Out of the shadows: C.S. Lewis in Oxford

Saturday, December 3rd, 2011In the summer of 2009, I visited C.S. Lewis‘s digs about two miles outside Oxford. Having seen Shadowlands, the movie based on his life (it must have been filmed somewhere else), I must say I was expecting something a little grander. Not grand, just grander.

I knew the author had never been rich, but I wasn’t expecting a place quite so cramped and makeshift, quite so… well … “adequate.” But what struck me most on the personal tour is how William Nicholson‘s play and subsequent film misrepresented a life that was not a passionless, solitary bachelorhood, but crowded with people and noise and human obligations, whether to the bad-tempered mother of a dead friend who lived at Kilns with him and his alcoholic brother, Warren, or the rotating tribe of teenage wards who came to crowd the quarters.

Some of the obligations were self-imposed. As Tom O’Boyle wrote recently in the Pittsburg Post-Gazette:

One discipline he kept as a result was replying to the 20-30 letters he received each day from fans on the day of receipt. It’s estimated he wrote as many as 20,000 letters during his lifetime. Maintaining this practice consumed hours every day and was especially taxing as his health began to fail.

I reviewed the 1,800+ page third volume for the Washington Post here, and mentioned the same. Lewis wrote everyone, including T.S. Eliot, the sci-fi maestro Arthur C. Clarke, and the American writer Robert Penn Warren. “Other letters were from cranks, whiners and down-and-out charity cases; he answered them all,” I wrote.

“’The pen has become to me what the oar is to a galley slave,’” he wrote of the disciplined torture of writing letters for hours every day. He complained about the deterioration of his handwriting, the rheumatism in his right hand and the winter cold numbing his fingers. In the era of the ballpoint, he used a nib pen dipped in ink every four or five words.”

“’The pen has become to me what the oar is to a galley slave,’” he wrote of the disciplined torture of writing letters for hours every day. He complained about the deterioration of his handwriting, the rheumatism in his right hand and the winter cold numbing his fingers. In the era of the ballpoint, he used a nib pen dipped in ink every four or five words.”

For me, Jack Lewis is the patron saint of labor. And the turning point was a warm September night in 1931, when he took an after-dinner walk with Oxford chums Hugo Dyson and J.R.R. Tolkien. The three strolled on Addison’s Walk, a beautiful tree-shaded path along the River Cherwell (I’ve walked it often on my Oxford visits), and got into an argument that lasted until 3 a.m. It resulted in his conversion.

As O’Boyle put it:

The effect of this conversion was explosive. Before it, Lewis’ ambition to be a great writer had been hampered by the fact that he hadn’t found anything worthwhile to say. The ledger of pre- vs. post-conversion literary output is hard to fathom. Pre: two slim volumes of verse; post: a torrent of books, essays, novels and radio talks – more than 30 published titles – all works with obvious Christian themes.

After conversion, he also prodded Tolkien to pull together and complete his tales about the private universe that had preoccupied him … Middle-earth.

Two slim volumes of verse. A couple decades ago, at least, I remembering sitting on a sunny afternoon on a balcony outside a small library, idly thumbing through a volume of C.S. Lewis‘s poetry. The magical lightness, the imaginative leaps, the quicksilver sense of the miraculous everywhere which colors Till We Have Faces, The Space Trilogy, The Great Divorce, and the Narnia books was nowhere to be found.

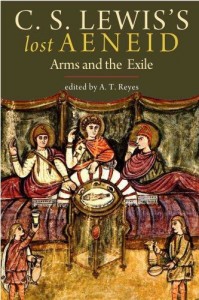

As I recall it, the poems had the solid, leaden consistency of a bowl of porridge. So I was eager to alter my opinion with his recently published fragments of Virgil‘s Aeneid, a translation project that was interrupted by his death, the same day that John F. Kennedy was shot, Nov. 22, 1963. I haven’t had time to give it a fair shake, but I haven’t seen much to change my mind.

In Books and Culture, Sarah Ruden agrees. She wrote that, in his preference for archaic language and stilted locutions in his poetry showcase “Lewis at his narrowest.”

I know the narrowest (he disliked not only Eliot’s verse, but Evelyn Waugh‘s prose), but find virtues that more than offset them in the man as well as in the prose. (Besides, people say the same about Jane Austen – and really, isn’t that’s one of the reasons she’s delightful?)

Steve King, in a Barnes & Noble review, “Remembering C.S. Lewis,” on Lewis’s Nov. 29 birthday last week, recalled his prodigious memory: “Meetings often lost focus as Lewis galloped through whatever books, ideas, allusions, and quotations sprang to mind. Few could keep up on the scholarly ride,” though others found it great fun. According to his student Alastair Fowler:

Lewis has been called “bookish” — a dumbed-down response. Of course he was bookish; hang it, he tutored in literature. Even standing on the high end of a punt in a one-piece swimming costume with a single shoulder strap, about to dive, he had time for a quotation….”

And maybe there is even something to be said for “Lewis at his narrowest.” From Fowler again:

He had been laughed at for offering himself as a specimen of Old Western culture. But he proved in actuality to be one of the last of a threatened species. Before he died, he wrote, optimistically, of the tide turning back to literature. In the event…[u]niversities submitted to bureaucratic management, dons morphed into accountants, training replaced education, and Theory displaced literature. Reading simplistic codes, supplying false contexts, pursuing irrelevant indeterminacies or tell-tale “gaps”: these have proved no substitute for the memorial grasp of literature.

A belated happy birthday, Jack.