From Troy to the Caribbean: Homer onstage

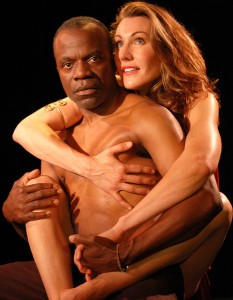

Wednesday, July 21st, 2010Last year, during the Stanford Summer Theater’s Electra by Sophocles, one performance stood out remarkably in the mixed bag of university theater. L. Peter Callender played a role that might have been negligible for a less accomplished performer. The faithful family retainer, in this case a tutor, is a staple in Greek tragedy, but Callender infused it with dignity and distinction.

I’m not the only one who noticed him last year: A San Francisco Chronicle review praised his performance in Athol Fugard’s My Children! My Africa!, a play that some consider too persistently didactic, although in this production “one dedicated teacher’s tragedy is a fierce reminder of the complexity of trying to right social wrongs. L. Peter Callender embodies that complexity with every paternalistic utterance and sidelong glance he casts as the prematurely aging black teacher,” Robert Hurwitt wrote.

He’s back. I sat in on some of the rehearsals for a few weeks ago for the Stanford Summer Theater’s Homeric cycle, which showcases The Wanderings of Odysseus, an adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey, opening Thursday night. It was the second year of the Greeks, but not for Callender, who has performed Greek tragedy for years, everywhere from his alma mater (Julliard) to Berkeley Rep.

“It’s one of my favorite types of theater when it’s done well,” he told me later by phone, “because of the language, because of the history, the mythology, the depth of character and the depth of passion.”

But he admitted, “I’m finding a lot of this very difficult to memorize.”

No surprise. His work with Shakespeare (he’s logged in a couple dozen Shakespeare roles in the California Shakespeare Theater alone) has given him a feel for the iambic beat of the Bard’s blank verse — the beat that mimics the rhythms of the heart. Oliver Taplin’s translation of The Odyssey, which Rehm directed for the Mark Taper Forum in 1992 at the Getty Museum, uses a loose Anglo-Saxon prosody – a quicker four-beat line that’s dependent on a lot of alliteration and a big caesura in the middle of the line (think of Seamus Heaney’s bestselling Beowulf.) It’s a bit of a rhythmic (and therefore psychological) shakeup.

During the rehearsals, Callender joined Rush Rehm in making suggestions for the fine detail work of the challenging production. ”This text is not a play but a poem, it’s a very difficult task. Everyone has to be on the same page at the same time,” he said.

His self-confidence in the director’s chair isn’t a surprise, either: he’s the founding director of San Francisco’s African American Shakespeare Company, launched in 1994 to “create an opportunity and a venue for actors of color to hone their skills and talent in mastering some of the world’s greatest classical roles; and to unlock the realm of classic theatre to a diverse audience who have been alienated from discovering these time-favored works in a style that reaches, speaks, and embraces their cultural aesthetic and identity.”

The “L.” at the front of his name was a sort of augury for things to come: It stands for “Lear.” (In answer the inevitable follow-up question, he replies, “I don’t know what my parents were thinking.”)

The Trinidad-born actor will probably excel also at the August 10 and 11 reading of Derek Walcott’s Omeros – which takes place in the poet’s native Saint Lucia. It will return Callender to blank verse, as well as combining his love of the Greeks and his Caribbean heritage. I was recently reading Irena Grudzińska Gross‘s comments on the Nobel poet:

Instead of history, which is degrading and calls for revenge, Walcott proposes a narrative, or a myth, which, because of its continuous present, opens time, making the new world equal to the old one. His long poem Omeros show that the world of the Caribbean islands is as epic as Greece, because it contains a journey, a return to the native island, the fear of ancestors, gods.