Teaching Tobias Wolff’s “Old School” to Hungarian teens – along with the reasons for rhyme

Thursday, April 16th, 2020Can Hungarian teenagers “get” an American novel set all the way back in the Kennedy Era? For a magical semester, author, educator, and translator Diana Seneschal taught her ninth-grade students at Szolnok’s Varga Katalin Gimnázium a novel by Stanford writer Tobias Wolff – in particular, 2003’s Old School. The upshot: they loved it. She had hauled copies all the way from the U.S. for her 33 students, paid for with an honorarium she had received in the U.S. At the beginning of the semester, Diana wrote me: “In addition, they have already read some Frost, we will read a Hemingway story or two, and I will tell them enough about Ayn Rand that they understand the change in the narrator’s response to her writing and attitudes.”

The reaction from her classes was enthusiastic: “One of the students asked her after the first class, ‘Is this book really for me to keep?'”

The reaction from her classes was enthusiastic: “One of the students asked her after the first class, ‘Is this book really for me to keep?'”

“When I told him it was, he said he was happy because he expected to reread it in the future. ‘I think this is my favorite book,’” he said.

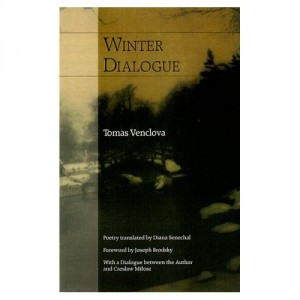

The Book Haven met Diana via her translations of the eminent Lithuanian poet (and our mutual friend), Tomas Venclova. So it’s fitting we republish this description of one of the classes, in which Wolff’s fictional students discuss poetry:

The third chapter of Tobias Wolff’s Old School, “Frost,” has the following exchange between the narrator and Purcell (p. 44):

Frost. I don’t even know why I bothered submitting anything, given how he writes. I mean, he’s still using rhyme.

Yeah, so?

Rhyme is bullshit. Rhyme says that everything works out in the end. All harmony and order. When I see a rhyme in a poem, I know I’m being lied to. Go ahead, laugh! It’s true–rhyme’s a completely bankrupt device. It’s just wishful thinking. Nostalgia.

The situation was this: At the beginning of the third chapter, we learn that George Kellogg, the excessively benevolent editor of the Troubadour, has won the first contest and will thus get to meet with Robert Frost. Purcell dismisses the whole enterprise.

First I asked the students to explain what Purcell was saying. They did it, point by point. Then I asked what they thought of it. In the first section, one student burst out, “That’s what I think.” A few others seemed to concur. They gave reasons: to rhyme, you have to invent something; rhyme sounds pretty, whereas the world often isn’t; rhyme imitates other rhymes and rhymers. Then I asked whether anyone saw or heard rhyme in a different way. Hands shot up. One student said that good rhyme is hard, so you can admire it. Another said that we are drawn to harmony. Another said that rhyme makes a poem memorable. Another suggested that Purcell was speaking out of jealousy. Then we started talking about how rhyme can draw associations between things.

The other section was more subdued but just as perceptive. Most of them rejected Purcell’s complaint from the start. One student pointed out that you can rhyme with the word “chaos,” in which case you aren’t creating harmony at all. Another said that we rhyme all the time, that rhyme is part of our everyday language. Others talked about how rhyme makes you think.

This set us up well for the next lesson, where we discussed the rest of the chapter. When I arrived, I saw students discussing the novel in the hallway.

At the start of the lesson, I played a muffled recording of Frost reading “Mending Wall,” which they had read with me. In the first section, no one seemed to know what was going on until the very end, when one student cried out in Hungarian, “Emlékszem!” (“I remember it!”). In the other section, they recognized it right away. We then talked about the passage in Old School where the headmaster introduces Frost, and the one where the narrator’s understanding of “Mending Wall” changes as he listens to Frost reading it aloud. (This is a fictional Frost, but I can imagine Frost reading like this.)

Then the teacher Mr. Ramsey’s challenge: Aren’t those poetic forms–rhyme, stanzas, etc.–outmoded? Shouldn’t poetry reflect modern consciousness? And Frost’s response (of which this quote, from p. 53, is just a fraction):

I am thinking of Achilles’ grief, he said. That famous, terrible, grief. Let me tell you boys something. Such grief can only be told in form. Form is everything. Without it you’ve got nothing but a stubbed-toe cry—sincere, maybe, for what that’s worth, but with no depth or carry. No echo. You may have a grievance but you do not have grief, and grievances are for petitions, not poetry.

You could read all the class lessons here. Or read her blog Take Away the Takeaway here. Or go to her TED talk here.