Jangfeldt’s biography of Wallenberg will be out next year. (Photo: Steve Gladfelter)

Bengt Jangfeldt hesitates over the word “hero”: “I don’t particularly like to use it, it’s a cliché, but he was a hero,” he finally said. At any rate, the Swedish author won’t be able to duck the word now. The Hero of Budapest is the title of the forthcoming English edition of his biography on Raoul Wallenberg, the man who saved thousands of Jewish lives during the Hungarian Holocaust. The book should be available in February 2014.

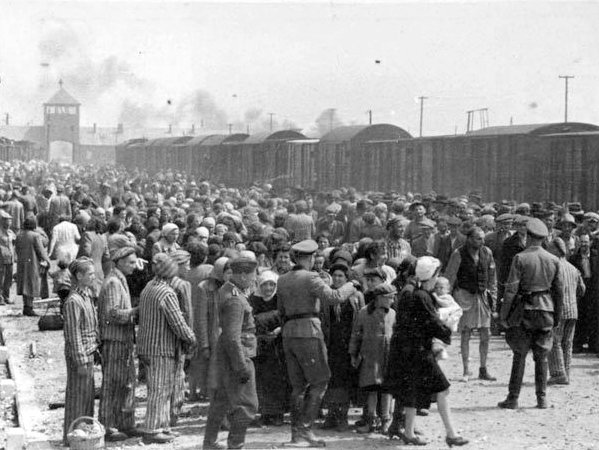

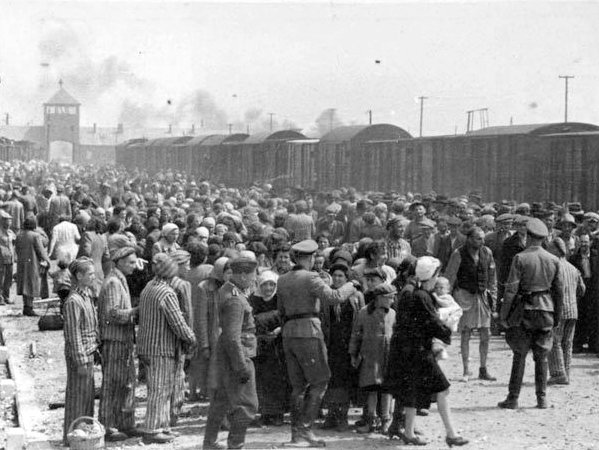

Hungarian Jews arriving at Birkenau, 1944

He spoke about Wallenberg at a late-afternoon event in Stauffer Auditorium at Hoover last Wednesday. In particular, he discussed “Swedish passivity” in responding to Wallenberg’s disappearance.

Wallenberg grew up in a wealthy banking family – akin to the Rothschilds and Rockefellers in reputation and wealth. His 23-year-old father, a naval officer, died of cancer before Wallenberg was born in 1912, and the boy was raised by his mother and a grandfather, diplomat Gustaf Wallenberg, who was as adventurous as young Raoul.

He studied in Paris and then, of all places, my own alma mater, the University of Michigan (we’ve written about that before, here) – his grandfather wanted him to attend a public university, somewhere in the heartland of America. Ann Arbor was the ticket. He took a degree in the university’s new architecture program. He also fit in time to hitchhike, drive, and bus around the country, venturing as far as Mexico. His grandfather told him it was the “best away to learn – never use your name, and never show off.”

Wallenberg in Swedish uniform

After graduation in 1935, Wallenberg took brief jobs in South Africa and Haifa, and then the footloose Swede began working for a Hungarian Jew in a import-export business in Stockholm. His boss was also part of an effort, backed by the Americans, to rescue the Hungarian Jews. Wallenberg was itching to travel to Budapest under diplomatic cover and lead the rescue operation. “It was a chance to prove to his banking family he was worthy of something. He was a loquacious, funny guy,” Jangfeldt said, “not good for banking boards, but he impressed the Americans.” He got the job.

“The Germans were increasingly dissatisfied with Hungary,” Jangfeldt said, as the Hungarians resisted their ally’s Final Solution. German tanks rolled into Budapest in March 1944 and, with the support of Hungary’s fascist Arrow Cross party, the atrocities resumed, continuing furiously even after the Soviets crossed the border a few months later. Winston Churchill wrote on July 11, 1944, “There is no doubt that this persecution of Jews in Hungary and their expulsion from enemy territory is probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world….”

Wallenberg arrived in July 1944, just as the massive deportations of over 400,000 Jews to death camps had, briefly, hit the “pause” button, soon to resume.

In Budapest, Wallenberg’s office was situated in the same building as the American Embassy. Wallenberg was daring and inventive in his efforts to save the Jews who remained, about 200-250,000 of them.

He began issuing provisional passports to any Jews who had a connection to Sweden, through business or family ties. “Suddenly, many people had ties to Sweden,” Jangfeldt said. Wallenberg, who was proud of being 1/16th Jew, recorded them all in his “Book of Life.” He may have saved as many as 8,000 Jews from deportation, but Jangfeldt emphasized that he saved many more in other ways. He provided food for the Ghetto inhabitants – “there was always food for the tens of thousands of people.” He ran networks that helped others escape or find shelter. He began a Swedish hospital in his private flat. He housed about ten thousand Jews in more than thirty extraterritorial buildings that he rented. (A denizen from one of the safe houses was in the audience at Hoover – more on that tomorrow.)

