Leading poetry critic Marjorie Perloff has died at 92: “Her passion was brilliant.”

March 25th, 2024Marjorie Perloff, one of America’s leading poetry critics, has died at 92. At Stanford, she was the Sadie Dernham Patek Professor of Humanities emerita. There will be many tributes in the days and weeks to come. Meanwhile, a few words of an early Facebook tribute from Stanford’s Hilton Obenzinger, who interviewed her for his “How I Write” program:

She lived a full life, fleeing Vienna as a child and ending up a leading critic. She always had an acute vision of current poetics, and she could be raucous and demanding and irritating and sometimes oddly narrow-minded, racially blinded on occasion, but she cultivated new experimental directions in poetry with a passion that was brilliant. I remember she sponsored a series of readings by avant-garde poets at Stanford. There were good turnouts – but with a remarkable absence of English Department faculty. She participated in a “How I Write” conversation. All I had to do was get her going and I didn’t have to say very much, she would just roll on in brilliant and funny bursts. Here’s an excerpt from the book that came from those conversations,. How We Write: The Varieties of Writing Experience:

Marjorie Perloff finds her subjects in a serendipitous or meandering fashion. She was asked to write an “omnibus review” of a hundred books of poetry, but she veered off when she discovered the work of one poet, Frank O’Hara, in an anthology. She was completely enthralled, and was compelled to write one of the earliest critical books about O’Hara’s work. “You’re going to write about something that speaks to you,” Perloff explained. “It does not mean it’s the greatest work; it just speaks to you. Nobody could be more different from me than Frank O’Hara, an Irish-American, gay, Catholic, male poet.” But she loved his work, his sense of humor; and she knew she liked the kinds of irony that O’Hara employs—so this became her project. Perloff explained that she has had to understand her own taste, “knowing what you like and don’t like,” and consequently her subject becomes a very personal choice, one that grows from that self-knowledge. “There are going to be certain things I never do like, that are, for me, sentimental,” and O’Hara was not one of those.

But it’s not only taste; it’s what she can offer to the conversation. Poets would often ask Marjorie Perloff why she hadn’t written about them or why she hadn’t written about some other writer. “It doesn’t mean you don’t like them,” she explained; but she may not have anything particular to say that hasn’t been said already. “There are a lot of people I like that I haven’t written about because I don’t feel I have anything to say that other people haven’t said. But that doesn’t mean that I don’t find them very interesting; it just means—Let’s take somebody like Faulkner, for instance. I adore Faulkner. But I don’t have anything to say about Faulkner, particularly.”

From Boris Dralyuk on Twitter: “I had this theory (ha…) that Marjorie was related to Shelley Winters. Like SW, she was a force, magnetic and grand. It was a joy to get her notes when she caught pieces of mine she liked, and it hurts to think that ’25 will arrive without one of her sumptuous New Year’s letters.“

From Derek Beaulieu on Twitter: “Rest in peace Marjorie Perloff (1931-2024); an incredible scholar, critic, and colleague … Marjorie passed away peacefully, surrounded by her family. She was herself to the end – funny, opinionated, generous, and fiercely devoted to her friends and family.“

Postscript from Peter Y. Paik of the University in Seoul, South Korea: “Ages ago when I was an undergrad interested in avant-garde poetry, it was Marjorie Perloff who made me want to pursue an academic career. I admired the clarity and grace with which she wrote on the most demanding sorts of texts, so much the inverse of much of the theory-heavy scholarship at the time. While my research interests moved in other directions, one of my fondest memories of graduate school was of getting to meet her in person at a conference in Cornell in 1995. She had an unabashed love for what she studied, which gave an invigorating and spirited quality to her conversation. Marjorie always retained the passion that drives one to study literature but which too often flags and flares out in the grind of the ivory tower. I pay my respects to a life well-lived, and offer the prayer that there will be more like her in the future.“

Postscript on March 29: There’s more. From Robert Pogue Harrison (read the whole piece here):

“At Stanford, Perloff had a profound and lasting impact on her students and colleagues. Robert Pogue Harrison, the Rosina Pierotti Professor of Italian Literature, Emeritus, team-taught Introduction to the Humanities and two graduate seminars on the French 19th century poets Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud with Perloff in the late 1990s. ‘No one who spent an hour in Marjorie’s company could ever forget her,’ said Harrison, professor of French and Italian. ‘In addition to being the best scholar of modern poetry of her generation, she was multi-lingual, immensely articulate, and a tour de force of wit and storytelling. She gave greatly more to Stanford than she took from it. Team-teaching with her was an exhilarating experience that I will always cherish.’”

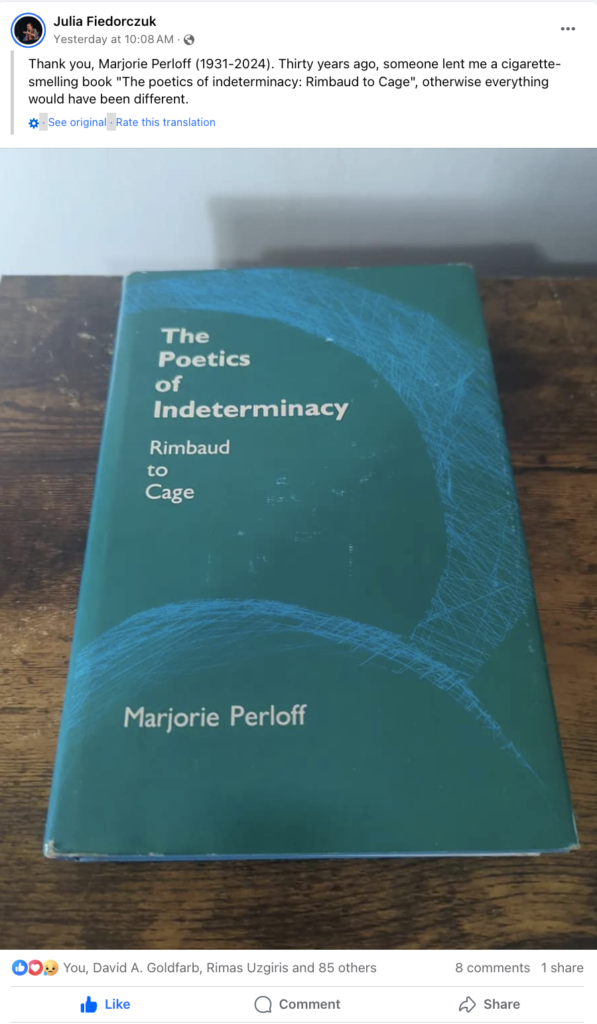

Postscript on March 26, from Polish poet Julia Fiedorczuk: