One wonders what Stanford Prof. John Freccero, one of the world’s leading Dante scholars, would have made of his own death, during the year the world is celebrating as the 700th anniversary of his Florentine master’s demise. No doubt he would have been honored and gratified. The author of the seminal Dante: The Poetics of Conversion had long since disappeared from the scene, quietly retreating within his home on Amherst Avenue. He died on Nov. 22.

“It seems natural that Freccero chose to devote his academic studies to Dante,” according to Johns Hopkins Magazine in 2008. “In one of his earliest memories, he’s a boy sitting on the lap of his Italian immigrant grandfather, staring at the frightening images accompanying The Inferno. ‘There is no Italian of my grandfather’s generation who didn’t know Dante,’ Freccero says. ‘That’s one of the things that’s so bizarre about him, that he is at once the most learned and the most popular of poets. Can you imagine a barber in Baltimore reciting Shakespeare? Of course you can’t. But you can’t imagine a barber in Italy not knowing Dante.'”

I interviewed him in the summer of 2012, and those encounters are cited in my book about his close friend and colleague, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard. (“I feel sometimes I am not worthy” of the friendship, he told me.)

Going back through those interviews this morning, I was surprised at their offhand depth and range, the casual erudition. (I’ve written about him before: Early sci-fi: how Dante warps time and space, and “By Love Possessed”? René Girard and John Freccero on Francesca da Rimini, among other places.)

I had studied with the Dantista some years before, in the late 1980s or early 1990s. As I wrote in Evolution of Desire:

“I met John Freccero at Stanford decades ago, when I attended his lectures on Dante—I remembered a potent concoction of urbanity, insight, and endless erudition. He assigned the multi-volume Charles Singleton prose translation of The Divine Comedy, urging us to buy the epic poem and commentary by Singleton as the definitive translation in English. Because of him, I still regularly refer to the thick gray volumes I found secondhand at Black Oak Books in Berkeley. “Why not a poetic translation?” a plaintive voice had queried from somewhere at the back of the large lecture hall. Freccero volleyed back with an appealing smile, “Because you should never give up on learning the Italian.”

“He disappeared from my life after the course was over, and returned when I realized that he had been a friend of Girard’s for nearly sixty years. He was a pivotal figure during Girard’s time at Johns Hopkins. Years later, Freccero helped bring Girard to Stanford. His observations were persuasive, and helped shape my understanding of the theorist I knew only in his last decade. Girard acknowledged the role of two Dantisti in his life during these years …”

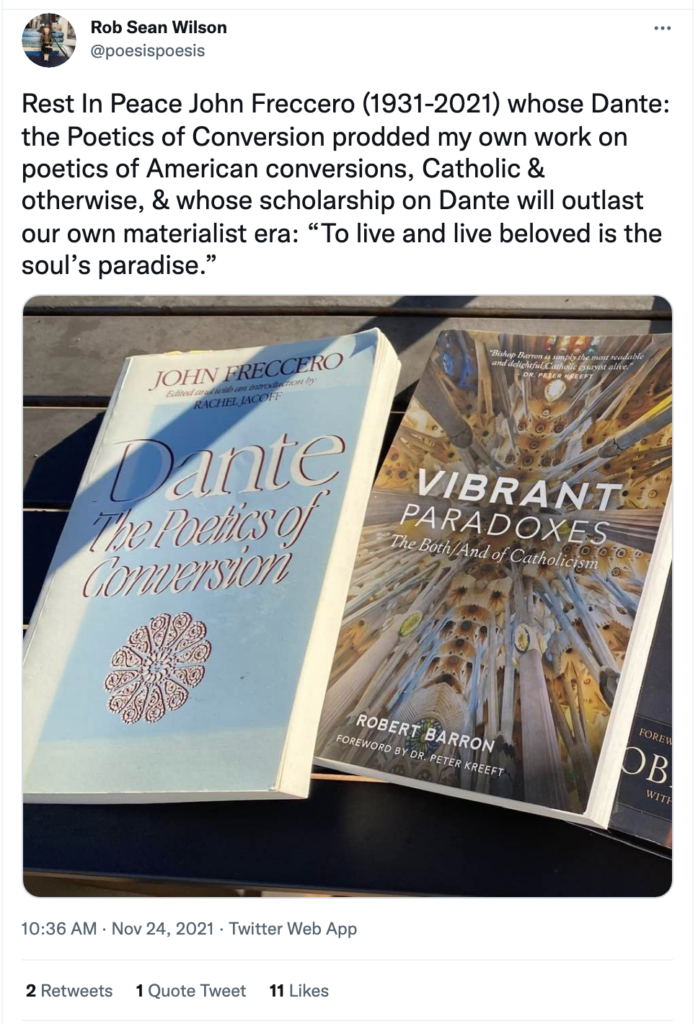

The outpouring since John Freccero’s death has been subdued – it occurred during Thanksgiving week, and the 90-year-old Dante scholar had long been in frail health. So far, the only comments I’ve seen have been on Twitter. (See below.)

In a life as intellectually radiant as his own, such a quiet death seems out of place – but perhaps one could say the same of Dante’s own malarial death, on returning from Venice, in 1321.

Let us quote another maestro, “Rest perturbèd spirit,” may angels guide thee… Dante described so many of them, after all.

Postscript on 12/3 from Stanford Prof. Grisha Freidin: Farewell, John. Your Dante course I sat through at Stanford in 1980 changed my life. For one, it was clear to me that one ought to be ashamed of teaching lit in a university without a serious study of Dante. I was fortunate to be able to audit his course at the outset of my career. It shaped my research, too, in many ineffable ways. John was also a good friend during his stint at Stanford that ended tragically when he lost his wife, a ballet dancer, to cancer. We lost touch after that, though I ran into him on occasion. Robert Harrison was his student, too, and held him in great esteem. Passing of a giant, who was part of the great tradition of Dante scholarship going back to Curtius and Auerbach.

Tags: Dante Alighieri, John Freccero, René Girard