On being cool, or, “I Hope You Don’t Know That I Hope You Care That I Don’t Care What You Think About Me”

Friday, February 8th, 2019“Hot is momentary. It quickly turns to ashes. But cool stays cool,” said Robert Pogue Harrison, discussing Jim Morrison, the Doors, and the “ethos of cool” last year. He saw it as the triumph of Apollo over Dionysus.

Former Stanford fellow Chris Fleming has undertaken a study of “Theoretical Cool,” in the current Sydney Review of Books. As an associate professor of philosophy at the Western Sydney University, he had “a dawning realization that would take many years to coalesce: cool in the humanities isn’t that different from cool in other areas of cultural life, like planking, hotdog-legs photography, mason jar rehabilitation, and novels whose main character is a city.” It’s funny … and deadly serious, too, and surfaced in my Facebook feed. As he explained, “I wrote this, using only words.”

As for the photos below from his Facebook page, the author takes a shot at “cool” himself, in its various guises, some we might recognize.

In his words, then:

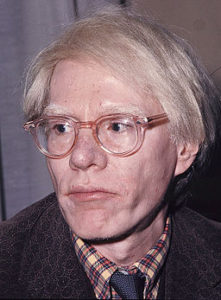

“The great Romantic injunction offered by the Aspiring Cool of Instagram to their potential audience is watch me not caring about whether or not you watch me (but please do watch me). The double imperative isn’t just a product of social media; the mating call of almost every VCP (Very Cool Person) – and every aspiring rebel – walking the street is: Look at me – I’m amazing! / Don’t you look at me – I don’t fucking care what you think! Which brings us necessarily to Andy Warhol, that erstwhile king of Union Square Weltschmerz, who gave us one of the clearest renderings of this double injunction. As far as I can recall, the only time Warhol ever looked like he had an elevated heartrate was when an interviewer suggested that he courted attention. In 1980 Warhol toured Miami Beach for his exhibition ‘Jews of the 20th Century’ at the Lowe Art Museum, when a reporter makes this statement:

Interviewer: Your work tends to be … I don’t want to use the word ‘sensational,’ because that connotes something bad, but you want attention…

Warhol: Oh no! No, that’s not true! I just work most of the time and … well, they make me do this … so …

The story of “Maurice Wu” demonstrates the perils and micromeasurements of cool. The lad arrived in Sydney via Hong Kong and was introduced to Fleming’s high school class. In the parochial school, “Brother Anianus put his arm around the new boy and announced to all of us: ‘This is Maurice Wu – and I bet he can breakdance better than any of you!'”

The story of “Maurice Wu” demonstrates the perils and micromeasurements of cool. The lad arrived in Sydney via Hong Kong and was introduced to Fleming’s high school class. In the parochial school, “Brother Anianus put his arm around the new boy and announced to all of us: ‘This is Maurice Wu – and I bet he can breakdance better than any of you!'”

“The problem was that breakdancing had been very popular at our school, like that groovy Saturday Night Fever dancing before it (or so my older brother swears, although one can never tell with him), but that time had passed and breakdancing was now something of a joke. Unaware, Brother Anianus pushed on: ‘Go on, Maurice, show them your moves!’ Maurice stepped to the side of the podium and proceeded to chainwave, robot, and donkey – all a capella – for about a minute. At the conclusion there was just the creak and whoosh of the fans above our heads – and then the whole year erupted in hysterical, ironic cheers, clapping, whooping, screaming ersatz approval. The year meeting ended. Unaware, Brother Anianus and Maurice Wu thought they’d done very well. It was, in fact, catastrophic (which is why I’ve used the pseudonym ‘Maurice Wu’).”

“Brother Anianus was really saying to us ‘Hey, listen up, funky town inhabitants – this guy is cool to the max.’ But it could only have the opposite effect – for a number of reasons. One is temporal. The historical miss here was very small; it had probably only been about one or two years since break dancing was at peak cool, at least at my Sydney suburban Catholic (ie. uncool) school. But something having-been-recently-cool is often not a mere approximation of being cool, only slightly less so. Despite the resurgence of vinyl, cool’s movement is often digital, not analogue. Although there are gradations of cool, at its peak, a near miss of cool is not like a near miss of a hole in golf or a near miss in a game of darts, where points decrease relative to the distance of the miss. No. In certain very delicate situations, trying to hit cool and missing it by a little is like hitting the wrong note on piano by a semi-tone: the smallest error will affect the biggest dissonance. (It didn’t help in this instance, of course, that the advocate here was a middle-aged man in a long white robe with a huge crucifix hanging from his neck – and whose name was pronounced, at least by us, as ‘any anus.’)”

Fleming describes “normcore” as “a cyborg word combining ‘normal’ and ‘hardcore.’” He continues, “Apart from being It, what exactly was normcore? To the outsider, normcore basically looks like what your uncle might wear to an engagement party at Sizzler: white Reeboks, a polo shirt, and Lowes sourced, bad-fitting jeans. Except, of course, it’s not like that at all; that’s just your uncle. Normcore only looks like that to, well, almost everyone. But ‘radical’ culture is often just like that.”

Fleming describes “normcore” as “a cyborg word combining ‘normal’ and ‘hardcore.’” He continues, “Apart from being It, what exactly was normcore? To the outsider, normcore basically looks like what your uncle might wear to an engagement party at Sizzler: white Reeboks, a polo shirt, and Lowes sourced, bad-fitting jeans. Except, of course, it’s not like that at all; that’s just your uncle. Normcore only looks like that to, well, almost everyone. But ‘radical’ culture is often just like that.”

As he explains, “a music video director wearing Hush Puppies and mum jeans in a Manhattan bar isn’t the same as … someone who isn’t a music video director wearing Hush Puppies and mum jeans in … a bar somewhere else. Again, normcore only looks like a loaned collection from Jerry Seinfeld’s wardrobe. To those in the know, it’s nothing of the sort. Just as an airport beagle can tell the difference between bowel cancer, a land mine, and MDMA residue at 100 metres, the truly cool can tell the difference between, say, K-Mart’s ‘Active’ running shoe line and Cristóbal Balenciaga’s Triple S trainers. (Apparently such a distinction exists, although it is lost on me.)”

He concludes: “Cool, of course, is one of taste’s dynamics, a silent, unavowable face of fashion. We can’t reliably predict its path because it never announces its itinerary. Its minimal requirement is simply to not be where it has just been; as such, the only rigorous science we can apply to it is hindsight. As Walter Benjamin reminded us many years ago, fashion more generally, articulates ‘the eternal recurrence of the new’. Cool is one antidote to the tendency for people’s taste to reify at a particular historical moment. We are familiar enough with the opposite: we see a person sitting on a train wrapped in a stonewash denim jacket, fluorescent parachute pants, and a hairspray-frozen bouffant which looks like a half-deflated basketball, and think quietly to ourselves ‘1983 was a pretty big year for you, huh?’ The idea is that at some point in our lives, for whatever reason, we became incredibly sensitive to the world around us; we might have had – to paraphrase lyrics from Dirty Dancing – the time of our lives – and as a result, we were dropped into a kind of temporal amber which preserved us like some insect from the Cretaceous period. 1983 passed but the uniform remained. This isn’t cool; the only amber the truly cool person is interested in is craft beer. They will not be frozen. (Of course, if the person on the train is 23, then all bets are off; along with the stonewash, this person is also sporting invisible inverted commas: they are quoting the 80s. To confuse this with the genuinely uncool is like believing, on the basis of her name and plethora of crucifixes, that Madonna was a nun.)”

Read the whole thing here.