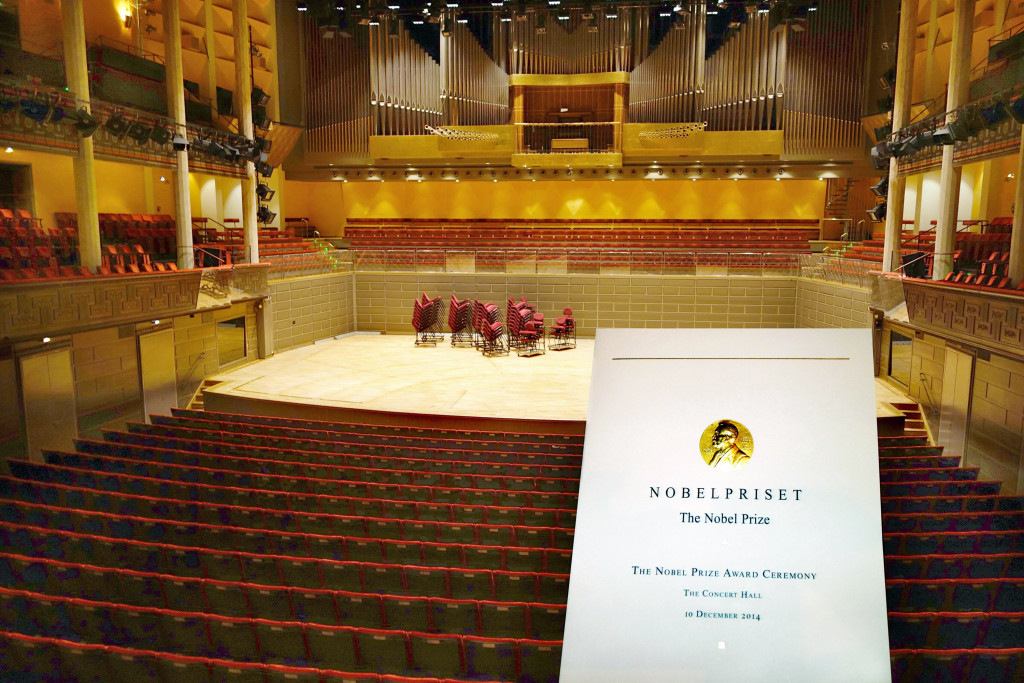

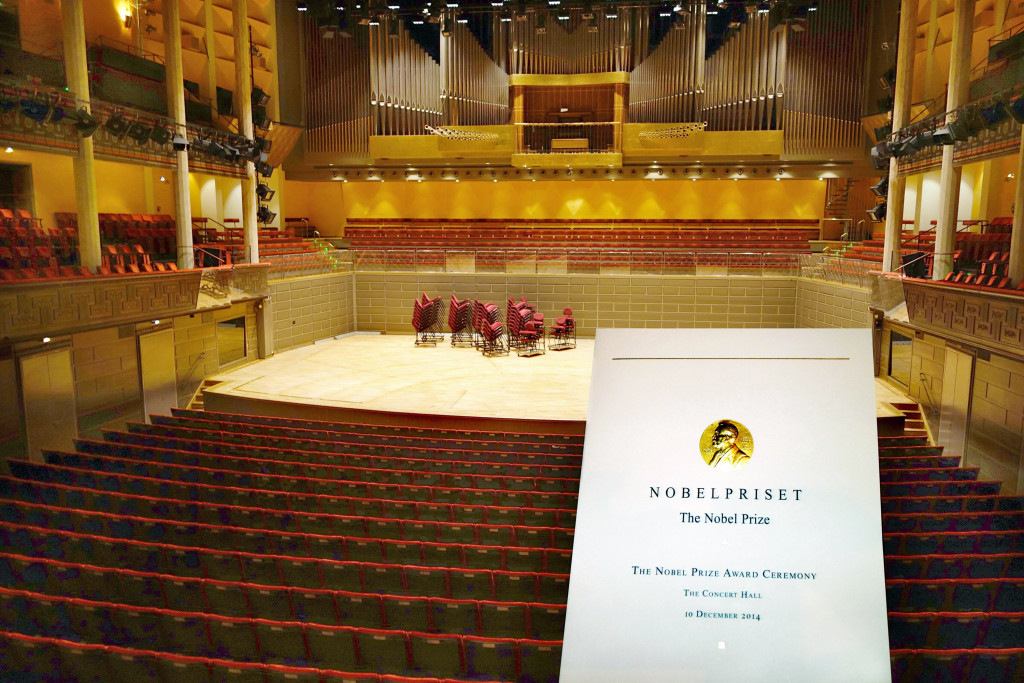

Laureates are seated onstage at the Concert Hall during the ceremony. (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

