San Francisco Chronicle reviews “Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard.” We’re in the pink!

Saturday, June 30th, 2018

We’re in the pink! I biked down to the landmark Mac’s Smoke Shop on Emerson Street shortly after dawn this morning, to get my copy of the Sunday San Francisco Chronicle. And here it is: “A Life of the Mind,” a review of Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard by esteemed blogger, author, and critic Rhys Tranter. This is the first time René Girard’s work has appeared in The Chronicle since … oh, well, since I reviewed Battling to the End a decade ago. And there I am, on page 32 in the pink pages of the Chronicle‘s “Datebook” section, jostling for space right next to Bruce Lee (and, curiously, tucked away in a corner next to the review, Édouard Louis’s History of Violence). We’ll post a link when it’s up (POSTSCRIPT – link is here), meanwhile a few excerpts:

Cynthia L. Haven’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard is the first full-length biography of the acclaimed French thinker. Girard’s “mimetic theory” saw imitation at the heart of individual desire and motivation, accounting for the competition and violence that galvanize cultures and societies. “Girard claimed that mimetic desire is not only the way we love, it’s the reason we fight. Two hands that reach towards the same object will ultimately clench into fists.” … But it is the author’s closeness to the man once described as “the new Darwin of the human sciences” that brings this fascinating biography to life.

Cynthia L. Haven’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard is the first full-length biography of the acclaimed French thinker. Girard’s “mimetic theory” saw imitation at the heart of individual desire and motivation, accounting for the competition and violence that galvanize cultures and societies. “Girard claimed that mimetic desire is not only the way we love, it’s the reason we fight. Two hands that reach towards the same object will ultimately clench into fists.” … But it is the author’s closeness to the man once described as “the new Darwin of the human sciences” that brings this fascinating biography to life.

***

Haven was a friend of Girard’s until his death in 2015, and met with family members, friends and colleagues closest to him to prepare for the book. She recalls a calm and patient man who was generous with his time. “I came to his work through his kindness, generosity, and his personal friendship, not the other way around.”

He lived with his wife, Martha, on the Stanford University campus, and followed a strict working routine: “Certainly his schedule would have made him at home in one of the more austere orders of monks. His working hours were systematic and adamantly maintained.” He began his day at his desk at roughly 3:30 in the morning, broke for a walk and relaxation sometime around noon, and spent his afternoons either continuing what he had begun that day or meeting his responsibilities to students.

At home with Martha. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

One of the abiding questions that drives the book is how a man who appeared to lead such a quiet and ordered life was animated by some of the most troubling these in human history.

Adopting the lively and accessible style of an investigative reporter, Haven looks to Girard’s formative experiences for an answer. The reader is along for the ride as she drives a rented Citroën through southern France, or pores over archival images and family photographs. Her research is rich in important and surprising details, and there are entertaining tidbits of juicy academic gossip along the way.

In conclusion:

Evolution of Desire is the portrait of a provocative and engaging figure who was not afraid of pursuing his own line of inquiry. His legacy is not so much a grand theory as it is a flexible interpretive framework with useful social, cultural and historical applications. At a time when religious fundamentalism, violent extremism and societal division dominates the headlines, Haven’s book is a call to revisit and reclaim one of the 20th century’s most important thinkers.

Read about Evolution of Desire in the Wall Street Journal here. Or better yet, order a copy of the book itself here. Now in its second printing.

Postscript: the full link has been added here.

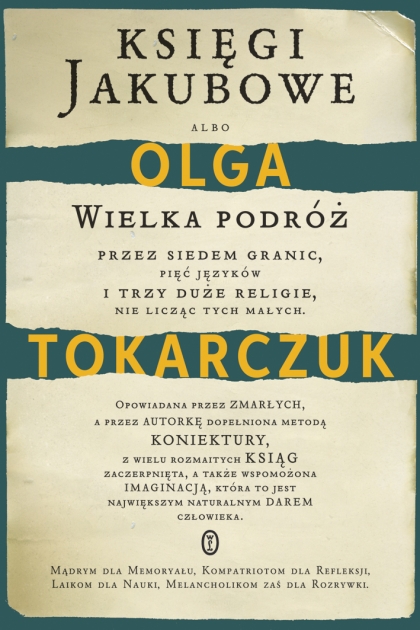

You’re also translating Tokarczuk’s magnum opus, the 900-page epic The Books of Jacob, which won the “Polish Booker” [That would be the Nike – ED.], and which is slated to be released in 2019. What can readers expect?

You’re also translating Tokarczuk’s magnum opus, the 900-page epic The Books of Jacob, which won the “Polish Booker” [That would be the Nike – ED.], and which is slated to be released in 2019. What can readers expect?