Remembering William Maxwell: “He used a pause better than most of us use a paragraph.”

Tuesday, October 30th, 2012In preparation for Stanford’s “Another Look,” a new book club launched by the English department at Stanford, I wrote a retrospective on author William Maxwell, whose masterpiece, So Long, See You Tomorrow, will be the inaugural book for “Another Look” on Monday, November 12. The book will be discussed by award-winning author Tobias Wolff, with Bay Area novelist, journalist, and editor Vendela Vida and Stanford’s lit scholar Vaughn Rasberry, to be followed by an audience discussion. More on “Another Look” here.

***

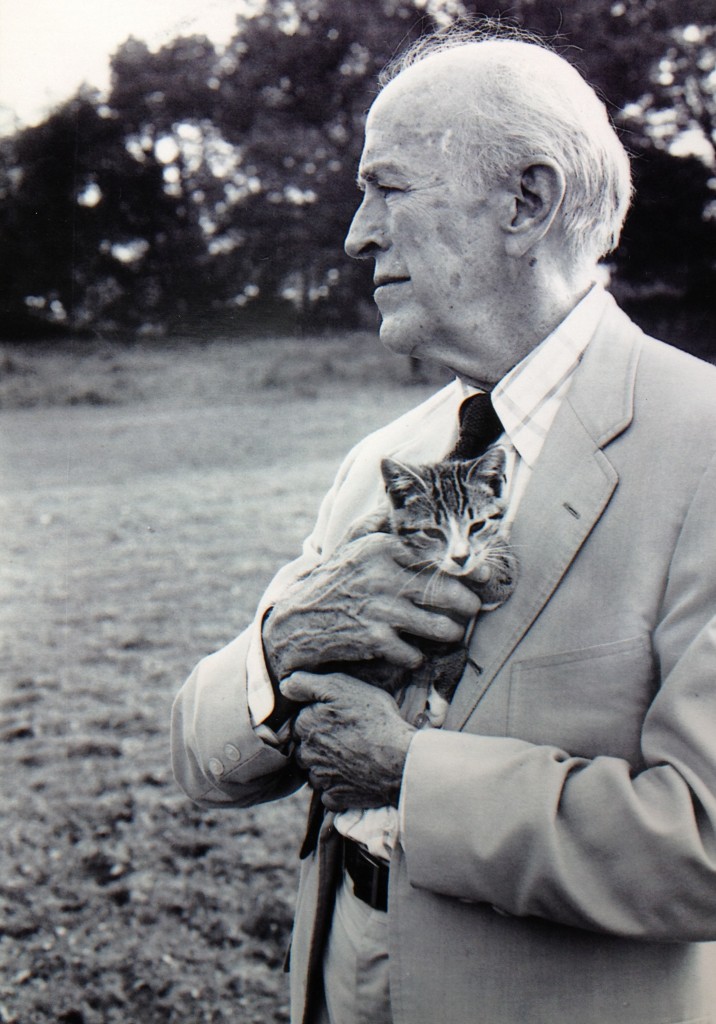

“I never felt sophisticated,” the erudite and elderly Midwesterner explained to NPR’s Terry Gross in 1995. His modesty is certainly one reason why William Maxwell remains a connoisseur’s writer, never achieving the wider recognition he deserves.

Yet Maxwell’s career was situated at the epicenter of American literature and letters: On staff at the New Yorker from 1936 to 1975, he was the editor of J.D. Salinger, Vladimir Nabokov, Eudora Welty, Frank O’Connor, John Cheever, and many other luminaries. He also contributed regularly to the magazine’s reviews and columns, and continued to do so until 1999, a year before his death. Maxwell wrote six novels, many short stories, a memoir, two books for children, and about forty short, whimsical pieces, which he called “improvisations.” Three volumes of letters have also been published.

Others have readily compensated for Maxwell’s modesty. Christopher Carduff, editor of the Library of America edition of the author’s complete works, once called him “a kind, wise, quiet voice. One of the essential American voices of our time.”

“I don’t think he tried very hard to promote himself,” said writer Benjamin Cheever, son of novelist John Cheever, in a telephone interview. “He was very, very quiet – both as a public person and as a conversationalist. He used a pause better than most of us use a paragraph.”

“He lived for art, its appreciation as well as its creation,” wrote John Updike in The New Yorker. “His shapely, lively, gently rigorous memoirs, out of the abundance of heartfelt writing he bestowed on posterity, are most like being with Bill in life, at lunch in midtown or at home in the East Eighties, as he intently listened, and listened, and then said, in his soft dry voice, exactly the right thing.”

The path of Maxwell’s life took few sharp turns. He was born in Lincoln, Illinois, on August 16, 1908. His professional life was almost entirely bound up with the New Yorker, where he worked for four decades – in a sense, he became the “company man” his father would have approved. After an intensely long and lonely bachelorhood, he married the most beautiful woman he had ever met. Their marriage lasted until her death, a week before his own. He and Emily (universally called “Emmy”) had two daughters – the first born when he was 46.

His work habits were relentlessly predictable: According to his daughter Katharine Maxwell, he was consistently in bed at 10 p.m., and up at 6 a.m. He didn’t like the superficial chitchat of cocktail parties. He excused himself abruptly from dinner parties at 9.45 p.m. – he wanted to be fresh to write the next morning.

About four-fifths of his oeuvre is set in or around his hometown. Thanks to him, Lincoln has become a landmark as indelible as Hannibal, Missouri, in the annals of American literature.

“The shine went out of everything”

There was one defining peak on the otherwise rather flat landscape of Maxwell’s life: his mother’s death in the 1918 influenza epidemic, when he was 10. He never really got over it; almost all his friends and acquaintances speak about it when recalling him. “He couldn’t speak of her without tears welling up in his eyes,” recalled his daughter, Katharine Maxwell. She said it resulted in a sort of flinty atheism, a grudge almost – “yet he said he thought God could write a better story than he could.” Maxwell’s friend and fellow writer at the New Yorker, Alec Wilkinson, described him as “melancholy-minded.” Said Wilkinson: “His mother’s death stamped him forever with an awareness of the fragility of human happiness. It kept him away from any religions. I remember him saying that ‘no one can fail to be astonished by creation – that’s as far as I’m going to go as to a governing faculty to the universe.’”