The Nobel Prize for Literature will be awarded this Thursday in Stockholm. While we await the announcement, our New York City-based correspondent, roving photojournalist Zygmunt Malinowski, reports on his recent visit to the Nobel Empire in Stockholm…

During last summer’s visit to Gdańsk for the opening of European Solidarity Center (read about it here), I found a nearby harbor with ferry to Sweden. I remembered a well-known photograph of Polish poet Czesław Miłosz dressed up in a tuxedo receiving his diploma from the king of Sweden, and I wondered what traces his visit to Stockholm might have left.

Stockholm City Hall for the Nobel banquet (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

A journey without the usual hustle of airports and cramped airplanes makes a ship seem more natural way to travel. Even though the ferry was spartan in its accommodations, it felt spacious (except for the usual closet-sized sleeping cabin). In the evening at the large cafeteria with panoramic windows, time passes slowly. One can order a coffee or something stronger and gaze at the grayish Baltic Sea and the semi-circular, unending horizon, where the distant water edge never seems to get any closer.

After about 19 hours, we arrived at the port city of Ninanshamn. From there, it’s a short rail ride on a comfortable train to Stockholm. Stockholm consists of interconnected islands; its many bridges and water taxis efficiently transport passengers on its clean waterways and canals. The historic old town (Gamla Stan) with the narrow cobbled streets and shops, restaurants, and cafés, dates back to 13th century. The neoclassical Nobel Museum, home of the Swedish Academy that nominates the literature award, is pretty much in the center of it.

Nobel ice cream at Bistro Nobel (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

