement, a contemporary social phenomenon, a stirring ideology, or a sect, group, people, clan, nation, church that spontaneously idealizes itself as an expression of self-love that is not always shored up by reality. Where everything is requisitioned for the cause, there is no room for fiction (or history or science) that is seriously undertaken.

Was I criticized for this portrayal? Of course there were flurries. There are always flurries. The worthy are always ready to deplore a book as the work of the devil should the book happen to take as its subject an object of idealized veneration, whether it is a historical event placed under fictional scrutiny, a political movement, a contemporary social phenomenon, a stirring ideology, or a sect, group, people, clan, nation, church that spontaneously idealizes itself as an expression of self-love that is not always shored up by reality. Where everything is requisitioned for the cause, there is no room for fiction (or history or science) that is seriously undertaken.

Haven: Many consider you the preeminent Jewish American writer. You told one interviewer, however, “The epithet ‘American Jewish writer’ has no meaning for me. If I’m not an American, I’m nothing.” You seem to be so much both. Can you say a little more about your rejection of that description?

Roth: “An American-Jewish writer” is an inaccurate if not also a sentimental description, and entirely misses the point. The novelist’s obsession, moment by moment, is with language: finding the right next word. For me, as for Cheever, DeLillo, Erdrich, Oates, Stone, Styron and Updike, the right next word is an American-English word. I flow or I don’t flow in American English. I get it right or I get it wrong in American English. Even if I wrote in Hebrew or Yiddish I would not be a Jewish writer. I would be a Hebrew writer or a Yiddish writer. The American republic is 238 years old. My family has been here 120 years or for just more than half of America’s existence. They arrived during the second term of President Grover Cleveland, only 17 years after the end of Reconstruction. Civil War veterans were in their 50s. Mark Twain was alive. Sarah Orne Jewett was alive. Henry Adams was alive. All were in their prime. Walt Whitman was dead just two years. Babe Ruth hadn’t been born. If I don’t measure up as an American writer, at least leave me to my delusion.

Haven: At one point in Exit Ghost, your 2007 coda to The Ghost Writer, Amy Bellette says to Nathan Zuckerman that she thinks Lonoff has been talking to her from beyond the grave, telling her, “Reading/writing people, we are finished, we are ghosts witnessing the end of a literary era.” Are we? At times you have thought so – I refer to your conversation with Tina Brown in 2009, when you said you thought the audience for novels two decades from now would be about the size of the group that reads Latin poetry. This is about more than just Kindle, isn’t it?

Your comments were even broader in 2001, when you told the Observer, “I’m not good at finding ‘encouraging’ features in American culture. I doubt that aesthetic literacy has much of a future here.” Is there a remedy?

Roth: I can only repeat myself. I doubt that aesthetic literacy has much of a future here. Two decades on the size of the audience for the literary novel will be about the size of the group who read Latin poetry – read Latin poetry now, that is, and not who read it during the Renaissance.

Haven: You won’t be attending the Feb. 25 “Another Look” event for The Ghost Writer, which is a shame, because it’s Stanford’s effort to discuss great, short works of fiction with a wider community, bringing in guest authors as well as Stanford scholars. Book clubs have proliferated across the country. Do they offer the possibility of extending and deepening interest in the novel? Or are we kidding ourselves?

Roth: I’ve never attended a meeting of one. I know nothing about book clubs. From my many years as a university literature teacher I do know that it takes all the rigor one can muster over the course of a semester to get even the best undergraduates to read precisely the fiction at hand, with all their intelligence, without habitual moralizing, ingenious interpretation, biographical speculation and, too, to beware of the awful specter of the steamrolling generalization. Is such protracted rigor the hallmark of book clubs?

Haven: You told Tina Brown in 2009, “I wouldn’t mind writing a long book which is going to occupy me for the rest of my life.” Yet, in 2012, you said emphatically that you were done with fiction. We can’t bring ourselves to believe you’ve completely stopped writing. Do you really think your talent will let you quit?

Roth: Well, you better believe me, because I haven’t written a word of fiction since 2009. I have no desire to write fiction. I did what I did and it’s done. There’s more to life than writing and publishing fiction. There is another way entirely, amazed as I am to discover it at this late date.

Haven: Each of your books seems to have explored various questions you had about life, about sex, about aging, about writing, about death. What questions preoccupy you now?

Roth: Currently, I am studying 19th-century American history. The questions that preoccupy me at the moment have to do with Bleeding Kansas, Judge Taney and Dred Scott, the Confederacy, the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, Presidents Johnson and Grant and Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan, the Freedman’s Bureau, the rise and fall of the Republicans as a moral force and the resurrection of the Democrats, the overcapitalized railroads and the land swindles, the consequences of the Depression of 1873 and 1893, the final driving out of the Indians, American expansionism, land speculation, white Anglo-Saxon racism, Armour and Swift, the Haymarket riot and the making of Chicago, the no-holds-barred triumph of capital, the burgeoning defiance of labor, the great strikes and the violent strikebreakers, the implementation of Jim Crow, the Tilden-Hayes election and the Compromise of 1877, the immigrations from southern and eastern Europe, 320,000 Chinese entering America through San Francisco, women’s suffrage, the temperance movement, the Populists, the Progressive reformers, figures like Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, President Lincoln, Jane Addams, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, etc. My mind is full of then.

I swim, I follow baseball, look at the scenery, watch a few movies, listen to music, eat well and see friends. In the country I am keen on nature. Barely time left for a continuing preoccupation with aging, writing, sex and death. By the end of the day I am too fatigued.

Obituary at The Guardian here.

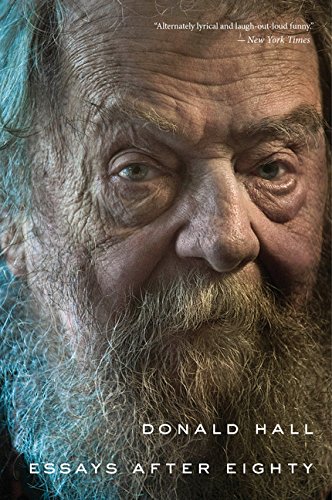

CH: You write about the fox as the totem for the writer—adhering to the convention of the writer as dangerous, edgy, shape-shifting. But aren’t most writers’ lives rather boring? I think of what Philip Roth said: “Literature takes a habit of mind that has disappeared. It requires silence, some form of isolation, and sustained concentration in the presence of an enigmatic thing.” It’s not exactly gripping stuff—which is why it’s so hard to make a good movie about writers or the life of the mind.

CH: You write about the fox as the totem for the writer—adhering to the convention of the writer as dangerous, edgy, shape-shifting. But aren’t most writers’ lives rather boring? I think of what Philip Roth said: “Literature takes a habit of mind that has disappeared. It requires silence, some form of isolation, and sustained concentration in the presence of an enigmatic thing.” It’s not exactly gripping stuff—which is why it’s so hard to make a good movie about writers or the life of the mind. CH: Let’s go back, for a minute, to Scheherazade. I can’t disagree with your comments. And yet, “storytelling” has become this all-purpose cliché for the very complicated art of writing.

CH: Let’s go back, for a minute, to Scheherazade. I can’t disagree with your comments. And yet, “storytelling” has become this all-purpose cliché for the very complicated art of writing.

Relief was near at hand:

Relief was near at hand: