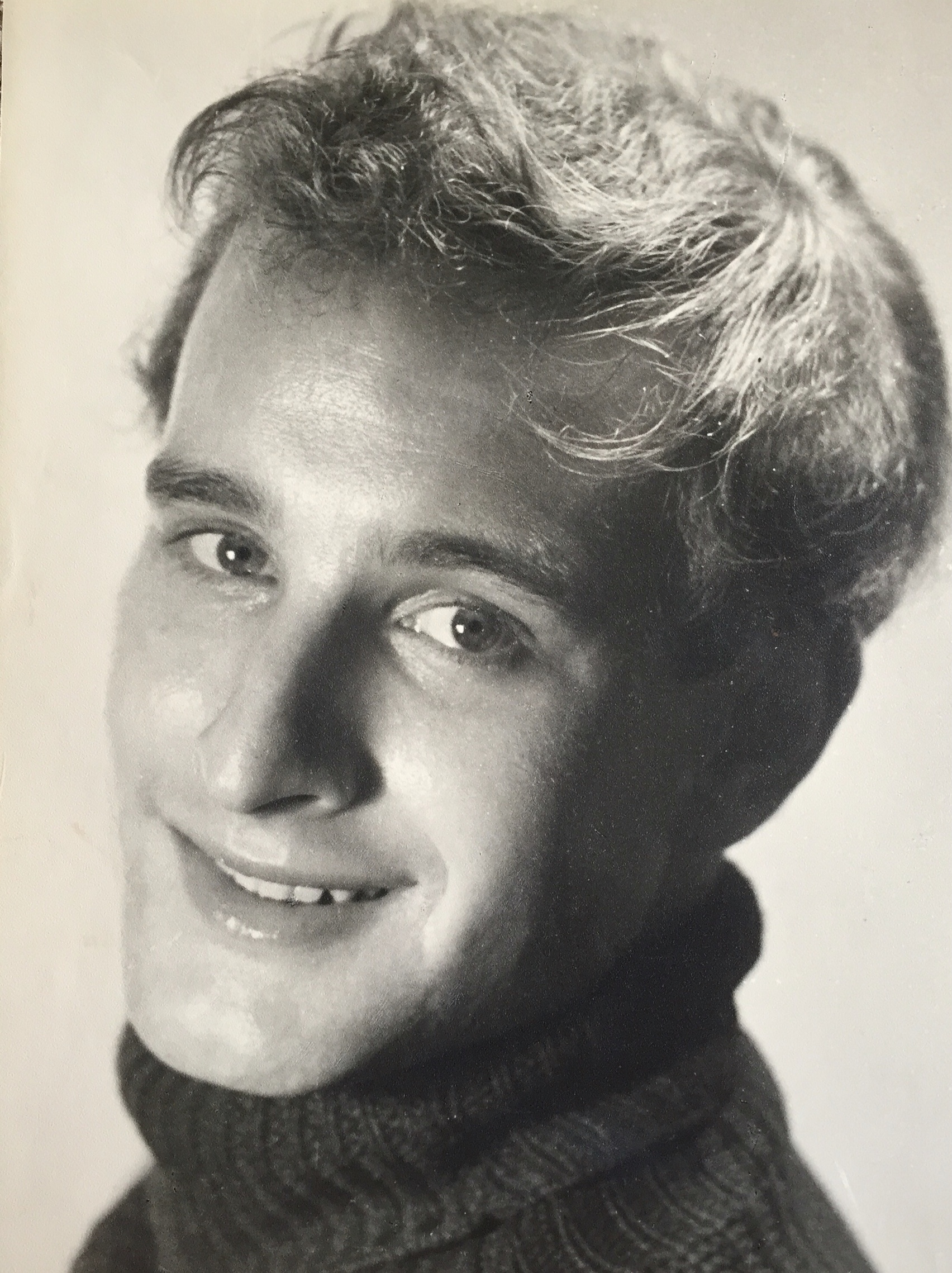

Harry Elam, Marina Lewis, and Florentina Mocanu. (Photo: David Schendel)

Last week, Stanford friends, colleagues, students, and former students gathered at the Roble Studio for the memorial of the eminent German director Carl Weber, a former protégé of Bertolt Brecht and emeritus professor of drama, who died on Dec. 25 at 91 (we wrote obituaries here and here). The occasion followed the Carl Weber lecture, an annual event that began about five years ago. Plenty of pinot noir (Carl’s favorite varietal) was tipped to commemorate the passing of one of Stanford’s internationally renowned giants – thanks to Branislav Jakovljevic, chair of Stanford’s Department of Theater and Performance Studies, who organized the event.