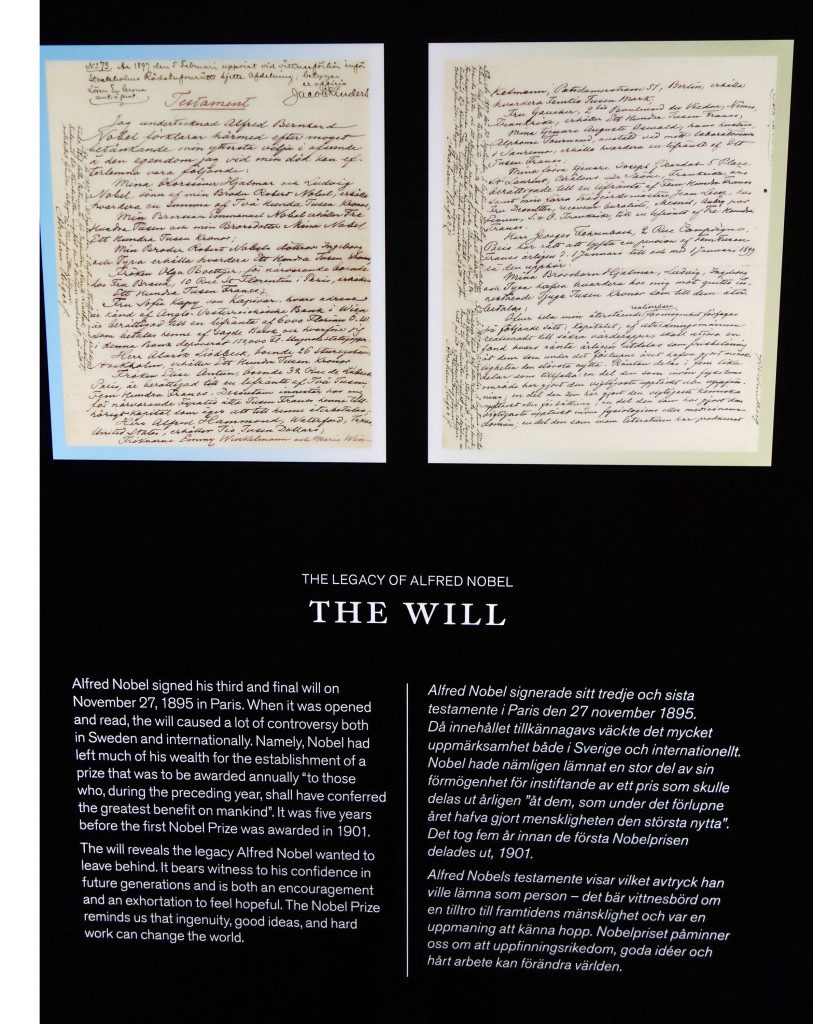

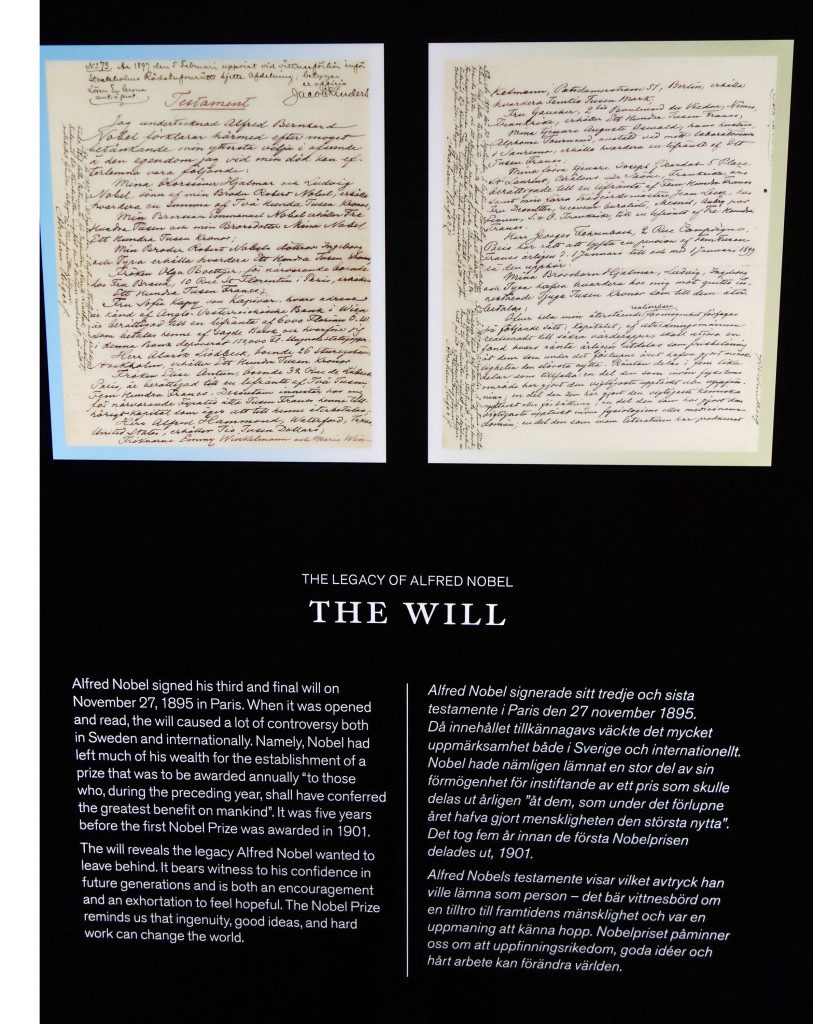

I took advantage of a guided tour offered in English. As a young man, Alfred Nobel wanted to be a poet. Inspired by Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron, he wrote all his poems in English. His father dissuaded him, saying that it was not a real job, so Alfred Nobel is remembered for inventing dynamite instead.

He also wrote several plays, but his family destroyed most of these papers, since they wanted him to be remembered for chemistry and inventions. He lived most of his adult life in Paris, never married, and had no children. His last will and testament gave away most of his fortune as annual prize. According to the museum, “Nobel was against inherited fortunes that he believed contributed to the laziness of humanity. The will was an ingenuous way of solving this dilemma. The inheritance, in the form of a prize, would reward those who have made themselves worthy by way of their work.”

Nobel had over 350 patents and made a fortune, but his idea of ideas was establishing the Nobel award in five categories: physics, chemistry, physiology and medicine, literature, and peace (later a prize for economy was added). The peace prize is awarded in Norway. Nobel met Victor Hugo in Paris, and throughout his life corresponded with Countess Bertha Von Sutter, founder of Austrian peace movement and author of Lay Down Your Arms. The latter influenced the formation of a peace prize, which she won in 1905.

