Saint Augustine, pears, and “mimetic cascades”

November 8th, 2025

What did a fourth/fifth century saint from north Africa have to teach us about René Girard‘s mimetic theory? Philosophy professor Alexander Douglas of the University of St. Andrews has kindly allowed us to publish an excellent excerpt from his new and acclaimed book, Against Identity: The Wisdom of Escaping the Self, Penguin). Here it is:

“Three quarters of what I say is in Saint Augustine,” René Girard said in an interview some years ago.1 To understand Girard’s view of the human predicament, we can look at the Confessions of this early saint. One story that Augustine tells of his youth, with much contrition, is about how he and his friends stole some pears:

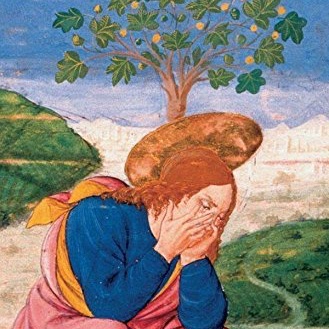

“Close to our vineyard there was a pear tree laden with fruit. This fruit was not enticing, either in appearance or in flavour. We nasty lads went there to shake down the fruit and carry it off at dead of night, after prolonging our games out of doors until that late hour according to our abominable custom. We took enormous quantities, not to feast on ourselves but perhaps to throw to the pigs; we did eat a few, but that was not our motive: we derived pleasure from the deed simply because it was forbidden.”2

At first it seems odd for Augustine to make so much of what seems like a minor teenage prank. But the imagery – the fruit that is enticing because it is forbidden – makes it clear that Augustine is using this episode as an allegory for the Fall of humanity.3

What Augustine wants to do with this story is probe into the mystery of our fallen condition. He is troubled by the fact that “there was no motive for my malice except malice”; his petty crime “lacked even the sham, shadowy beauty with which even vice allures us.”4 The object was not to eat the pears, nor to upset the owner of the vineyard, nor even entertainment – the theft was not challenging enough to constitute an exciting heist. It was simply to demonstrate his ability to act however he willed. Responding to no reasons, done to no conceivable purpose, this wanton act was meant to express his radical freedom. To conjure an action out of nothing, for no reason at all – what could be more radically free?

However, as Augustine looks back on the act, he realizes that it was not as original as he thought. In two ways, it was imitative, not original. First, his urge to express his own radical freedom was less a self-expression than an imitation of God’s omnipotence: a crippled sort of freedom, attempting a shady parody of omnipotence by getting away with something forbidden.”5 Secondly, he engaged in the act only because his friends did it too: “as I recall my state of mind at the time, I would not have done it alone; I most certainly would not have done it alone.”6 Augustine struggles to work out the reason for this. It is not simply that he did it for the sake of camaraderie. Nor was it only to share a joke. It was simply that “to do it alone would have aroused no desire whatever in me, nor would I have done it.”7

The theory of mimetic desire is very close to the surface of what Augustine writes here. His desire to act was prompted, or at least enhanced, by the apparent desire of his friends. Yet they were in the same position – only wanting to do it because the others did. This might look like a circular explanation, but in fact it shows how desire can emerge from nearly nothing, creating the illusion of the spontaneous will. We are prone to desire what others around us appear to desire, and this appearance can be a matter of a misread signal, a rumor, an accident mistaken for a ploy.8 Once an imitator has taken on a desire from the apparent desire of a model, however, she immediately becomes a model to others, and the mimetic cycle begins. Desire really does emerge where there was none before. It is never conceived by a radically free subject from nothing. Instead, it can emerge from a mimetic cascade, seeded by misperception.

Augustine’s story brings out two crucial aspects of Girard’s theory of identity. The first is that we readily believe ourselves to be little centres of omnipotence: freely deciding what to do, breaking rules, overcoming constraints and resisting impulses. The second is that the more we entertain this myth, the more profoundly we are in fact influenced by the examples of others. The radical egoist is an avid imitator in denial. This combination of prideful egoism and unconscious mimesis is the formula for the fallen condition in Augustine, and in Girard.

1 René Girard, When These Things Begin: Conversations with Michel Treguer, 133.

2 Augustine, Confessions, 1997, 2.9, 67-68.

3 Ibid., 68n32.

4 Ibid., 2.12, 70.

5 Ibid., 2.14, 71.

6 Ibid., 2.16, 72.

7 Ibid., 2.17, 73.

8 Jean-Pierre Dupuy, Le Sacrifice et l’envie – le libéralisme aux prises avec la justice sociale, 268.