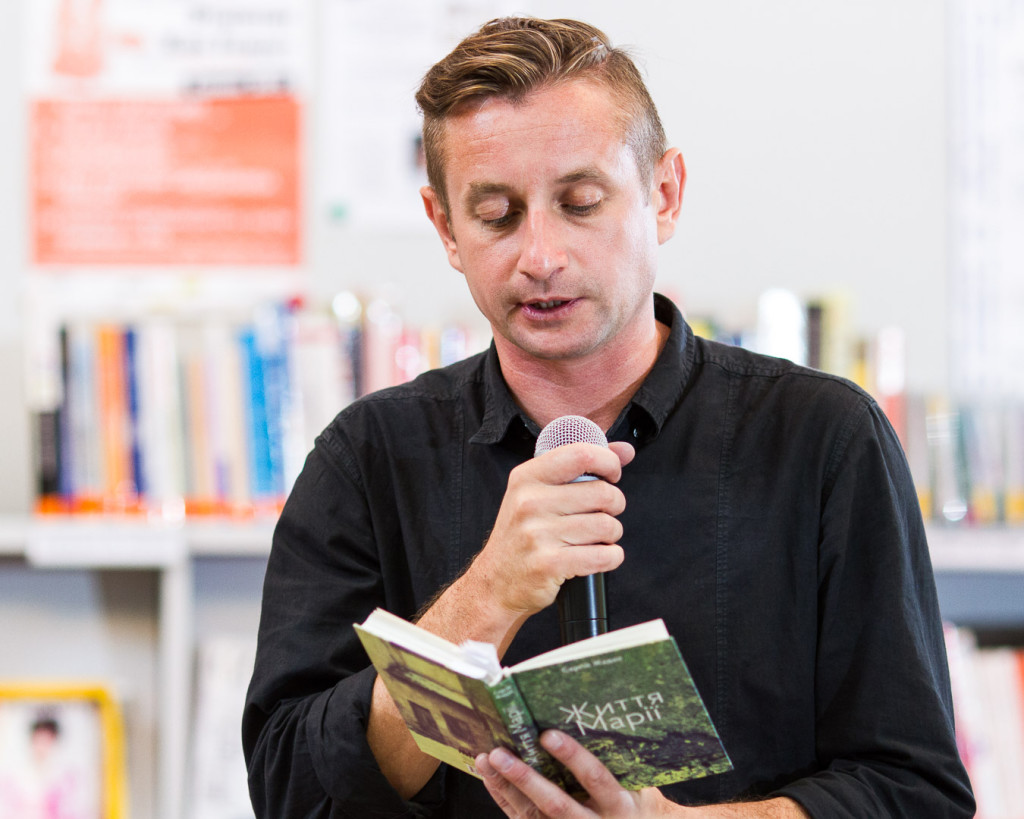

Ukrainian poet Serhiy Zhadan at the end of Europe

Friday, July 31st, 2015

Reading from “Lives of Maria” in Wrocław, earlier this year. (Photo: Rafał Komorowski)

We wrote about Serhiy Zhadan, Ukrainian poet, novelist, essayist, and translator over a year ago, in a post titled, “They told him to kneel and kiss the Russian flag. Then he told them to…” That’s when the pro-Russian demonstrators broke his skull with bats in his native Kharkiv, the second largest city of Ukraine, a place that has the misfortune to be close to the Russian border.

“Americans need to understand, in Eastern Europe, writers still have a huge influence on society,” Vitaly Chernetsky, a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Kansas told the New Yorker in a story here. “It may sound like an old-fashioned ‘poet stands up to tyranny’ story, like something out of Les Miz—‘Can you hear the people sing?’—but it’s really kind of like that. … He’s a writer who is a rock star, like Byron in the early nineteenth century was a rock star.”

We were happy to see him appear last week in a New York Review of Books blogpost by Timothy Snyder, “Edge of Europe, End of Europe.” Tim said “What Zhadan actually seems to aspire to – and here his willingness to risk his life for Europe is a clue – is what [writer Mykola] Khvylovy called ‘psychological Europe’: the acceptance of conventions, the work to transcend them, and the absolute indispensability of freedom and dignity for the effort.” The discussion includes Czesław Miłosz as well:

Zhadan’s most recent work, a collection of poetry published earlier this year entitled Lives of Maria, is a book of Ukraine’s war and of Zhadan’s own survival: “you see, I lived through it, I have two hearts/do something with both of them.” Yet as the book proceeds the meditations are increasingly religious, the poems often taking the form of conversations with Maria herself. No one, in eastern Slavic culture or anywhere else, combines the writerly personas of tough guy and holy fool as does Zhadan. He raps hymns.

Kindred spirit?

At points in Lives of Maria, Zhadan sounds like Czesław Miłosz, the twentieth-century Polish poet, who also strove toward Europe through both the local and the universal: “I wanted to give everything a name.” Miłosz was the preeminent poet of a borderland, one to the north of Kharkiv, Lithuanian-Belarusian-Polish (and Jewish) rather than Ukrainian-Russian (and Jewish). His position, not so different from Zhadan’s perhaps, was that Europe can best be recognized on the margins, that uncertainty and risk are more substantial than commonplaces and certainty. And indeed, the last section of Lives of Maria is devoted to Zhadan’s translations of Miłosz. Zhadan begins with two of Miłosz’s poems, “A Song on the End of the World” and a “A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto,” that ask the most direct questions about what Europeans did during the twentieth century and what they might and should do instead. The second poem communicates the pain and difficulty of actually seeing and trying to learn from the Holocaust, which was, or at least once was, a central idea of the European project. The first transmits, almost breezily, certainly eerily, what a European catastrophe might feel like. It concludes: “No one believes that it has already begun/Only a wizened old man who might have been a prophet/But is not a prophet, because he has other things to do/Looks up as he binds his tomatoes and says/There will be no other end of the world. There will be no other end of the world.”

Where Miłosz wrote in Polish that the old man had other things to do, Zhadan writes in Ukrainian that there were already so many prophets. Perhaps so. Pro-European Ukrainians are taking a chance, not demanding a future. They watch the Greek crisis too, and their position is often more scathing than anything western critics of the EU could muster. The point then is not certainty but possibility. Zhadan might well have died for an idea of Europe; other Ukrainians already have. Yet the risks he has taken, both physical and literary, are not in the service of any particular politics. Many of his essays and poems are about the attempt to understand people with whom he disagrees. He is an outspoken critic of his own government. Like Miłosz, who described Europe as “familial,” or like Khvylovy, who called Europe “psychological,” Zhadan is pursuing experimentation and enlightenment, a sense of “Europe” that demands engagement with the unmasterable past rather than the production and consumption of historical myth. “Freedom,” writes Zhadan in Lives of Maria, “consists in voluntarily returning to the concentration camp.”

It rather makes me hanker for a translation. Anyone? Oh well, you can read all of Tim’s article here.

I owe the Stanford University Libraries five books by Saturday, and naturally one of them is AWOL. The other four are stacked up neatly by the door, ready for return. Where did the fifth go? Meanwhile, in my search I stumbled across Dikran Karagueuzian‘s Conversations with

I owe the Stanford University Libraries five books by Saturday, and naturally one of them is AWOL. The other four are stacked up neatly by the door, ready for return. Where did the fifth go? Meanwhile, in my search I stumbled across Dikran Karagueuzian‘s Conversations with