Elizabeth Bishop’s class at Harvard: “She wanted us to see poems, not ideas,” says Dana Gioia

Tuesday, December 1st, 2020

Harvard’s Kirkland House: they studied in the basement, among unwanted couches and broken bikes. (Photo: Wikipedia)

A university student should have at least one unforgettable teacher during his or her formative years. So it was with poet Dana Gioia. In 1975, he began his last year as a graduate student in English at Harvard. He faced a choice: taking Robert Lowell‘s class on 19th century poets, or a relatively unknown Elizabeth Bishop teaching “Studies in Modern Poetry.” She rarely attracted more than a dozen students – but she attracted this one, who would go on to be chairman of the NEA. The class dwindled down to five, four of them undergraduates by the second meeting. But the friendship of the poet and the poet-to-be endured. After each class, he walked with “Miss Bishop” to their respective quarters, since they lived in the same direction from Harvard’s Kirkland House.

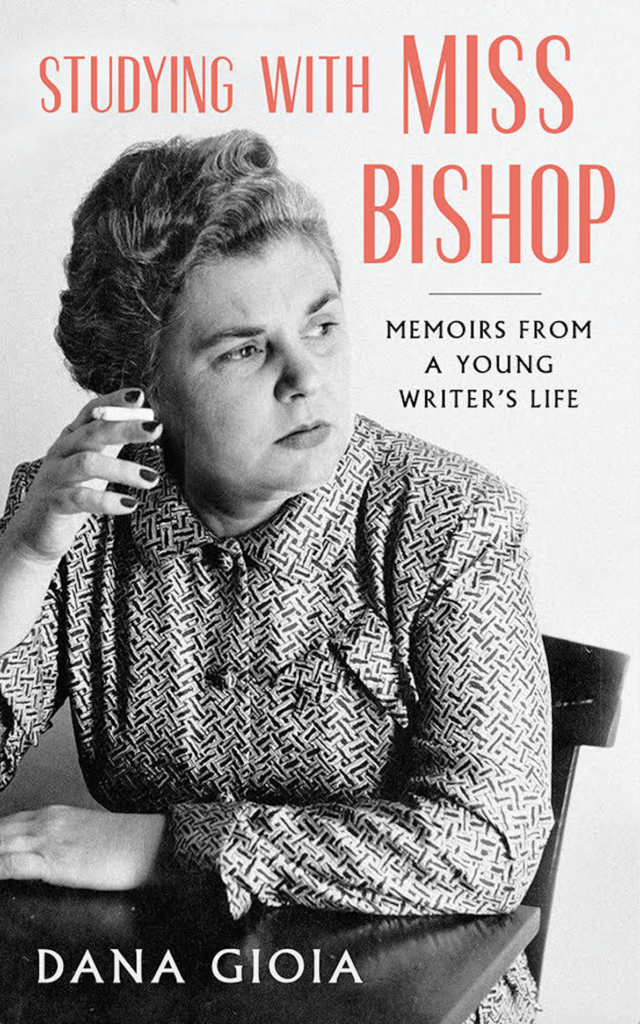

The story is one of several told in Dana Gioia’s new book Studying with Miss Bishop: Memoirs from a Young Writer’s Life, out in January with Paul Dry Books. Also included in the collection are accounts of John Cheever, Robert Fitzgerald, James Dickey, and more. The publisher, too, has a story: he was a stock options trader, and a successful one, but the Harvard grad had a secret yen to be a publisher (read that story here). The Stanford Publishing Course convinced him to have a go.

Back to the class in the basement of Kirkland House: Elizabeth Bishop was new to teaching and it showed. “I’m not a very good teacher,” she began. “So to make sure you learn something in this class I am going to ask each of you to memorize at least ten lines a week from one of the poets we are reading.”

“Memorize poems?” one of the dismayed students asked. “But why?” Miss Bishop’s reply was modest and sincere. “So that you’ll learn something in spite of me.”

“Memorize poems?” one of the dismayed students asked. “But why?” Miss Bishop’s reply was modest and sincere. “So that you’ll learn something in spite of me.”

The class final at the end of the term, in Dana’s own words: “Our final examination surprised even me. A take-home test, it ran a full typed page (covered with the hand-scrawled corrections that by now were her trademark) and posed us four tasks unlike any we had ever seen on a college English exam. Furthermore, we were given exact word lengths and citation requirements, as well as this admonition as a headline: ‘Use only your books of poems and a dictionary; please do not consult each other.'”

The final hurdle of the test was this, in Bishop’s words:

Now, please try your hand at 24 lines of original verse; three poems of eight lines each, in imitation of the three poets studied, in their styles and typical of them. (In the case of Lowell, the style of Lord Weary’s Castle.) I don’t expect these pastiches to be great poetry! – but try to imitate (or parody if you prefer) the characteristic subject-matter, meter, imagery, and rhyme (if appropriate).

We may not have consulted each other about the answers to this test, but, walking out of Kirkland after the last class with the final in our hands, we could not help talking about the questions. Miss Bishop had gone off to her office, and we were alone.

“I can’t believe it,” one of the undergraduates moaned. “We have to write poems.”

Someone else offered the consolation that at least everything else on the exam was easy.

“Yeah, but we still have to write poems.”

***

His conclusion: “By this time, I had realized that, for all her fumbling disorganization, Miss Bishop had devised – or perhaps merely improvised – a way of teaching poetry which was fundamentally different from the manner conventionally professed in American universities. She never articulated her philosophy in class, but she practiced it so consistently that it is easy – especially now, looking back – to see what she was doing. She wanted us to see poems, not ideas. Poetry was the particular way the world could be talked about only in verse, and here, as one of her fellow Canadians once said, the medium was the message. One did not interpret poetry; one experienced it. Showing us how to experience it clearly, intensely, and, above all, directly was the substance of her teaching. One did not need a sophisticated theory. One needed only intelligence, intuition, and a good dictionary. There was no subtext, only the text. A painter among Platonists, she preferred observation to analysis, and poems to poetry.”

In case you missed it, The New Yorker has a long feature by Claudia Roth Pierpont,

In case you missed it, The New Yorker has a long feature by Claudia Roth Pierpont,  A villanelle, for those of you who don’t know the lovely form with its remarkable incantatory power, is a 19-line poem with a rhyme-and-refrain scheme that runs as follows: A1bA2 abA1 abA2 abA1 abA2 abA1A2 where letters (“a” and “b”) indicate the two rhyme sounds, upper case indicates a refrain (“A”), and superscript numerals (1 and 2) indicate Refrain 1 and Refrain 2.

A villanelle, for those of you who don’t know the lovely form with its remarkable incantatory power, is a 19-line poem with a rhyme-and-refrain scheme that runs as follows: A1bA2 abA1 abA2 abA1 abA2 abA1A2 where letters (“a” and “b”) indicate the two rhyme sounds, upper case indicates a refrain (“A”), and superscript numerals (1 and 2) indicate Refrain 1 and Refrain 2. We’ve written about Berkeley poet

We’ve written about Berkeley poet CB: George Herbert,

CB: George Herbert,