Branislav Jakovljevic with pinot noir. (Photo: David Schendel)

“Professor Carl Weber was a humanist whose exquisite knowledge of life, theatre and history was inspiring and daunting at the same time,” said the Romanian director and actress Florentina Mocanu-Schendel, a close friend and former student. “He lived, learned, told and retold stories with the enthusiasm of a beginner, generous, kind, and discreet – never betraying his immense experience – he encouraged us to live, practice, write with courage and humor, and always challenged us to express our vision. His question reverberates: What do you see? We know that Carl saw the world with his entire being.”

At the request of Carl’s daughter Sabine Gewinner-Feucht, she read a 1938 Brecht poem, “Legend of the Origin of the Book of Tao Te Ching on Lao Tsu’s Road into Exile.”

A statement from Stephan Dörschel, head of Berlin’s Archive of Performing Arts, also lauded the late director. Here it is:

“In April 2012, I met this man, small in stature but with an enormous past – director, professor, dramaturge Carl Weber. We spent four days at Stanford University researching his artistic-scholarly and biographical archive, preparing all the documents for the transport to the Archive of Performing Arts – Academy of Arts, Berlin. These were four intense, activity packed days, in which I found out about his theatre beginnings in the POW camp with Klaus Naschinsky, later famously known as Klaus Kinski. I learned about Carl’s work with Bertolt Brecht and his rehearsal methods, about his response to the Berlin Wall and GDR in 1961, and his exile to the USA, where he became the ambassador of German theater in New York. With his professorship at New York University and Stanford University, Carl was able to share his knowledge but also discover and promote young talents: he was incredibly proud of [his former student] Tony Kushner. Professor Carl Maria Weber was remarkable and his work will be immeasurably influential in the future. I bow with great admiration and affection before him!”

(The Carl M. Weber-Archive can be accessed at the Academy of Arts, Berlin, here.)

Others shared their memories of this extraordinary man. Here are a few of them:

Harry Elam recently appointed vice president for the arts and senior vice provost for education, is a scholar of theater and performance studies. He recalled the moment Carl spat and playfully shouted, “Toi! Toi! Toi” – “which I first didn’t understand at all what we was doing and seeing my confusion, he explained that it was the German version of ‘break a leg.’” An excerpt of his remarks:

Harry Elam and Aleta Hayes, dance lecturer (Photo: David Schendel)

Carl Weber epitomized the conjunction of theory and practice that has come to serve as the central conception of the Theatre and Performance Studies at Stanford. Carl not only understood but exemplified how the study and analysis of theatre and performance informs and is informed by the practice of theatre. Carl embodied what it meant to be a scholar/artist. An esteemed scholar and translator, one of the foremost interpreters of Bertolt Brecht, credited with bringing the work of the Great East German playwright Heiner Muller to English speaking audiences, Carl exercised and promoted the critical import of intellectual engagement with the dramatic text. …

Yet the Carl Weber who came to be towering presence in this department, whose powerful shadow and profound accomplishments still fill our hallways, was never self-promoting but always self-confident. He was at times strong willed and yet was also always open to the differing perspectives. He gave generously of his time and his artistry but also remained guarded in his criticism, finding the right time and productive ways to express concerns. Carl was indeed a special soul that has made an indelible impression on this department, on this institution, and on our theatrical world. … there was no playwright he didn’t know or play he hadn’t read, directed, or seen. So, when I talked within him about contemporary playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, he knew the work, and brought deep insight and analysis to our discussion. …

Carl kept teaching well until his eighties, because he loved it, because it kept him young and Carl always had a young and inquisitive soul. And he influenced so many, from the undergrads who took his sophomore seminars on Brecht, to many of those in this room who where his grad students, to the famous story of Tony Kushner and how he thanked Carl for his impact on his career and the list goes on. Last November, Stanford parent, film star and Bay Area native son, Tom Hanks came to Stanford and performed in a benefit along with wife Rita Wilson for Stanford. Afterward, he talked about what influenced him to go into acting … and he mentioned as a student coming across the bay on a class trip to see a production of Brecht over at Stanford. He vividly described the production and confided that was so moved by the production, so impacted by the theatrical experience that he determined then and there that this is what he wanted to do, to act. Of course, the play he saw was staged by Carl Weber. Indeed, there was no one like Carl Weber. Rest in peace, Carl.

Michael Hunter (co-founding artistic director of San Francisco’s new theater company Collected Works) is a director, performance curator, and adjunct professor at Stanford University, where he received his PhD in Drama and Directing. Excerpts from his remarks:

Carl in his Stanford office, 2004 (Photo: Daniel Sack)

His commitment to passing on knowledge was so deep, and he was so tireless in his energy and willingness to support and critique our work – and the two things go hand in hand: one of the main reasons his critiques were so helpful was because he was also so present and steadfast in his support of his students.

I think one of the biggest things Carl taught me has to do with the seriousness of theatre, as a tool that can shape the world. One of the reasons I came to Stanford was to work with Carl: as an undergraduate, I was very seduced by Brecht, and by the idea of theatre as a political tool, and also by the notion of the director-scholar. I remember reading Carl’s conversation with Tony Kushner about Brecht while I was flying from Edinburgh to Texas, and feeling strongly that I wanted to work with, and learn from, this man.

I also remember starting to take directing classes with Carl shortly after I arrived, and like many of us, being kind of frustrated because we spent all of our time talking about what we saw, in such intense detail. I found it a little pedantic – I was in a PhD program at Stanford! Where was the meat? And like many of Carl’s students, I look back on that training as one of the most important things that happened in my development. Carl taught me to look in a way I had never done before, in a completely patient, tireless way. That man could sit and look at something for hours and hours and his attention would not flag – and he would probably tell you later that it was too long, but that would never stop him from watching it with his full attention.

I guess another word for this would be rigor – the rigor of thought, the rigor of deep, sustained attention, and the rigor of history. Of course the undergrad in me agreed that theatre could be a tool to make change, but it wasn’t until I saw how seriously Carl treated theatre – treated dramaturgy, treated casting, treated rehearsals – that I understood that immensely hard work was required to make it a tool. It didn’t just happen; in fact, 95% of the time it doesn’t happen. But Carl taught us all not to cut corners, to work and work and work until we had reached precision, and to know our history.

Michael Hunter (Photo: Marina Lewis)

Of course I’ve never met anyone who knew, and remembered, his history like Carl. Even the last time I visited with him, he was discussing the origins of the First World War, and he never lost that historical memory. In his dramaturgy class, when I flirted with the idea of using Brecht’s The Days of the Commune for my quarter long project, I was daunted by the double task of researching both the period of the commune itself and the post-War context in which Brecht wrote it – knowing that Carl would not let me by with short-changing either history. He was baffled that I would shirk form the challenge – for him, there was no more exciting project than one in which two historical periods would be held in tension, looked at from the third vantage of the contemporary. …

I ended up helping Carl take care of was going through his home library, and figuring out where his incredible and eclectic library – of novels and plays and history books, and the theatre journals he had collected for decades – should go. I spent weeks in that library, and I was struck initially, and most obviously, by the range of Carl’s erudition. But his collection of plays in manuscript form also brought home to me how much he had been a champion of the experimental language playwrights of the 1970s and 80s – Mac Wellman and Peter Handke especially. I remembered that this side of Carl had seemed remote to me when I first started taking classes with him – how could a man who seemed attached to concrete detail in such a literal way also have made it his work to produce these wild, anarchic assaults on logic and convention? And the lesson really came home for me that it was precisely his rigorous attention to the concrete that made it possible for him to produce this kind of work – that creating worlds that are not merely a mirror of our own requires even more effort to be precise about what people are seeing. And that in order for true experiment in the theatre to “work,” as Carl would put it, abstraction always has to be undergirded by a great commitment to the detail.

Marina Lewis was a Stanford neighbor and friend for nearly thirty years. She offered some remarks on the private side of Carl:

Harry Elam and Marina Lewis (Photo: David Schendel)

He usually did the shopping – and time and again, at least once a week, I saw him bringing home a bouquet of flowers to Marianne, whom he adored. He was a very romantic fellow. They frequently traveled to France where they had a – so I have heard – lovely home in the countryside.

After Marianne suddenly passed away in France about ten years ago, he came back a broken man. All he could think about was Marianne and that she did not come home with him.

Then, as usually happens, time has a way of healing wounds. He had resumed contact with many of his colleagues and friends in Germany especially after the Fall of the Wall, and after one such trip I saw him coming back with a very attractive woman accompanying him. Of course I was curious and looked forward to meeting her. Her name is Inge [Heym] and she was, as I heard later, the mother of Charlie’s son Stefan. It was a passionate but brief courtship, but at the time, circumstances did not permit for them to stay together. Now, later in life, each having lived their own separate lives, they rekindled that once upon a time love affair which lasted to the day Charlie died.”

Marina Lewis, who is Austrian, has continued her friendship with Inge Heym and with Carl’s daughter Sabine, who lives in Austria. She shared this message from Inge Heym with the gathering:

Professor Carl Weber, a true friend, a good human being, has recently left us. To his many friends in Berlin, Charlie, as he was known, will remain a fond memory. Those friends shared with him the good times in the 1950s when he was an assistant of Bertolt Brecht in the Berliner Ensemble.

He had come to East Berlin from Heidelberg and was quickly drawn into the literary and artistic Boheme in the GDR. In 1961, when the Berlin Wall was built, Charlie stayed on the other side and our contact grew infrequent. And soon after he left for New York.

Our contact never ceased totally, however. His friends knew and valued his work and missed his presence.