She ought to know.

A week or so ago, we posted on Ellendea Proffer Teasley‘s terrific new memoir Brodsky Among Us (it’s here) which is a bestseller in Russia. One person, however, took exception to our criticism of Nobel poet Joseph Brodsky‘s translation of his own works from Russian into English. Her opinion is worth a read. Ann Kjellberg is the late poet’s literary executor and the editor of Brodsky’s Collected Poems in English. She is also the editor of the magazine Little Star. Here is what she had to say:

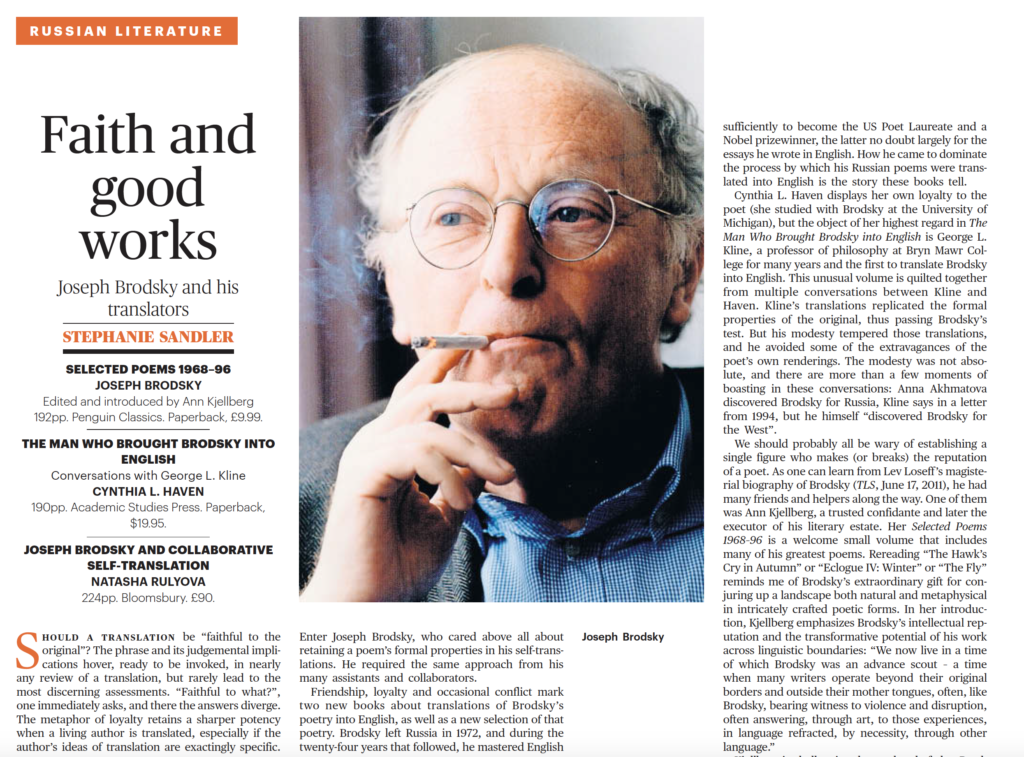

Poetry, having so little purchase in our reading life, deserves not to be approached on the defensive, but a few recent books that consider the work of Joseph Brodsky from a world perspective have once again raised the question of how effectively he has rendered himself for us in English, and it seemed like a good moment to look a little more deeply into the matter. Brodsky was born in 1940, in Leningrad, and came to the United States as an involuntary exile from the Soviet Union in 1972. By his death in 1996 he had translated many of his own poems into English, a language in which he had by then taught and written for nearly half his life. Coming from the hand of their author, these works fall somewhere between wholly subsidiary translation and original creation. Whether their language is poetically autonomous or too distortingly shaped by its Russian consanguinities has been debated since Brodsky first spoke up in the literary culture of his adoptive land.

To understand the terrain, a few words about Russian prosody are in order. The Russian language allows up to three unstressed syllables in a single word, in contrast to English, which normally follows an unstressed syllable with a stress. This fact allows Russian tremendous metrical versatility. Whereas English poetry is overwhelmingly iambic, Russian poetry spreads equally among many metrical forms, using many other combinations of stressed and unstressed syllables besides the iamb. Furthermore, as Russian is a highly inflected language, word order is permeable, and rhymes are very plentiful, allowing for a proliferation of complex musical schemes in its very young poetic tradition. Formal expression is very, very rich in Russian poetry and an integral part of the poetic experience. This flexibility has also allowed for a very full tradition of formal translation from other languages. Part of the reason Boris Pasternak’s translations of Shakespeare were said to rival the original is that Pasternak had such a plenitude of means at his disposal. The fact that many great literary practitioners (including Brodsky) were driven into translation as a safe literary occupation during Soviet times further enriched the translated canon in Russian, influencing Brodsky’s own perception of the possibilities of formal literary translation.