Passport photo

Using Russian and Swedish archival sources previously not available, Jangfeldt has been able to reconstruct Wallenberg’s eventual capture and death. In January 1945, Wallenberg tried to meet with the Soviet leaders on the Ukrainian front, urging them not to bomb the Jewish ghetto. Wallenberg’s Russian would have been fluent – “I know he went to my high school, and I had lots of Russian,” Bengfeldt said. It was a bad move on Wallenberg’s part.

“It’s something of an enigma why he was arrested,” Bengfeldt said. Abducting a diplomat is a violation of international law. Wallenberg was, ironically, accused of spying, or otherwise working for the Germans. Perhaps it’s not entirely a surprise; Wallenberg regularly met with top Nazi leaders, including Eichmann, and their names were in his confiscated possessions. Altruism? The Soviets simply didn’t believe it, and they didn’t believe the story about saving Jews. “From a Russian point of view, it must have been suspicious to see someone coming voluntarily to them with the story of saving Jews.”

Jangfeldt’s research revealed a startling fact: Wallenberg had at least 15 kilograms of gold and jewelry in his car when the Red Army arrested him in 1945. Again, why? Jangfeldt suggests that this was the amassed fortune of many of the Jewish victims Wallenberg had helped, who had left their valuables with him for safekeeping. He wished to return them at the war’s end to help them rebuild their lives. It seems like a reckless risk, but perhaps he had gotten away with so much, so often, that he had begun to feel invulnerable. In any case, the decision may have been the fatal one.

In April 1945, Averell Harriman, acting on behalf of the U.S. State Department, offered the Swedish government American help in making inquiries about Wallenberg’s fate. His offer was declined. Jangfeldt called this “a symbol of Swedish passivity.” The Swedes persuaded themselves that Wallenberg had been killed in Hungary – “the assumption that he had been killed in Budapest was very cynical,” Jangfeldt said. We now know he was taken to the Soviet Union’s notorious prisons, Lefortovo and later the Lubyanka.

In April 1945, Averell Harriman, acting on behalf of the U.S. State Department, offered the Swedish government American help in making inquiries about Wallenberg’s fate. His offer was declined. Jangfeldt called this “a symbol of Swedish passivity.” The Swedes persuaded themselves that Wallenberg had been killed in Hungary – “the assumption that he had been killed in Budapest was very cynical,” Jangfeldt said. We now know he was taken to the Soviet Union’s notorious prisons, Lefortovo and later the Lubyanka.

The Soviet foreign service reassured the Swedes that they had conducted an investigation, and that they knew of no one named Wallenberg in the Soviet prison system. In a sense, it may have been true. Soviet security forces operated as a state within a state, and it’s more than possible they kept secrets from their own diplomats. In fact, Wallenberg was jailed within 500 meters from the Kremlin. Throughout 1945 and 1946, Bengfeldt said that very little was done on the Swedish side – with a jaw-dropping inaction also from the banking side of the Wallenberg family, which had the power and influence to make mountains move.

Why did the Swedes turn their backs? Jangfeldt notes that a trade agreement was being negotiated between the Soviets and Sweden in March 1946. “It’s not impossible that Sweden wanted to get Wallenberg off the table for economic reasons.” Cynical? “Fifty years makes one cynical,” Jangfeldt said. Well, it’s been more than that now. One potential source of help was long gone. Gustaf Wallenberg had died in 1937 – “if he had lived, things would have been different.”

Though it’s commonly accepted that Wallenberg died in 1947, rumors and purported sightings continued into the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s. In 1989, “all of a sudden the Wallenberg belongings, from when he was arrested, had fallen off a shelf”; his address book, calendar, car registration, cigarette case, diplomatic passport and stacks of old money in a variety of currencies were returned to Wallenberg’s immediate family. His mother, stepfather, and two half-siblings never gave up hope of finding him alive. The Yeltsin era brought more transparency – access to archives and interviews – but no definitive answers. The question remains: “Wallenberg never returned home and we ask ‘Why?'”

“Russia, unlike in Germany, did not deal with its past. Wallenberg is just one of the many victims of the Stalinist terror and the Soviet regime. To understand this fact today is not very easy: the archives are still not readily available, and because of this, these books are always relevant. I think that Russia will have difficulty moving forward without such proceedings. It’s like a stone that pulls downward. For example, the recent history with ‘Memorial’ suggests that this problem still affects the life of the country.”

“Russia, unlike in Germany, did not deal with its past. Wallenberg is just one of the many victims of the Stalinist terror and the Soviet regime. To understand this fact today is not very easy: the archives are still not readily available, and because of this, these books are always relevant. I think that Russia will have difficulty moving forward without such proceedings. It’s like a stone that pulls downward. For example, the recent history with ‘Memorial’ suggests that this problem still affects the life of the country.”