I’d say it’s more like a pear

A couple weeks ago, we wrote about Marilyn Yalom‘s latest book, The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love. Her onstage conversation at Kepler’s Books considered the history of the ❤, but left us a bit fuzzy about how the symmetrical shape took hold, sometime in the fifteenth century.

Her article in the Wall Street Journal this weekend gives the details: “the lack of real knowledge of physiology left open fanciful possibilities. The second-century Greek physician Galen asserted that the heart was shaped like a pinecone and worked with the liver. This view carried into the Middle Ages, when the heart first found its visual form as the symbol of love.”

Hence, “The earliest illustrations of the amorous heart, created around 1250 in a French allegory called ‘The Romance of the Pear,’ pictured a heart that looks like a pinecone, eggplant or pear, with its narrow end pointed upward and its wider, lower part held in a human hand.”

And then there’s Giotto, in his 1305 fresco of Caritas in the Scrovegni Chapel of Padua – (Proust makes much of this image – read about it here). I rather like the discreet pear-like objet passed between the lady and the saint (is she giving or taking it?) – a casual transaction like handing over a five-buck bill, that occurs cleanly without a fuss, rather than the messy, bloody, pulsating thing that makes a mess of our real lives.

But soon enough, science and biology took over, and that’s no fun at all:

The great exception, in this as in other matters of art and science, was Leonardo da Vinci, who studied both human and animal dissections. The painstaking illustrations in his notebooks show his longstanding dedication to anatomical accuracy. (Human dissection, long taboo, began appearing as early as 1315 in Italy, but it could be banned at any time, according to the mood of the pope.)

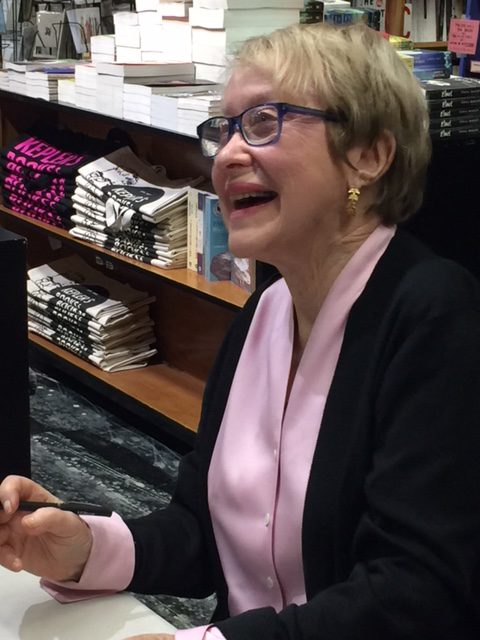

Queen of Hearts (Photo Margo Davis)

Andreas Vesalius, the 16th-century Flemish physician who is considered the father of modern anatomy, was allowed to dissect cadavers at the University of Padua, thanks to a judge who supplied him with the bodies of executed criminals. In his groundbreaking book “The Fabric of the Human Body” (“De humani corporis fabrica”), Vesalius corrected certain errors made by Galen that had been blindly repeated by successive generations of doctors since the second century.

The detailed plates in Vesalius’s “Fabrica,” like the drawings in da Vinci’s notebooks, pictured a heart that looked more like the real thing. Yet the advance of science did nothing to shake popular attachment to the image of the heart as bi-lobed at the top and pointed at the bottom.

Lub-dub, lub-dub, lub-dub. Here’s to artifice over the real thing, which brings us back to the pristine object we began with: ❤

Read the Wall Street Journal article here.

Tags: "Marilyn Yalom, Giotto, Leonardo da Vinci