Tyler Cowen: “I’ve never been convinced that AI will rise up and destroy the world or turn us into paper clips.”

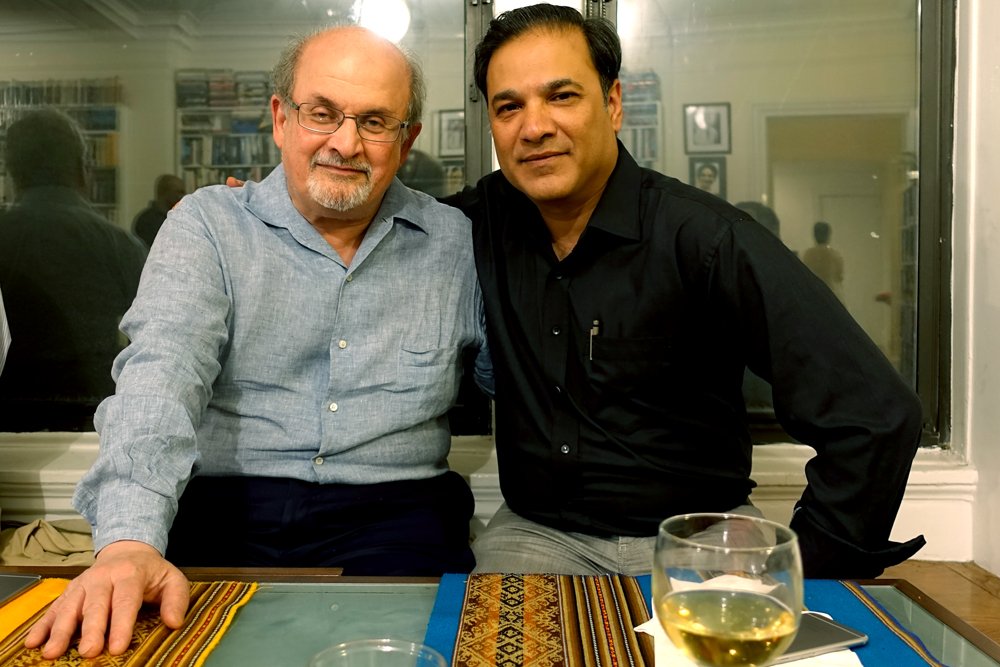

Sunday, February 26th, 2023Economist Tyler Cowen, is always quotable – even when he doesn’t try to be. For the three or four of you out there who haven’t heard of him, he’s professor of economics at George Mason University and the director of the Mercatus Center, a free-market research center and think tank. He is also the co-founder of the popular economics blog Marginal Revolution, and he’s host of the podcast series Conversations with Tyler – he interviewed my humble self some time ago here.

Check out this Q&A interview with Jon Baskin in “Progress Studies” in the current issue of The Point. The subject is artificial intelligence. When I saw the quote about paper clips, I knew this would have to be a Book Haven post. A couple excerpts that carry a lot of pith and punch:

JB: What kind of benefits do you see AI delivering? Will it bring us some of those big public benefits that you’ve talked about have been missing since 1973?

TC: I think within two years or so, AI will write about half of all computer code, and it will write the boring half. So programmers will be freed up to be more creative, or to try new areas where the grunt work is more or less done for them. That will be significant. Of course, the code has to be edited and checked, there will be errors. But it writes so much of it for you so quickly. And I think that will lead indirectly to some fantastic breakthroughs and creativity of programming.

And then, individuals will have individualized tutors in virtually every area of human knowledge. That is something that’s not thirty years off—I think it’s within one year, when GPT-4 is released, or when Anthropic is released. So imagine having this universal tutor. It’s not perfect, but much better than what you had before. We’ll see how these things are priced and financed. But that, to me, is a very significant breakthrough.

JB: Obviously, there’s a lot of anxiety among, I guess, humanities people, broadly speaking, but also people like the effective-altruism crowd thinking about the ways that AI could go terribly wrong. Do you think those worries have merit? How do we create a market and situation where we are able to advance the beneficial parts of AI and limit some of the potential damages?

TC: I’ve never been convinced by the scenario that the AI will rise up and destroy the world, or turn us into paper clips. [Read about how paper clips could bring about the end of the world here. – ED] I just don’t see the evidence. It doesn’t interact with the physical world in a way where it can do that. It doesn’t think. It’s a predictive language model.

You know, the humanities are going to have a lot of problems. So people are right to feel angst. But it’s also an opportunity. So far the most visible problem is students using GPT to write their term papers, right? I don’t know how we’ll deal with that. I don’t pretend to have the answer. I think there’ll be other problems related to misinformation, or maybe people treating it like a religious oracle. Every technological advance has difficulties, and this one will too.

***

JB: I want to talk a little bit about Tolstoy. Max Weber, in his famous 1917 lecture “Science as a Vocation,” says that Tolstoy is the person who most sharply raises the question of whether the advances of science and technology have any meaning that go beyond the purely practical and technical. And he quotes Tolstoy saying that, basically, for the person who puts progress at the center of their life, life can never be satisfying, because they’ll always die in the middle of progress. How would you respond to this charge from Tolstoy about progress?

TC: I’m pretty happy and Tolstoy was not, would be my gut-level response.

I would put it this way. If there was backwards time travel, and you had to send me back to his time, apart from satisfying some historical curiosity, I would be terrified at that prospect. Life in Tolstoy’s Russia was quite horrible. Even for the intelligentsia, never mind the peasants who had been recently freed from being serfs. And then that’s followed by Soviet Communism, as the reaction against how bad things were under the tsar. That’s awful. Give me Australia and Denmark and northern Virginia. Ask random immigrants or would-be immigrants: Would you rather migrate to Fairfax County or, you know, to Tolstoy’s Russia? It’s not even a choice. I don’t think you’d get many people going to Tolstoy’s Russia. And that, to me, suggests the importance of progress.

Read the whole thing here.