She picked up the pieces. Lili Brik and Mayakovsky in happier times, 1915.

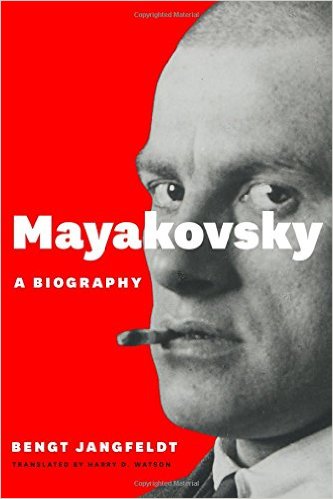

Bengt Jangfeldt wrote me a note to say he will be coming to town this autumn on Stanford-related business. We’re lucky to have him. The leading Swedish author, twice a winner of the August Prize and also a recipient of the Swedish Academy’s biography prize (and also a dear friend), is the author of biographies of Axel Munthe: The Road to San Michele (2003), Vladimir Mayakovsky: A Biography (2007), and also Язык есть Бог [Language is God], a biography of Joseph Brodsky (2010), and The Hero of Budapest: The Triumph and Tragedy of Raoul Wallenberg (2012). He is also the editor of Love is the Heart of Everything: Correspondence Between Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik 1915-1930. He is the Swedish translator the poetry of Mayakovsky (with Gunnar Harding), as well as the poetry and prose of Osip Mandelstam and Joseph Brodsky.

Master biographer

In anticipation of the visit from one of my favorite people, I wondered how his book on Mayakovsky, poet of the Russian Revolution, had fared since he gave me a copy in Stockholm last year. (I discussed his talk about it here.) To my surprise, I ran across “The Bad Boy of Russian Poetry” in the New York Review of Books, written by yet another friend, Michael Scammell:

When Vladimir Mayakovsky committed suicide on April 14, 1930, the news sent shock waves through the Soviet Union. Ilya Ehrenburg, who knew of Mayakovsky’s notorious gambling habit, thought he might have been playing Russian roulette with his beloved Mauser pistol and lost his bet. But Mayakovsky’s suicide note, written two days before his death, suggested otherwise. Asking his mother and sisters to forgive him and sardonically asking for there to be no gossip (“the deceased hated gossip”), Mayakovsky had appended a few lines from an unfinished poem:

The game, as they say,

Is over.

The love-boat has come to grief

On the reefs of convention.

Life and I are quits

And there’s no point

In nursing grievances.

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.

But that wasn’t the only mystery. In the tightly controlled Soviet Union, suicide was seen as a crime and an act of defiance, an assertion of personal freedom that contradicted the image of the state as a workers’ paradise. Why would someone as famous and popular as Mayakovsky have killed himself, even under provocation? What most of his readers didn’t know was that for the first time since the October Revolution, Mayakovsky was seriously disaffected. Stalin had started to purge his regime of “Trotskyists” and other perceived enemies, and two recent satirical plays of Mayakovsky, The Bedbug and The Bathhouse, had aroused official anger with their frank criticisms of government leaders and corrupt bureaucrats. His enemies whispered that he, too, was a secret Trotskyist and an elitist, out of touch with his proletarian base.

He was already being shadowed by the OGPU (the secret police), and its agents swarmed through his apartment the moment his death became known. They had long since penetrated Mayakovsky’s inner circle. Osip Brik had been an agent of the secret police in the early 1920s and he and Lili still maintained close contact with them; and the official death notice was signed by no fewer than three secret agents, in addition to a couple of Mayakovsky’s literary allies.

Michael Scammell and I had met, briefly and intermittently, during my years in London, where I volunteered my humble editorial services at the journal where he was editor and founder, Index on Censorship. He was already a bigshot and, as I recall, already working on his biography of Alexander Solzhenitsyn. We’ve corresponded in the years since.

He doesn’t stint on the passages about an important source for the Bengt’s book, the legendary Lili Brik herself:

Solzhenitsyn’s biographer

Jangfeldt introduces her in chapter two of his book, and she almost runs away with it, in part because she is such an arresting character herself. “I saw right away that Volodya was a poet of genius,” Jangdfeldt quotes her as saying in her unpublished autobiography,

but I didn’t like him. I didn’t like loud-mouthed people…. I didn’t like the fact that he was so big that people turned to look at him in the street, I didn’t like the fact that he listened to his own voice, I didn’t even like his name—Mayakovsky—so noisy and so like a pseudonym, vulgar one at that.

Nevertheless, it was almost a foregone conclusion that Lili would have an affair with the brawny young poet. When told about it, Brik allegedly said, “How could you refuse anything to that man!” But this was more serious than her earlier liaisons. Mayakovsky was an enormously persistent and demanding (and jealous) lover … Lili was happy to sleep with Mayakovsky, but held him at a certain length for nearly three years before suggesting he move in with herself and Osip, an arrangement that lasted on and off for the rest of his life. Meanwhile she lost no time in persuading her protégé to cut his hair and throw away his yellow blouse. She arranged for a dentist to make new teeth for him and bought him fancy new clothes to wear, so that he began to look more like an English dandy than the bohemian of old (though remaining just as wild in temperament).

I’ll likely be writing more about Lili Brik, one of Russia’s great literary widows – we have another mutual friend, Ellendea Proffer. The NYRB review concludes: “Jangfeldt devotes several chapters to his last agonizing months, tracking the events of his last fateful week day by day, until the poet concluded there was no other way to resolve both his emotional and his political dilemmas. Jangfeldt marshals the huge variety of sources he has amassed to create a gripping account of the poet’s tumultuous life and tragic death. … this book restores Mayakovsky to his rightful place in the pantheon of Russian letters and does him full justice.” Read the whole thing here.

A very cold August in Stockholm: Bengt, Humble Moi, Alexander Deriev, and Igor Pomerantsev (Photo: Liana Pomerantsev)

Tags: Bengt Jangfeldt, Lili Brik, Michael Scammell, Vladimir Mayakovsky