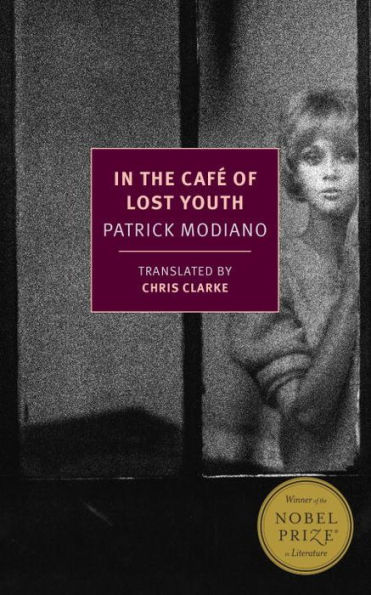

Doomed Polyxena (Lea Claire Zawada) mourns the life she will never have. (Photo: Frank Chen)

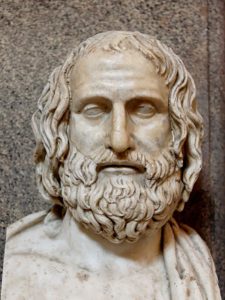

Euripides‘s play Helen is the most lyrical and tender of the playwright’s canon, and the most surprising as well. Here’s the story: Helen was never carried off to Troy by Paris; she was whisked away by the gods to Egypt to cool her heels while the Trojan War raged. (She is, after all, the daughter of Zeus … or maybe Tyndareus.) In her place, an eidolon – a specter, a lookalike, a double – went to the doomed city. Now the war is over. Menelaus is presumed dead. And the King of Egypt wants to marry Helen, twenty years older but still a humdinger. She’s clinging to a sacred shrine that offers sanctuary against his unwanted advances. What’s a queen to do?

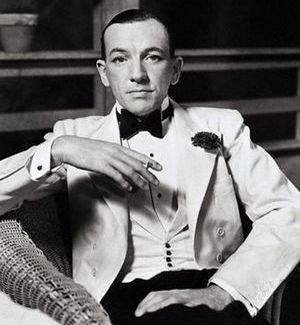

Joe Estlack as Odysseus, Polymnestor, Menelaus (Photo: Zachary Dammann)

The story has its precedents. Herodotus advanced the same tale in his Histories. And the poet Stesichorus said the same in his Palinode. But Helen – almost a romantic comedy, really, but too tinged by tragedy to make it so – is most memorably told by Euripides. Too bad it’s not told often enough. So that’s one reason to see the Stanford Repertory Theater’s current production, Hecuba/Helen, in the Roble Studio Theater. It opened last weekend and runs through August 19.

“Like the Odyssey and, even more, like the late Shakespearean romances, Helen has in some ways ‘got back to the fairy tale again,’ with its sunlit clarifications, reunions, and happy ending,” wrote poet Rachel Hadas about the play. “But its brightness is porous; plenty of suffering makes its way through. The enormous and tragic waste of the war, the pain of exile, isolation, and blame – the beauty of Helen shines through these elements without ever avoiding or denying them.”

The play is ingenuously paired with a very different offering from Euripides, Hecuba. Like the tragedian’s Trojan Women, it’s a rending, agonized lament from the female denizens of Troy, now orphaned and widowed and childless, as they are about to be hauled into slavery and worse. The threnody is interrupted occasionally by men, kings, soldiers, messengers, coming to relate the latest disastrous news or murderous decision. It’s one steady momentum downward, to Hecuba’s final revenge against her betrayer, before the Trojan queen’s descent into becoming, as prophesied, a howling dog.

African American poet Marilyn Nelson describes Hecuba as “the distillation of the pain described in the slave narratives” – “Her children dead or stolen, her husband slain, her homeland lost forever, her nobility reduced to rags: again and again, I read Hecuba’s stories in the slave narratives. Children torn from their arms and sold, lovers beaten and sold or murdered, no place to run, no place to hide, their very bodies a badge of inferiority.” And so it is.

Courtney Walsh as Hecuba, Doug Nolan as Agamemnon. (Photo: Zachary Dammann)

All the roles are doubled up, or trebled up. Stanford Rep regular Courtney Walsh revels in the exhausting challenge of playing both Helen and Hecuba – though I think her touch is made for the dark-edged comedy of Helen more.

Two men in particular give an array of arresting performances – Doug Nolan as Agamemnon a hardened soldier softened by the surprise of love. Less than an hour later he is the bullying Theoclymenus, the duped King of Egypt, alternately petulant and belligerent. Joe Estlack is the stalwart yet doubting Spartan king Menelaus – and also the oleaginous traitor Polymnestor. (He won me over when he inventively and energetically portrayed an entire shipwreck all by himself, with gurgling, coughing, spitting, and sputtering.) Props to Jennie Brick as the chorus leader and also the lippy portress-cum-bouncer at the Egyptian palace. And Stanford undergraduate student Lea Claire Zawada makes a moving and anguished Polyxena, whose life is sacrificed to the ghost of Achilles.

Thank you, sir.

The epigrammatic Greek Chorus is always a challenging convention in modern drama. Aleta Hayes‘s choreography updates the concept while hewing to its origins. It’s effective, though my own preferences run towards a plainer, less stylized interpretation, where the chorus women deliver their lines simply, singly, as lookers-on and occasional participants. The projections on the screen were more distracting than helpful, and opened the drama outward when it needed intimacy and tension.

The doubling and trebling of roles, as we watch very different characters and emotions shine through the same faces we saw minutes before, remind all of us how we each take so many roles in a lifetime – all but the best and worst of us swing from hero to villain, buffoon to sage, and back again. During Hecuba/Helen, a killer becomes lover and then a killer again, the powerful are humbled, a betrayer becomes the betrayed … and the smart-mouthed portress who kicks Menelaus away from the threshhold morphs into the benevolent prophetess Theonoe.

As the “Nevertheless, She Persisted” theme of the double show demonstrates, Euripides was an early champion of women. He was also deeply horrified by war, having lived through the long and bitter struggle between Sparta and Athens. Euripides shows both in the case of the Trojan women of Hecuba, and in Helen, which showcases a woman who been scapegoated for a war she never caused, and just wants to go home to Sparta.

Artistic director Rush Rehm translated these texts from the Greek for this production, and the final piece is stageworthy, more so, perhaps, than the more lyrical rendering of poets who have tried their hands at the task:

The gods reveal themselves in many ways,

bring many matters to surprising ends.

The things we thought would happen do not happen.

The unexpected gods make possible,

and that is what has happened here today.

Courtney Walsh (Hecuba), Lea Claire Zawada (Polyxena), and in the chorus Emma Rothenberg, Jennie Brick, Brenna McCulloch, Gianna Clark, Regan Lavin, Amber Levine. (Photo: Zachary Dammann)

Voices from the chorus: Brenna McCulloch, Amber Levine, Regan Lavin (Photo: Zachary Dammann)