A hot fire on a cold night: Peter’s denial and “Mitsein”

Wednesday, September 27th, 2023

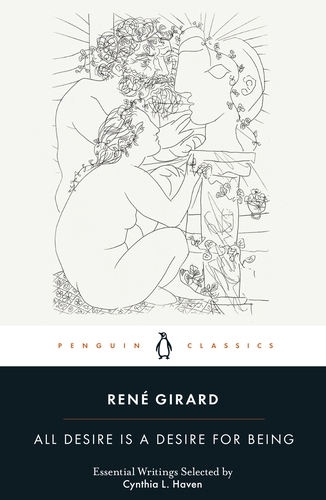

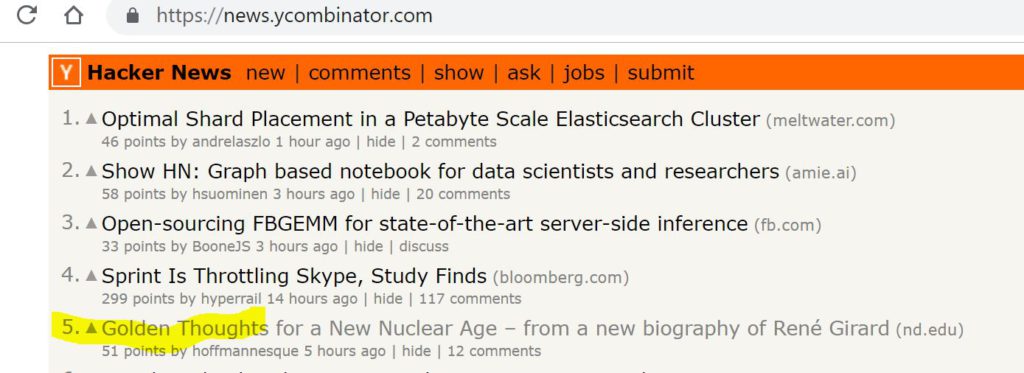

It’s hard to pick a favorite essay from my new anthology, All Desire Is a Desire for Being: Essential Writings – all of the pieces by French theorist René Girard are exceptional, otherwise I wouldn’t have picked them – but the essay on Peter’s Denial is certainly high on the list. So I was very pleased when the University of Notre Dame decided to publish the piece in its eminent Church-Life Journal, under the editor and friend Artur Sebastian Rosman, who is also a Czesław Miłosz scholar.

An excerpt from “The Question of Mimesis and Peter’s Denial“:

After Jesus had been arrested, the disciples fled in all directions, but Peter alone or, according to John, Peter and another disciple, followed at a distance right into the courtyard of the High Priest’s palace, and, I quote: “there he remained, sitting among the attendants, warming himself at a fire.” John says that “the servants and the police had made a charcoal fire, because it was cold, and were standing round it warming themselves.” And Peter too “was standing with them, sharing the warmth.”

The text shifts to inside the palace, where a hostile and brutal interrogation of Jesus was taking place. Then we shift back to Peter and, again I quote:

Meanwhile Peter was still in the courtyard downstairs. One of the High Priest’s servant girls came by and saw him there warming himself. She looked into his face and said, “You were there too, with this man from Nazareth, this Jesus.” But he denied it: “I do not know him,” he said. “I do not understand what you mean.” Then he went outside into the porch; and the girl saw him there again and began to say to the bystanders, “He is one of them,” and again he denied it.

Again, a little later, the bystanders said to Peter, “Surely you are one of them. You must be; you are Galilean.” At this he broke out in curses, and with an oath he said: “I do not know this man you speak of.” Then the cock crowed a second time; and Peter remembered how Jesus had said to him, “Before the cock crows twice you will disown me three times.” And he burst into tears.

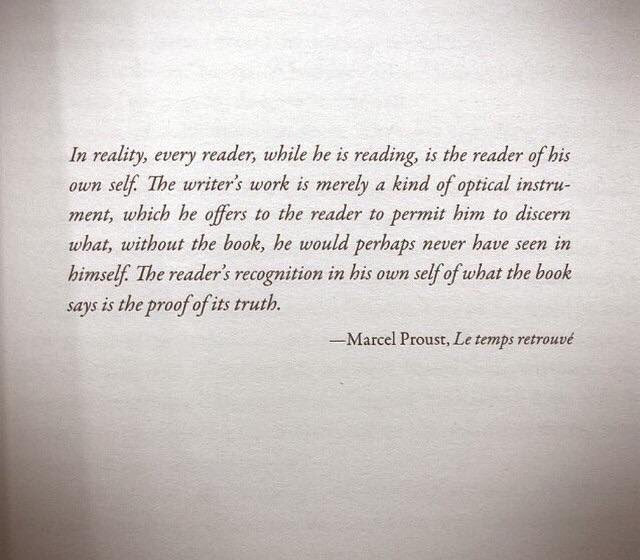

Auerbach makes some shrewd comments on that text: “I do not believe,” he writes, “that there is a single passage in an antique historian where direct discourse is employed in this fashion in a brief, direct dialogue.” He also observes that “the dramatic tension of the moment when the actors stand face to face has been given a salience and immediacy compared with which the dialogue of antique tragedy appears highly stylized.” It is quite true, and I am not averse to using such words as “mimesis” and “mimetic realism” to describe the feeling of true-to-life description which is created here, but I do not think that Auerbach really succeeds in justifying his use of the term “mimesis.”

Careful and sensitive as he is as a reader, Auerbach did not perceive something that is highly visible and which should immediately strike every observer: it is the role of mimesis in the text itself, the presence of mimesis as content. Imitation is not a separate theme but it permeates the relationship between all the characters; they all imitate each other. This mimetic dimension of behavior dominates both verbal and non-verbal behavior. Peter’s behavior is imitative from the beginning, before a single word is uttered by anyone.

