Naimark, Snyder, and Applebaum: When is murder genocide?

Friday, November 12th, 2010On one of those legendary California afternoons, full of sunshine and overlooking the magnificent San Francisco Bay, I sat on the patio of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, talking with Norman Naimark about genocide. It seemed a incongruous way to spend an afternoon in the crisp air and almost oppressive sunlight, but so it was.

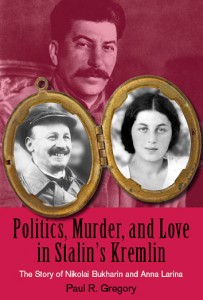

Naimark’s contention, in his controversial new book Stalin’s Genocides: We need a much broader definition of genocide, one that includes nations killing social classes and political groups. His case in point: Stalin. He argues that the Soviet elimination of a social classes (e.g., the kulaks), as well as the mass execution and exile of “socially harmful elements” as “enemies of the people” were, in fact, genocide. We miss the big picture when we treat these as discrete episodes.

I had wondered at the time, and still, about the role technology in the last century’s explosion of genocidal episodes. Clearly, incidents within archaic society — for example, the Old Testament “bans” where every man, woman, child, and even livestock were killed to remove every trace of a people — show genocidal intent. But mass communication and mass transportation have made it possible to coordinate deportation and organize killing on a scale previously unimaginable (even in Rwanda, where the weapons-of-choice were pre-tech machetes, radio was used to incite mobs and track victims) – hence the proliferation of genocide in the 20th century. Often official enablers act on a genocidaire’s momentary whim, rather than the determined aim to obliterate a people. So what does “intent” matter, under such circumstances?

I had wondered at the time, and still, about the role technology in the last century’s explosion of genocidal episodes. Clearly, incidents within archaic society — for example, the Old Testament “bans” where every man, woman, child, and even livestock were killed to remove every trace of a people — show genocidal intent. But mass communication and mass transportation have made it possible to coordinate deportation and organize killing on a scale previously unimaginable (even in Rwanda, where the weapons-of-choice were pre-tech machetes, radio was used to incite mobs and track victims) – hence the proliferation of genocide in the 20th century. Often official enablers act on a genocidaire’s momentary whim, rather than the determined aim to obliterate a people. So what does “intent” matter, under such circumstances?

The subject has come up again with Anne Applebaum‘s provocative article, “The Worst of Madness,” in the current New York Review of Books. She reviews Timothy Snyder‘s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin as well as Stalin’s Genocides. She calls Naimark’s argument “authoritative, clear, and hard to dispute.” Snyder studies the people caught between Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia, suffering two and sometimes three wartime occupations: “Between 1933 and 1945, 14 million died there, not in combat but because someone made a deliberate decision to murder them,” writes Applebaum.

She takes the notion of genocide a step beyond motive, examining how two dictators, Stalin and Hitler, played off each other in their hatred of the people in the “Bloodlands” — Ukrainians, Poles, and the Baltic states. The sum of the parts was more than the whole. The two genocidaires used a synergy of murder to kill more, and more hideously, than either nation would have done alone:

“To the people who actually experienced both tyrannies, such definitions hardly mattered. Did the Polish merchant care whether he died because he was a Jew or because he was a capitalist? Did the starving Ukrainian child care whether she had been deprived of food in order to create a Communist paradise or in order to provide calories for the soldiers of the German Reich? Perhaps we need a new word, one that is broader than the current definition of genocide and means, simply, ‘mass murder carried out for political reasons.’ Or perhaps we should simply agree that the word “genocide” includes within its definition the notions of deliberate starvation as well as gas chambers and concentration camps, that it includes the mass murder of social groups as well as ethnic groups and be done with it.”

She finally questions the whole notion of “remembering” genocide — an argument which reveals how powerfully language can shape the way we think about reality. Genocide has come to mean pretty exclusively the Jewish Holocaust, shaping and carving and in many cases eliminating from memory what happened to millions of others:

“Finally, the arguments of Bloodlands also complicate the modern notion of memory—memory, that is, as opposed to history. It is true, for example, that the modern German state ‘remembers’ the Holocaust—in official documents, in public debates, in monuments, in school textbooks—and is often rightly lauded for doing so. But how comprehensive is this memory? How many Germans ‘remember’ the deaths of three million Soviet POWs? How many know or care that the secret treaty signed between Hitler and Stalin not only condemned the inhabitants of western Poland to deportation, hunger, and often death in slave labor camps, but also condemned the inhabitants of eastern Poland to deportation, hunger, and often death in Soviet exile? The Katyn massacre really is, in this sense, partially Germany’s responsibility: without Germany’s collusion with the Soviet Union, it would not have happened. Yet modern Germany’s very real sense of guilt about the Holocaust does not often extend to Soviet soldiers or even to Poles.”

“Finally, the arguments of Bloodlands also complicate the modern notion of memory—memory, that is, as opposed to history. It is true, for example, that the modern German state ‘remembers’ the Holocaust—in official documents, in public debates, in monuments, in school textbooks—and is often rightly lauded for doing so. But how comprehensive is this memory? How many Germans ‘remember’ the deaths of three million Soviet POWs? How many know or care that the secret treaty signed between Hitler and Stalin not only condemned the inhabitants of western Poland to deportation, hunger, and often death in slave labor camps, but also condemned the inhabitants of eastern Poland to deportation, hunger, and often death in Soviet exile? The Katyn massacre really is, in this sense, partially Germany’s responsibility: without Germany’s collusion with the Soviet Union, it would not have happened. Yet modern Germany’s very real sense of guilt about the Holocaust does not often extend to Soviet soldiers or even to Poles.”

The implications of her reading are many: For the U.S., World War II was the “good war,” against all the ambiguous or “bad wars” that followed—Vietnam, Iraq, Korea. For Americans, WWII begins with Pearl Harbor and ends with the atomic bomb. But Western peace was won by selling out whole nations to our murderous ally. “This does not make us bad,” writes Applebaum, “there were limitations, reasons, legitimate explanations for what happened. But it does make us less exceptional. And it does make World War II less exceptional, more morally ambiguous, and thus more similar to the wars that followed.”

And for Western Europe: “When considered in isolation, Auschwitz can be easily compartmentalized, characterized as belonging to a specific place and time, or explained away as the result of Germany’s unique history or particular culture. But if Auschwitz was not the only mass atrocity, if mass murder was simultaneously taking place across a multinational landscape and with the support of many different kinds of people, then it is not so easy to compartmentalize or explain away.”

Postscript on 11/15: Speaking of genocide… “On Wednesday, al Qaeda militants launch a synchronized bombing attack on 11 Christian communities throughout Iraq, killing six and wounding more than 30. That attack followed on the heels of the ghastly assault last month on Christian worshippers attending a service at Our Lady of Salvation church in Baghdad, in which 58 people were brutally murdered and another 60 wounded. … the Iraqi government has done absolutely nothing to protect the besieged Christian community from further attack, despite a promise from al Qaeda in Iraq that ‘all Christian centers, organizations and institutions, leaders and followers, are legitimate targets for Mujahedeen wherever they can reach them.’ Americans of all faiths must band together and pressure the State Department to do something about the wanton murder of Iraqi Christians before there are no more Christians in Iraq to protect.” At the Daily Beast here.

Norm Naimark makes his case in the video below: