“Notoriously tricky territory”: Elizabeth Conquest on the literary legacy of Robert Conquest, a long marriage, and lots of letters

Sunday, April 22nd, 2018

A marriage that was a “long conversation” … and plenty of papers, too. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

We’ve written about historian and poet Robert Conquest before – most notably for the Times Literary Supplement here, but also here and here and here, among other places. About his widow Elizabeth Conquest – a.k.a. “Liddie” Conquest – we’ve said comparatively little. That’s about to change. She will be one of the panelists at the Another Look book club on Monday, April 30, discussing Philip Larkin‘s early novel A Girl in Winter. But you might also turn to the pages of the Tunku Varadarajan‘s article in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal, titled: “The widow of historian and poet Robert Conquest talks about his legacy – which includes three books still forthcoming”.

Liddie Conquest in London.

Robert Conquest was the first historian to chronicle Stalin’s murderous havoc. His book “The Great Terror,” published in 1968, was among the 20th century’s most influential works of investigative history. Yet Conquest was also a seriously accomplished poet and a prolific letter-writer. His correspondence includes letters to Amis and Larkin (880 pages to the latter alone), as well as to the novelist Anthony Powell and poets including D.J. Enright, Thom Gunn, Vernon Scannell, Wendy Cope and others …

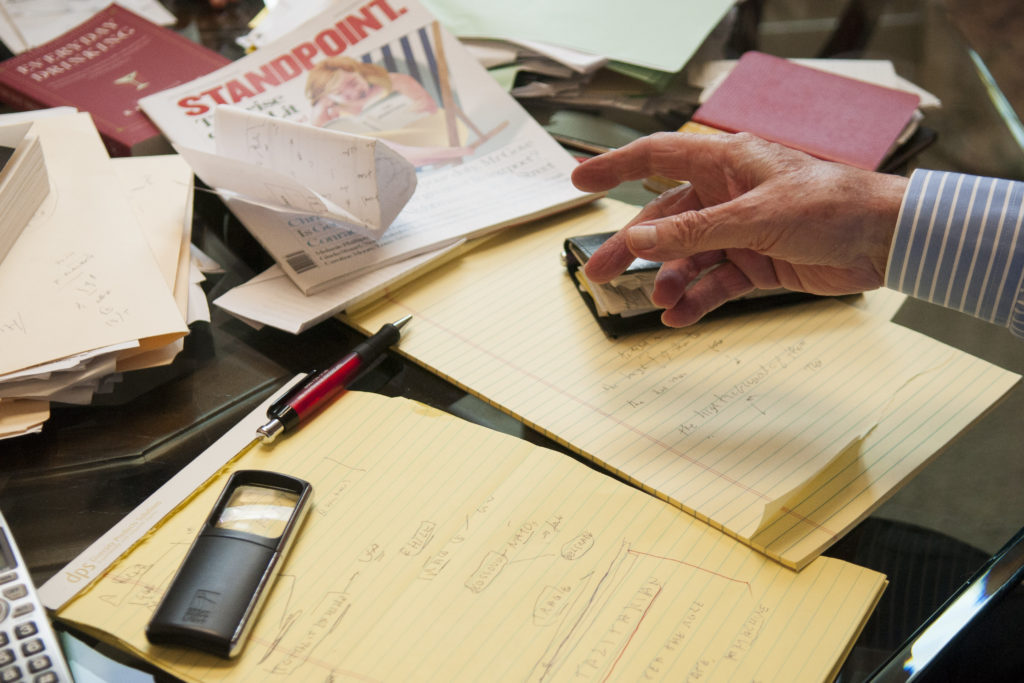

Banker boxes full of papers cover practically every flat surface in the Conquest household. Sideboards, tables, floors and shelves—all heave with typed and scribbled sheaves. Not only is Mrs. Conquest readying “The Great Terror” for its 50th anniversary edition this fall, she’s editing his complete poems—more than 400, some never published—for publication next spring. She’s also editing his memoirs—he died with one chapter unwritten—as well as a fat volume of his correspondence.

“There are thousands of pages of letters that he wrote,” Mrs. Conquest says. “Bob warmed up before a day’s work by writing letters. He would sit at his typewriter and he’d fire off.” Toward the end of his life, he would dictate email messages to Mrs. Conquest, who sent them from their shared account. “He was never really fond of trying to figure out the computer.”

The lot of a literary widow, Mrs. Conquest says, “is not a happy one, for she must master the management of her husband’s literary estate.” But she doesn’t sound grumpy when explaining that she has a veto over the use of his writings, including the power to say yea or nay to any requests to reprint them. This is all “notoriously tricky territory,” Mrs. Conquest concedes, and such widows have “long been caricatured in writerly circles as pantomime villains”—the younger wife who “single-mindedly devotes her remaining decades after her celebrated husband’s death to championing his artistic legacy and slaying those who dare to question it.”

One of the many comments the combox: “Mrs. Conquest seems to be an absolutely wonderful woman.” We couldn’t agree more. Read the whole thing here.

More papers: Conquest at work. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)