“No poet in English writes with more authority”: Requiescat in Pace, Stanford poet Helen Pinkerton (1927-2017)

December 30th, 2017

At left, Helen Pinkerton at a Stanford event in 2010, with poet Turner Cassity at right. I’m in the center.

I met Helen Pinkerton fifteen years ago, when I wrote about her for Stanford Magazine. It was part of my effort to write about all the “Stanford poets” who had been in the orbit, however briefly, of poet-critic Yvor Winters – a circle that is largely unacknowledged and under-appreciated. Helen and I stayed in touch over the years, though not as frequently as either of us would have liked, for she was a indefatigable correspondent with a wide network and I had heavy writing commitments. (I have written about her here and here, among other places.)

En route to the Tucson airport yesterday, I received an email from her daughter Erica Light: “It is with infinite sadness I must let you know of the passing of the poet, scholar, Civil War historian, teacher, and friend to many, my mother Helen Pinkerton Trimpi, at her home in Grass Valley, California, at the age of 90. She made her peaceful transition yesterday, Thursday, December 28, 2017, in the morning with her family close about her.”

I would have written differently about Helen today, but there were nevertheless some good bits in my long-ago article:

“She has written some of the best poems of her generation,” says poet and scholar Timothy Steele, ’70. Pinkerton’s mentor, Yvor Winters, deemed her “a master of poetic style and of her material. No poet in English writes with more authority.” The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry, calling her style “austere,” notes that “her carefully crafted poetry is profoundly philosophical and religious.” …

“She has written some of the best poems of her generation,” says poet and scholar Timothy Steele, ’70. Pinkerton’s mentor, Yvor Winters, deemed her “a master of poetic style and of her material. No poet in English writes with more authority.” The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry, calling her style “austere,” notes that “her carefully crafted poetry is profoundly philosophical and religious.” …

Meeting Winters turned her aspirations upside-down. “I discovered a whole new world, which was the serious writing of poetry,” she says. She decided she’d rather be a mediocre poet than a first-rate journalist. For Pinkerton, poetry “was a better thing to do—it was more interesting and more valuable. It was a funny choice to make, I must say,” she adds wryly.

A second turning point occurred a few years later, when she read Moby Dick on an ocean liner going to Europe after completing her master’s. It became the subject of her 1987 scholarly work, Melville’s Confidence Man and American Politics in the 1850s—and of a number of her long narrative poems. “I gave a lot of my life to Melville,” she says.

But poetry always came first, she says. “For fifty years, Pinkerton has been writing beautifully crafted poems, but the age has favored flashier and more improvisational talents, and her work has not received the hearing it deserves,” Steele writes in the afterword to Taken in Faith. Flashy and improvisational she’s not—but with a little luck, she may outlast both those trends.

Over at the Weekly Standard, James Matthew Wilson, another of her many friends and correspondents, wrote a retrospective of her work in “It’s a Battlefield”:

Over seven decades, Helen Pinkerton has published a small number of poems admirable for their austere intellectual beauty, such as the newly collected “Metaphysical Song.”

First Principle

Being’s pure act,

Infinite cause

Of finite fact,

Essential being,

Beyond our sight,

Without which, nothing,

Neither love nor light

Like those of her mentor, Yvor Winters, Pinkerton’s lyrics exhibit both philosophical depth and clean, classical lines. She exceeds him in her careful definition of the human condition in terms of its inescapable orientation to the divine “First Principle.” …

Over the years, I have published several articles on Pinkerton, in hopes of bringing her metaphysical lyrics to a wider audience. I see now, however, that I have given short shrift to what may be her most lasting contribution to American letters, her five dramatic monologues in blank verse on the subject of the Civil War. These, I believe, will become classics: miniature epics that, like Virgil‘s Aeneid, draw public history and private tragedy into a poetic whole.

Over the years, I have published several articles on Pinkerton, in hopes of bringing her metaphysical lyrics to a wider audience. I see now, however, that I have given short shrift to what may be her most lasting contribution to American letters, her five dramatic monologues in blank verse on the subject of the Civil War. These, I believe, will become classics: miniature epics that, like Virgil‘s Aeneid, draw public history and private tragedy into a poetic whole.

And last but not least, Patrick Kurp of Anecdotal Evidence, wrote a tribute yesterday, “The Spirit’s Breath and Seed,” which includes a long excerpt from their own correspondence. (I believe I can take credit for introducing the two some years ago via email.) From Patrick:

Helen was among the last of Yvor Winters’ students to leave us. With their teacher, they – Helen, [Edgar] Bowers, Thom Gunn, Turner Cassity – along with J.V. Cunningham and Winters’ wife, Janet Lewis, represent the supreme flowering of the art of poetry in the United States. Helen’s interests always surprised me. She published a book on Melville and another, Crimson Confederates, devoted to the students at Harvard who fought for the Southern cause in the Civil War. Last year, Wiseblood Books published A Journey of the Mind: Collected Poems of Helen Pinkerton 1945-2016.

Only death stopped her. Helen’s collected poems, A Journey of the Mind, was published last year – a late harvest indeed, but that’s not all. Her final poem, “Dialogue,” appears in the Fall 2017 issue of Modern Age. And even her last few days held a surprise: two days before her death, she received the completed and bound copy of her interview from the Stanford Oral History folks, which, according to her daughter,”looks very nice indeed.” The link for the video interview is here.

Requiescat in pace, Helen. Your grace, intelligence, and fine poetic ear will be missed.

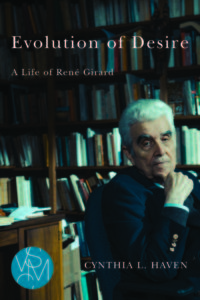

«Линчевание узнается по запаху», — сказал как-то Жирар, походя упомянув в разговоре роман Фолкнера. Эту непривычно жесткую фразу он произнес с несвойственным ему отвращением. Что имелось в виду, не уточнил, но друзья рассказали, что 1952—1953 годы, которые он провел на сегрегированном американском Юге, были для него сущей мукой. Кое-кто полагает, что именно там родилась его идея «козла отпущения», но это явная натяжка, к тому же недооценивающая его гениальную интуицию, которая сплетается со множеством наблюдений и научных находок в мощную теорию, описывающую положение человека и дающую ключ к нашему прошлому, настоящему и будущему. Эти идеи Жирар окончательно сформулировал уже после того, как книга «Обман, желание, роман» заявила о себе в литературном мире. «Я прожил год в Северной Каролине. — вспоминал он позднее. — Это было не худший штат на Юге, но полностью сегрегированный и довольно консервативный». Говорил об этом Жирар без сожаления: его завораживало буйство зелени, однако можно предположить, что роскошная краса этих мест только усиливала когнитивный диссонанс.

«Линчевание узнается по запаху», — сказал как-то Жирар, походя упомянув в разговоре роман Фолкнера. Эту непривычно жесткую фразу он произнес с несвойственным ему отвращением. Что имелось в виду, не уточнил, но друзья рассказали, что 1952—1953 годы, которые он провел на сегрегированном американском Юге, были для него сущей мукой. Кое-кто полагает, что именно там родилась его идея «козла отпущения», но это явная натяжка, к тому же недооценивающая его гениальную интуицию, которая сплетается со множеством наблюдений и научных находок в мощную теорию, описывающую положение человека и дающую ключ к нашему прошлому, настоящему и будущему. Эти идеи Жирар окончательно сформулировал уже после того, как книга «Обман, желание, роман» заявила о себе в литературном мире. «Я прожил год в Северной Каролине. — вспоминал он позднее. — Это было не худший штат на Юге, но полностью сегрегированный и довольно консервативный». Говорил об этом Жирар без сожаления: его завораживало буйство зелени, однако можно предположить, что роскошная краса этих мест только усиливала когнитивный диссонанс.

A belated postscript to

A belated postscript to