Brodsky, who received very little institutionalized education and came of age entirely outside the Soviet poetic establishment, was recognized early by his peers as a prodigy of poetic forms. It was his ear that singled him out among the swarm of young aspirants that formed around his mentor Anna Akhmatova, not his wit or his philosophical acumen. Many now regard him as the greatest innovator of Russian prosody since its forms were stabilized in the nineteenth century. He is particularly known for his expansion of the dol’nik, a looser form that cross-breeds accentual-syllabic verse with its wilder accentual cousin. For Brodsky, the musical dimension of a poem was inextricably wound into its semantic heart: the forms had coloration and value, as keys do for composers and tints for painters. He often spoke of the greyness or monotony of certain feet (the amphibrach, for instance) as an antidote to poetic grandstanding: such plays of self-effacement against assertion are very important in his work. Rhyming and metrical problem-solving are also essential to the wit of his poems, which again inflects poetic authority with impishness and deeply colors the poems’ tone. He used the pacing of poetic forms contrapuntally against the plotting and logic of his poems. The forms themselves—their shading, their pathos, their modulation of energy, their inherent proportionality—were absolutely inseparable for him from the poems and from his practice as a poet.

Brodsky, who received very little institutionalized education and came of age entirely outside the Soviet poetic establishment, was recognized early by his peers as a prodigy of poetic forms. It was his ear that singled him out among the swarm of young aspirants that formed around his mentor Anna Akhmatova, not his wit or his philosophical acumen. Many now regard him as the greatest innovator of Russian prosody since its forms were stabilized in the nineteenth century. He is particularly known for his expansion of the dol’nik, a looser form that cross-breeds accentual-syllabic verse with its wilder accentual cousin. For Brodsky, the musical dimension of a poem was inextricably wound into its semantic heart: the forms had coloration and value, as keys do for composers and tints for painters. He often spoke of the greyness or monotony of certain feet (the amphibrach, for instance) as an antidote to poetic grandstanding: such plays of self-effacement against assertion are very important in his work. Rhyming and metrical problem-solving are also essential to the wit of his poems, which again inflects poetic authority with impishness and deeply colors the poems’ tone. He used the pacing of poetic forms contrapuntally against the plotting and logic of his poems. The forms themselves—their shading, their pathos, their modulation of energy, their inherent proportionality—were absolutely inseparable for him from the poems and from his practice as a poet.

Furthermore, as he wrote powerfully in an essays on the translation of Osip Mandelstam (“Child of Civilization,” Less Than One), for a poet of Brodsky’s generation formal values carried a larger than musical meaning: they were a living link to the values of civilization for which poets toiled secretly in hidden rooms and basements, a whispered voice echoing from the past, an embedded conversation with their peers in books and abroad whose commitment to purely aesthetic values were ridiculed by the reigning Soviet orthodoxy. To perfect the musicality of one’s verse was to scorn the Soviet command that art hew to utilitarian ends; if a poem could be said to have a literal, exportable “meaning,” then that was precisely its least valued dimension.

Such was the import that the poetic forms carried for Brodsky and his fellow émigrés, like stowaways in their literary luggage.

By contrast, when Brodsky arrived in America in 1972, formal poetry was at a low ebb. Traditional forms were equated with loathed authority generally, the influence of the beats was pervasive and converging with continentally inflected, surrealist tendencies that would feed into the work of John Ashbery and the language poets, and the powerful generation that included Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath was moving toward a more personal, idiosyncratic line. Brodsky quickly took up the cause of form in poetry, both championing the practitioners he most admired and struggling, in his own verse, to render what he had already learned of its possibilities. Richard Wilbur wrote the new arrival a plaintive letter thanking him for his defense of Wilbur’s work and alluding to how demoralizing it was to write formal verse in such times. Brodsky’s heraldic defense of formal verse was at the time conflated with his predictably anti-Communist political views and seen as representing a general, disreputable conservatism.

This trend has reversed somewhat, or at least fragmented. We now have a more eclectic musical environment for poetry, for reasons perhaps similar to those reviving figurative painting and tonal musical composition and realist fiction. Yet Brodsky’s own influence is surely visible here. Brodsky, like W.H. Auden, harkened back to Thomas Hardy as a formative presence, and most contemporary poets would recognize a broad stream in our poetry extending from Hardy and Auden through Philip Larkin, Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, Brodsky, and Les Murray, to Paul Muldoon and Glyn Maxwell and Gjertrud Schnackenberg, for example. Many poets who do not write squarely in the formal tradition are more likely to visit it than they were in 1972.

His mentor.

Yet the legacy of that period of formal quiescence remains very much with us. Few American readers can read verse musically with any sophistication. The notion is still widespread that there is a binary division between “formal” and “free” verse—whereas much of the best of what is read as free verse is in fact deeply colored by forms (often shadows of iambic pentameter or echoes of the syllabic lines of Moore and Bishop), and there is a big difference, for example, between verse that follows a colloquial or spoken line and verse that treats language as a found object. Similarly, “formal” poetry is not just conservative poetry that adheres to old structures, but is an evolving medium that grows and develops and constantly makes new means available to the artist. The rhymes and meters of Muldoon alone should be sufficient to make the case that form can be modern.