In Mark and John, when Peter entered, the fire was already burning. People were “standing round warming themselves.” Peter too went to that fire; he followed the general example. This is natural enough on a cold night. Peter was cold, like everybody else, and there was nothing to do but to wait for something to happen. This is true enough, but the Gospels give us very little concrete background, very few visual details, and three out of four mention the fire in the courtyard as well as Peter’s presence next to it. They mention this not once but twice. The second mention occurs when the servant girl intervenes. She sees Peter warming himself by the fire with the other people. It is dark and she can recognize him because he has moved close to the fire and his face is lighted by it. But the fire is more than a dramatic prop. The servant seems eager to embarrass Peter, not because he entered the courtyard, but because of his presence close to that fire. In John it is the courtyard, upon the recommendation of another disciple acquainted with the High Priest.

A fire in the night is more than a source of heat and of light. A fire provides a center of attraction; people arrange themselves in a circle around it and they are no longer a mere crowd; they become a community. All the faces and hands are jointly turned toward the fire as in a prayer. An order appears which is a communal order. The identical postures and the identical gestures seem to evoke some kind of deity, some sacred being that would dwell in the fire and for which all hands seem to be reaching, all faces seem to be watching.

There is nothing specifically Christian, there is nothing specifically Jewish about that role of fire; it is more like primitive fire-worship, but nevertheless it is deeply rooted in our psyches; most human beings are sensitive to this and the servant girl must be; that is why she is scandalized to see Peter warm himself by that fire. The only people who really belong there are the people who gravitate to the High Priest and the Temple, those who belong to the inner core of the Jewish religious and national community. The servant maid probably knows little about Jesus except that he has been arrested and is suspected of something like high treason. To have one of his disciples around the fire is like having an unwelcome stranger at a family gathering.

The fire turns a chance encounter into a quasi-ritualistic affair and Peter violates the communal feeling of the group, or perhaps what Heidegger would call its Being-together, its Mitsein, which is an important modality of being. In English, togetherness would be a good word for this if the media had not given it a bad name, emptying it entirely of what it is supposed to designate.

This Mitsein is the servant girl’s own Mitsein. She rightfully belongs with these people; but when she gets there, she finds her place occupied by someone who does not belong. She acts like Heidegger’s “shepherd of being,” a role which may not be as meek as the expression suggests. It would be excessive in this case to compare the shepherd of being with the Nazi stormtrooper, but the servant maid reminds us a little of the platonic watchdog, or of the Parisian concierge. In John she is described as precisely that, the guardian of the door, the keeper of the gate.

This Mitsein is her Mitsein, and she wants to keep it to herself and to the people entitled to it. When she says: “You are one of them, you belong with Jesus,’ she really means, ‘You do not belong here, you are not one of us.”

We always hear that Peter acts impulsively, but this really means mimetically. He always moves too fast and too far; but still, why move so close to the center, why did the fire exert such an attraction on him?

Read the rest here.

My colleague and friend,

My colleague and friend,  I have appreciated Harrison’s analogy, though some of Girard’s other friends will no doubt rush to his defense, given Schliemann’s scandalous character—but Girard scandalized people, too: many academics grind their teeth at some of Girard’s more ex cathedra pronouncements (though surely a few other modern French thinkers were just as apodictic). He never received the recognition he merited on this side of the Atlantic, even though he is one of America’s very few immortels of the Académie Française.

I have appreciated Harrison’s analogy, though some of Girard’s other friends will no doubt rush to his defense, given Schliemann’s scandalous character—but Girard scandalized people, too: many academics grind their teeth at some of Girard’s more ex cathedra pronouncements (though surely a few other modern French thinkers were just as apodictic). He never received the recognition he merited on this side of the Atlantic, even though he is one of America’s very few immortels of the Académie Française.

From the jacket:

From the jacket: René Girard had reached the traditional midway point of life—35 years old—when he had a major course correction in his journey, rather like Dante. The event occurred as the young professor was finishing Deceit, Desire, and the Novel at Johns Hopkins University, the book that would establish his reputation as an innovative literary theorist. His first book was hardly the only attempt to study the nature of desire, but Girard was the first to insist that the desires we think of as autonomous and original, or that we think arise from a need in the world around us are borrowed from others; they are, in fact, “mimetic.” Dante’s “dark wood” is a state of spiritual confusion associated with the wild, dangerous forests. Three beasts block his path; the leopard, the lion, and the wolf represent disordered passions and desires. Dante’s conversion begins when he recognizes he cannot pass the beasts unharmed. Girard experienced his “dark wood” amidst his own study of the disordered desires that populate the modern novel. His conversion began as he traveled along the clattering old railway cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad, en route from Baltimore to Bryn Mawr for the class he taught every week. …

René Girard had reached the traditional midway point of life—35 years old—when he had a major course correction in his journey, rather like Dante. The event occurred as the young professor was finishing Deceit, Desire, and the Novel at Johns Hopkins University, the book that would establish his reputation as an innovative literary theorist. His first book was hardly the only attempt to study the nature of desire, but Girard was the first to insist that the desires we think of as autonomous and original, or that we think arise from a need in the world around us are borrowed from others; they are, in fact, “mimetic.” Dante’s “dark wood” is a state of spiritual confusion associated with the wild, dangerous forests. Three beasts block his path; the leopard, the lion, and the wolf represent disordered passions and desires. Dante’s conversion begins when he recognizes he cannot pass the beasts unharmed. Girard experienced his “dark wood” amidst his own study of the disordered desires that populate the modern novel. His conversion began as he traveled along the clattering old railway cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad, en route from Baltimore to Bryn Mawr for the class he taught every week. …