An American flâneur, and the world in a garage

Saturday, June 10th, 2023

Artist/painter J. Elliot (his Twitter handle is @j_elliot_art) is an East Coast artist working primarily in oil, as well as charcoal, watercolor, and pastels.

But he’s also one of a dying breed. A flâneur. Charles Baudelaire established the flâneur as a literary figure, referring to him as the “gentleman stroller of city streets.”

The thought started a sort of conversation on Twitter. Littérateur and pianist Koczalski’s ghost responded: “It isn’t possible to be a flâneur in America, for all of the obvious reasons.” Elliot, however, gave the concept an American spin: In the New World vernacular, flâneuring is “driving aimlessly around looking at yard sales and stuff.”

Is the day of the flâneur a thing of the past? In a 2013 article, “In Praise of the Flâneur,” in The Paris Review, Bijan Stephen writes: “The figure of the flâneur—the stroller, the passionate wanderer emblematic of nineteenth-century French literary culture—has always been essentially timeless; he removes himself from the world while he stands astride its heart. When Walter Benjamin brought Baudelaire’s conception of the flâneur into the academy, he marked the idea as an essential part of our ideas of modernism and urbanism. For Benjamin, in his critical examinations of Baudelaire’s work, the flâneur heralded an incisive analysis of modernity, perhaps because of his connotations: ‘[the flâneur] was a figure of the modern artist-poet, a figure keenly aware of the bustle of modern life, an amateur detective and investigator of the city, but also a sign of the alienation of the city and of capitalism,’ as a 2004 article in the American Historical Review put it. Since Benjamin, the academic establishment has used the flâneur as a vehicle for the examination of the conditions of modernity—urban life, alienation, class tensions, and the like. …

He goes on to assert the continued role of flâneuring in our times: “Real life hasn’t changed, and twentieth-century France was no different. Though Baron Haussmann’s avenues made flânerie more difficult, and though the rise of street traffic may have endangered those brave flâneurs who walked their turtles, the flâneur’s raison d’etre—to participate fully through observation—has always remained the same. Now that we’re comfortably into the era of the postmodern, perhaps it’s time to take a brief stroll into the past, to sample its sights and its sounds.”

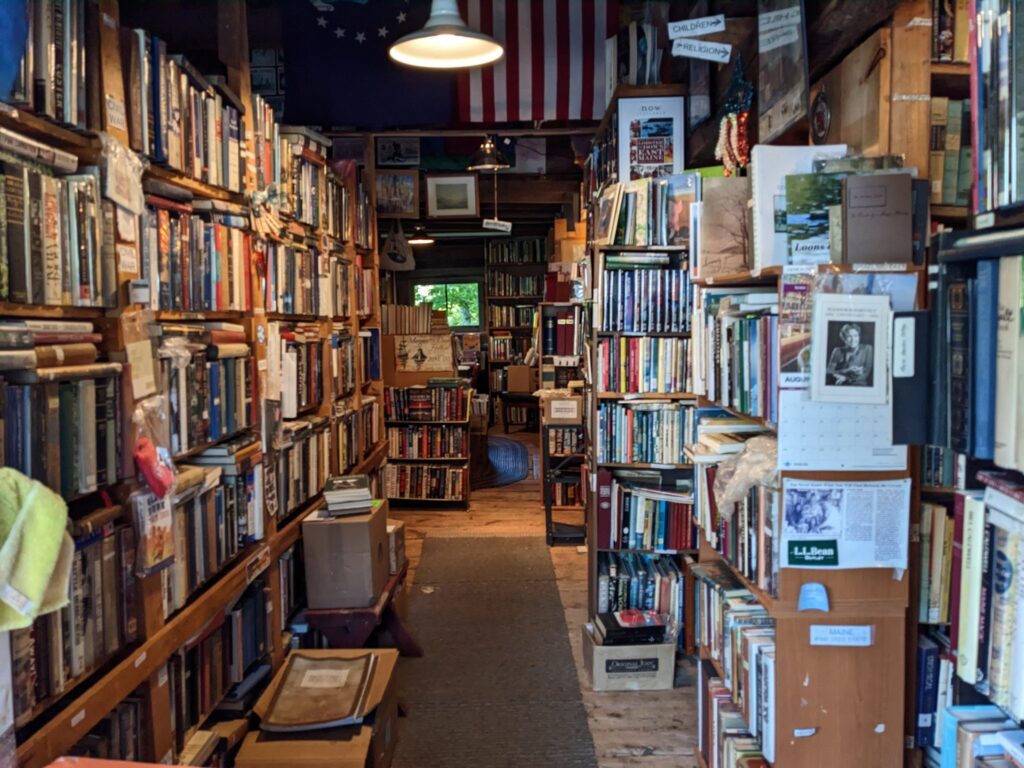

Elliot took the photos below during his flâneuring excursion in Machias, Maine, where he discovered “Jim’s Books,” located in Jim’s very own garage. Elliot tweeted this a day or two ago from his East Coast digs: “Today’s flâneuring: this bookshop a guy keeps in his garage.”

Elliot’s Twitter bio includes this: “Józef Czapski frequently advised me: when you’re having a bad day, paint a still life.” For some of us, maybe. Did he actually know the legendary painter, writer, diplomat? Tell us more… (I wrote about Czapski for the Wall Street Journal. Article here.