Timothy Murphy may be the most prolific lyric poet in English ever – and he’s dying.

Friday, June 15th, 2018

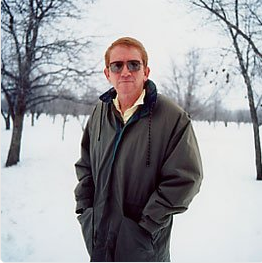

Tim in North Dakota

Update on June 30: Tim Murphy’s last email to me said that we would talk when he got over his thrush, which made conversation difficult. “Hell of an affliction for a poet,” the Dakota poet added in an email on June 2.

His body was riddled with what he called “six warring cancers.” Then he broke his hip, too. I tried calling some time later, and he said, “I am in agony.” A few days ago, his family had silenced his phone and were not answering messages. “There are scores of unanswered emails. His family is deluged,” wrote Jennifer Reeser, who, as his executor, says she is now “Tim’s agent on earth.” He died in his home in the early hours this morning – peacefully, she says. I don’t doubt it. He had earned it.

His Last Poems? was 168 pages long when he sent it to me in mid-May, but had grown to some 230 pages by the time we last communicated – he said he’d send it. He signature line: “so yes, I’m writing better and faster than I ever have. fondly, Tim”

Tim Murphy is dying and he knows it. He received the news on January 10, his 67th birthday. Now the poet is in advanced stages of cancer at his North Dakota home, and he is writing quickly, feverishly, fiercely, a poem or two a day, despite physical limitations, heavy medications, and overwhelming setbacks. He is racing against extinction.

North Dakota State University Press is preparing to issue a Collected. It’s a daunting effort: his fourteen collections total something like 1,400 pages. “That makes m e the most prolific lyric poet in English,” he crowed in a recent email. His Last Poems collection followed his diagnosis (the version I have totals 168 pages) and describes his grim predicament, its origins and inexorable destination:

e the most prolific lyric poet in English,” he crowed in a recent email. His Last Poems collection followed his diagnosis (the version I have totals 168 pages) and describes his grim predicament, its origins and inexorable destination:

Owning It

Family history is just so clean

cancer never intruded on my thought.

I’ve hunted hard each fall, I’m whippet lean,

but my twin vices have been dearly bought.

My brother Jim embraced a grimmer view:

“No Murphy ever drank and smoked like you.”

We met at the West Chester Poetry Conference, at the turn of the century, and kept up a sporadic correspondence. I published a long Q&A with him, and I still think it reads rather well. He did, too, when he recently reread it. From my introduction:

Timothy Murphy, all dressed up.

Photos don’t do him justice. Tim Murphy is harder, leaner, smaller, and more prominently beaked than any news photographer has caught to date. Moreover, his brilliant red hair, set off by a welter of freckles, softens to a dull, inexpressive gray in newsprint black-and-white. Face to face, Murphy brings to mind a fierce, small hawk over the North Dakota wheat fields of his native Red River Valley.

In addition to being a poet of note, Murphy is also a venture capitalist and partner in a farm that produces 850,000 hogs a year. “I do the dirtiest, most difficult job on a farm,” he often quips to reporters. “I borrow the money.”

His poems have received kudos from high sources, including Pulitzer prize-winning poet and former U.S. Poet Laureate Richard Wilbur, who praises Murphy’s wide learning, the elegance of his writing, and his “extraordinary conversancy with a lot of the poets of the past, in many languages.”

“Tim uses rhyme and meter in a songlike way––which a great many modern poets have forgotten how to do. Most poets nowadays are not lyric in that sense. Tim writes poems that a composer could set to music,” says Wilbur. Moreover, “his poetry is lucid. When he is subtle, it’s the kind of subtlety that leads you into understanding. He uses forms without showiness and always with a point.”

At Yale University, where Murphy was Scholar of the House in Poetry, he studied with Southern agrarian poet Robert Penn Warren (another Pulitzer prize-winner and former poet laureate), who had grown up on a Kentucky tobacco farm.

Warren, however, refused to give him a recommendation after Yale. Murphy was courting the East Coast literary world and aiming for a poet-in-residency at a prestigious academy. “I needed to cultivate the sense of place which I so fervently admired in Yeats, Hardy, and Frost, but which I had not yet found in the land of my own birth,” Murphy wrote in Set the Ploughshare Deep. “Go home, boy,” Warren had told him. “Buy a farm. Sink your toes in that rich soil and grow some roots.”

Richard Wilbur and “Charlee” were friends.

Murphy took the advice. Twenty years later, he published The Deed of Gift (Story Line Press, 1998). During the intervening two decades, he distilled his blowsy iambic pentameter narrative lines to the briefest of dimeters and trimeters, often in poems of a dozen lines or less.

The openly gay Murphy describes himself as a “Faggot Eagle Scout Libertarian Factory Farmer Carnivore Poet.”

Well, read the whole Q&A over at the Cortland Review here.

His story didn’t end there. Alan Sullivan, his beloved friend, as well as editor, translator, and collaborator, succumbed to cancer seven years ago. Both underwent late-life conversion experiences. I haven’t had a chance to read thoroughly and thoughtfully the manuscript Tim sent me a few months ago, but I flagged this as a personal favorite, having met the late great poet Richard Wilbur and his wife “Charlee” at that same West Chester Poetry Conference, seventeen years ago (Pistis, elpis, agape – St. Paul’s faith, hope and love):

Prayer to Charlotte Wilbur

Your death day Holy Tuesday, Charlee, pray

. hard for your “young” friend

. facing a painful end,

chemo and radiation. Day by day

I trudge to treatment, trailing my slender hope,

. wishing only to write.

. Burdened, I wake at night

weighed by an anchor eye-spliced to a rope,

symbol of elpis. Pistis, agape too,

. with these must I surround

. my soul and stand my ground,

trying to die unbowed. I pray to you,

much cherished matron in the Heavenly Host.

Put in a warm word with the Holy Ghost.

Postscript on July 1, from poet and translator A.M. Juster on Twitter: