Translation is the poor stepchild of literature – academics get more applause for producing their own books, not for translating the writing of others; for writers, it’s a distraction from their own work and not terribly well remunerated. Hence, a welter of books never appear on the international stage the way they deserve.

Translation is the poor stepchild of literature – academics get more applause for producing their own books, not for translating the writing of others; for writers, it’s a distraction from their own work and not terribly well remunerated. Hence, a welter of books never appear on the international stage the way they deserve.

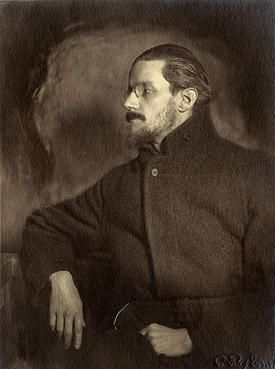

So it’s cheering to see a venture like the Paris-based Le Bruit du Temps, a publishing house crowded in one large room in one of the more picturesque neighborhoods in a city that has plenty of them. Founder and director Antoine Jaccottet has a desk in one corner; his collaborator, Cécile Meissonnier, has a desk on the other side. Pictures of Osip Mandelstam, Isaac Babel, and others are stuffed into the edges of a large mirror – they are the real masters here. The window next to it gives a clear view on a plaque indicates that James Joyce finished Ulysses across the street here, on rue du Cardinal Lemoine in the Latin Quarter.

Antoine Jaccottet, son of the poet and translator Philippe Jaccottet (who translated Goethe, Hölderlin, Mann, Mandelstam, Góngora, Leopardi, Musil, Rilke, Ungaretti, and Homer into French), worked for 15 years at the famous French publisher Gallimard, publishing classics, before he broke out on his own for a shoestring enterprise in 2008. The tight-budge endeavor, however, produces elegantly designed, finely crafted volumes.

Masterpieces don’t die, he says, but they can get lost in the noise of time. It’s the job of publishers to rediscover them for the public, and what better place than the small adventurous publishers who have a freedom and esprit not usually tapped by large publishing houses.

As I gaze over the offices teeming bookshelves, I notice an entire shelf of W.H. Auden in English. He’s one of the house’s authors. Le Mer et le Miroir … Auden in French? How does he come across? It’s difficult, Antoine admits, for the French to “get” Auden’s sensibility.

As I gaze over the offices teeming bookshelves, I notice an entire shelf of W.H. Auden in English. He’s one of the house’s authors. Le Mer et le Miroir … Auden in French? How does he come across? It’s difficult, Antoine admits, for the French to “get” Auden’s sensibility.

He’s also published Zbigniew Herbert in French, Lev Shestov‘s Athens and Jerusalem, the complete works of Isaac Babel, and Henry James‘s The Ambassadors. Even Shakespeare‘s (cough, cough) Henry VIII.

Mandelstam is, in a sense, the reason for the place. The title of the publishing house itself – “the noise of time” – is taken from the title of Mandelstam’s prose collection, which includes perhaps his most autobiographical writing. Antoine had been taken with the Russian poet in the 90s, and the translations and biography by the eminent scholar Clarence Brown. One of the first books the house published was Le Timbre égyptien (The Egyptian Stamp). The Ralph Dutli biography will be published this month. (The house published Dutli’s poems in 2009).

A piece of old France

Le Bruit du Temps’ books by and about Mandelstam illustrate an underlying principle at the house: Antoine publishes works that develop and deepen recurrent themes like a symphony. In 2009, he published published Browning’s L’Anneau et le Livre, republished G.K. Chesterton‘s out-of-print 1903 Robert Browning (Chesterton’s first book), Elizabeth Barrett Browning‘s Sonnets from the Portuguese and Henry James‘s Sur Robert Browning. That’s probably more Browning than Elizabeth Barrett ever saw.

Literary journalism, apparently, is as much in a crisis in France as it is here – the media often publishes book blurbs intact, and critics are famous for not reading the books they review. So how do people hear about books? Often, they don’t, he says.

As I leave, Antoine gives me a little souvenir of my visit, the publishing house’s brand new Le Bruit du Temps, a slim and elegant volume, fresh from the press. What could be more fitting?

He also shows me a rarely seen landmark as he shows me the door – at the back of the courtyard, between the buildings, in the soft sunlight of the late afternoon, the ancient Paris city walls of Philippe Auguste, the oldest surviving city walls, about the time of the poet Marie de France.

Postscript on 3/16: Nice mention on the University of Rochester’s “Three Percent” blog over here.

I owe the Stanford University Libraries five books by Saturday, and naturally one of them is AWOL. The other four are stacked up neatly by the door, ready for return. Where did the fifth go? Meanwhile, in my search I stumbled across Dikran Karagueuzian‘s Conversations with

I owe the Stanford University Libraries five books by Saturday, and naturally one of them is AWOL. The other four are stacked up neatly by the door, ready for return. Where did the fifth go? Meanwhile, in my search I stumbled across Dikran Karagueuzian‘s Conversations with