Brodsky’s effort to enliven and expand the formal repertoire in English, which met with considerable resistance at the time, can surely now be judged a success. Yet critics continue to argue that the specific musicality of Brodsky’s English verse is too infected by “foreignness.” I think this suggestion deserves more scrutiny.

The English language is perhaps the most permeable on earth, and has been subject to external influences almost since its origins. Our own sacrosanct forms are borrowed from the French and Italian. Many of our greatest poets have struggled to infuse English poetry with the music of classical antiquity, for example. There is no reason why this process should stop now, or why our poetry might not continue to be renewed and refreshed through foreign engagements. The notion that to accuse a poet’s intonations of foreignness is sufficient to dismiss them seems unfounded, and unnecessarily to limit the potential resources available for the growth of our verse.

Let us return to the example of Brodsky. A master of an artistic medium comes to us from another language. He embraces our culture and our verse. He dedicates much of his short life to struggling mightily to rewrite his own work so that it can be read and understood by his compatriots. (This in contrast with Nabokov, an oft-mentioned comparison. Nabokov not only grew up speaking English in his aristocratic Saint Petersburg household; he abandoned composition in Russian to become an English-language writer. Brodsky remained primarily a Russian poet, crossing over into English and crossing back and embracing a bilingual literary career.) Should we reject this effort on the grounds of unfamiliarity alone? Or should we perhaps consider that Brodsky brings us important news that might enrich our tradition, which is currently suffering from an undeniable diminution of means? Should we consider whether the challenges that Brodsky’s English verse offer us may themselves be an indication of how our language and our receptivity have contracted? Might it be worth searching for the inner cadences and harmonies in what at first seems startling to us? Or asking ourselves how an apparent violation of convention might create a more muscular or versatile poetic medium?

A firm position on verse. (Photo: By Anefo / Croes, R.C.)

Here I speak mostly of Brodsky’s formal invention, because the case against his English verse is often tied to the case against formal translation generally. But readers should remember that Brodsky is a difficult poet in any language. Working with him on translations I frequently had occasion to see how he transformed a line that had been proffered by a translator not only with deeper music but deeper thinking—for him the two were intimately entailed. In a recent review in Tablet, Adam Kirsch remarks that some “unpoetic” literal translations of some of Brodsky’s work that appear as examples in a recent book sound “poetic” to him. But we cannot think that the “poetic” is a single category, a switch that can be turned on or off. There is a danger that we will accept translations that appeal to our notion of the “poetic,” or that satisfy our expectations of poetry, without questioning whether they even approach the author’s intellectual grist. Thus, like Alice, we go down a narrower and narrower literary hall.

In this vein, it’s worth considering the frequent case against Brodsky that his English is “unidiomatic.” We should reflect on the prejudices embedded in this judgment. When did being “idiomatic” become a decisive attribute for poetry? Our own language has a particular history of returning to its colloquial roots. From Chaucer, to Shakespeare, to Wordsworth, to Auden, our great poets have recalled us to the spoken line. But other traditions have developed differently. Many poetries have a high or courtly style and a colloquial style that poets draw into strategic conflict. Brodsky himself was often accused by Soviet critics of mixing high and low. Other poets have innovated by disrupting or vexing expectation, creating a new or idiosyncratic rhetoric. By keeping the spoken and the colloquial so central to our tradition, we may have deafened ourselves to the beauty and value of innovations like these.

Indeed, Brodsky used to complain that the criticisms leveled against him for his work in English were precisely the same as those leveled against him by his Russian detractors. One difference may be that challenging orthodoxies goes down more easily in literary circles when the orthodoxies are Soviet.

Ease of digestion is at a premium in our speed-reading culture. We seem more often than not to look for reasons not to address ourselves to challenging work. However, given that contemporary Americans are raised with so little education of the poetic ear, and that the number of students of Russian (and other languages) diminishes by the hour, we might hesitate before calling for the reprocessing of work by an acknowledged genius to suit our local tastes. Brodsky’s poems in English come to us double-refracted, as it were, through his own aesthetic character. They are spun once, in the original, and then spun again, just for us. We get his difficult message double-distilled. We inhabit his precise self-placement in one civilization, lifted up and dropped into a completely different one. It is a tall order. We can find reasons to avoid it. The routines of translation give us a chance to recast the problem into a Brodsky who goes down more easily. But that may not be the Brodsky we need.

(For a comprehensive study of Brodsky’s English and Russian prosody see Zakhar Ishov, Post-Horse of Civilisation [2008].)

Postscript on 5/15: Farrar, Straus & Giroux’s Work in Progress blog republished this post. Read it (again) here!

Brodsky, who received very little institutionalized education and came of age entirely outside the Soviet poetic establishment, was recognized early by his peers as a prodigy of poetic forms. It was his ear that singled him out among the swarm of young aspirants that formed around his mentor

Brodsky, who received very little institutionalized education and came of age entirely outside the Soviet poetic establishment, was recognized early by his peers as a prodigy of poetic forms. It was his ear that singled him out among the swarm of young aspirants that formed around his mentor