The Nobel nominating process begins in September of the previous year, when the Swedish Academy committee responsible for the literature award sends out hundreds of letters to universities, institutions, and individuals qualified to nominate Nobel laureates. By the following April, the list that’s been gathered is whittled down to about 20 candidates. In May, the selection is narrowed to five candidates. The Academy becomes familiar with the proposed authors and their work. In September, the Academy finally makes a decision and the winner is announced in October. On December 10, laureates receive their prizes. The decision process remains a secret for fifty years – only now can we learn who nominated the winner from 1965.

Would you sign my chair, please? (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

The ceremony takes place in three separate locations. The laureates are invited to the Academy for lunch, on December 9, and afterwards a rehearsal. On December 10, during a ceremony at the Concert Hall they receive an elaborate calligraphy diploma and medal from the King of Sweden, in addition to a check. Attendance is by invitation only. Limos line up to take the 1,300 guests to City Hall for the banquet, first walking through the Golden Hall down marble staircase to the spacious Blue Room. In Sweden, the event is almost a holiday; it’s followed closely on TV throughout the day.

One of the highlights while visiting the museum is having lunch and Nobel ice cream with chocolate Nobel medal at the Vienna-style ‘Bistro Nobel.’ Yes, the ice cream tastes as good as it looks, and it’s actually the same dessert that was served for many years at the Nobel Banquet. Another tradition started in recent years is signing the back seat of bistro chairs. One can turn over a chair to see which laureate signed it. Signatures started after Miłosz’s visit, but I located Mario Vargas Llosa on chair #26 and Seamus Heaney, chair #23.

So where was Miłosz? See the photo below, from the central area of the museum. Also, all Nobel winners are featured on a ceiling display (also pictured below), but it would take hours to find a specific person since they are not in any particular order. I know, I waited as Samuel Beckett, Wisława Szymborska, and Madame Curie-Sklodowska, the first woman to receive Nobel Prize and first to receive it twice, rolled past, before heading for the ice cream.

.

Miłosz at last. (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

After the feast, the ball – and it takes place at the gorgeous Golden Hall. (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

Previous winner Wisława Szymborska in a rotating ceiling display at the museum. (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

The august Nobel Museum and the Swedish Academy. (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

In my end is my beginning. (Photo: Zygmunt Malinowski)

This needs to change, starting with the remarkable passage I mentioned. The scene: Our poet, Maximianus, on a diplomatic mission from Italy to Byzantium, finds himself alone with a bright young Greek thing. He falls for her, and she’s willing, but he is not the young stallion he once was. When she bewails his repeated failure to rise to the occasion, he naturally takes it personally. Whereupon she delivers a startling retort: Nescis / Non fleo privatum set generale chaos. That is (in my own translation): “You’ve missed the point. It’s not your particular condition I’m bewailing—it’s the progressive dissolution of the universe as a whole.” What for Maximianus is simply one humiliating instance of later-life detumescence is, for the rather more alert and intelligent girl, something else altogether: a moral and intellectual apprehension of universal entropy. From the failure of Maximianus’ virility she generalizes on a cosmic scale and goes on to envision, in a speech that reads like a bleak parody of Lucretius, the eventual extinction of “the human race, the herds, the birds, the beasts / and everything that breathes throughout the world,” all of which depend on the procreative impulse.

This needs to change, starting with the remarkable passage I mentioned. The scene: Our poet, Maximianus, on a diplomatic mission from Italy to Byzantium, finds himself alone with a bright young Greek thing. He falls for her, and she’s willing, but he is not the young stallion he once was. When she bewails his repeated failure to rise to the occasion, he naturally takes it personally. Whereupon she delivers a startling retort: Nescis / Non fleo privatum set generale chaos. That is (in my own translation): “You’ve missed the point. It’s not your particular condition I’m bewailing—it’s the progressive dissolution of the universe as a whole.” What for Maximianus is simply one humiliating instance of later-life detumescence is, for the rather more alert and intelligent girl, something else altogether: a moral and intellectual apprehension of universal entropy. From the failure of Maximianus’ virility she generalizes on a cosmic scale and goes on to envision, in a speech that reads like a bleak parody of Lucretius, the eventual extinction of “the human race, the herds, the birds, the beasts / and everything that breathes throughout the world,” all of which depend on the procreative impulse.