Wallace Stegner, Czesław Miłosz, and what they had to say to each other

Sunday, February 7th, 2016

Stegner got used to the barbs.

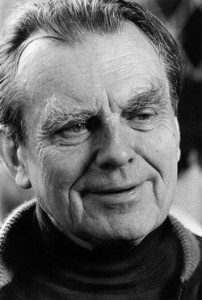

I discovered this offbeat and little-known treasure on Youtube – a rare treat for fans of American Pulitzer prizewinning author Wallace Stegner and Nobel poet Czesław Miłosz. The interview was filmed sometime in the 1980s, and has less than 1,450 views to date.

It is perhaps one of the most uncomfortable “friendly” interviews I’ve ever watched, with only occasional flashes of smiles and laughter. The unedited raw footage comes to us via Stephen Fisher Productions – with the cameramen periodically stopping the filming, interjecting questions, and restarting with calls of “Rolling!” Stegner gamely keeps trying to draw Miłosz out, as they stand on a breezy hilltop in Berkeley’s Tilden Park. They both look like they’d rather be indoors.

A reluctant Californian

The topic at hand: the effect of landscape on a writer’s spirit. “I lived through rebellion against California landscape,” Miłosz admits in his heavy Polish accent. It’s a rebellion, he said, that lasted twenty years. (I write about Miłosz as a California poet here.) Stegner agrees that California “offends a lot of people by being so dry and barren and prickly. Everything in it has barbs.” Naturally, the subject of poet Robinson Jeffers comes up on a couple occasions.

Miłosz said he missed the “cosiness” of the Lithuanian valley where he grew up – when he wasn’t traipsing about the vast expanses of Russia with his family during pre-revolutionary years (his father was an engineer of the empire). Miłosz does say that he was intrigued by the number of species he found in California – species of pines and birds and everything else. Plenty of jays in Europe, he said, but not so many as here. “I was intrigued by the essence of being a jay,” he said. Well we know what happened with that, with his poem “Magpiety.”

Watch it for yourself: