TLS readers respond: Hölderlin’s Greece, and René Girard on pacifism

Saturday, October 6th, 2018 Watchful Book Haven readers alerted me to letters that have been published at the Times Literary Supplement, touching on subjects we have written about in the past. Two are in the September 28 letters column of the eminent weekly!

Watchful Book Haven readers alerted me to letters that have been published at the Times Literary Supplement, touching on subjects we have written about in the past. Two are in the September 28 letters column of the eminent weekly!

The first, forwarded to us by Elizabeth Conquest, concerns the recent TLS piece on my Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard. Read about it here.) Was René Girard a pacifist? It’s a subject I tackle in the postscript of my book:

The first, forwarded to us by Elizabeth Conquest, concerns the recent TLS piece on my Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard. Read about it here.) Was René Girard a pacifist? It’s a subject I tackle in the postscript of my book:

René Girard is not a pacifist. That was the word I received from Paul Caringella, a friend and longtime visiting fellow at Stanford, who had been the first reader for this book. He had sent me a quick note of correction to an early draft of this manuscript, which he thought might lead readers to that erroneous conclusion.

I had not put Girard in quite those terms, but once the issue came up, I realized I had made certain assumptions. Given Girard’s emphasis on the renunciation of violence and his warnings about the “escalation to extremes,” it stands to reason that he would advocate disarmament and pacifism. How could one sanction any participation in the calamity of war, the inevitable atrocities and injustices, the destruction of cities, the “collateral damage” as

civilians are pulled into the slaughter, the unstable and temporary peace that follows? “René doesn’t belong to any ‘ism.’ He’s not an ‘ism’ man,” Paul later explained. “People of his stature are not going to be put in classifications like that.”

David Martin of Woking, Surrey, takes on the question with his own example of the complicated relationship between pacifism and violence. Many thanks, once again, to Liddie for the heads-up.

***

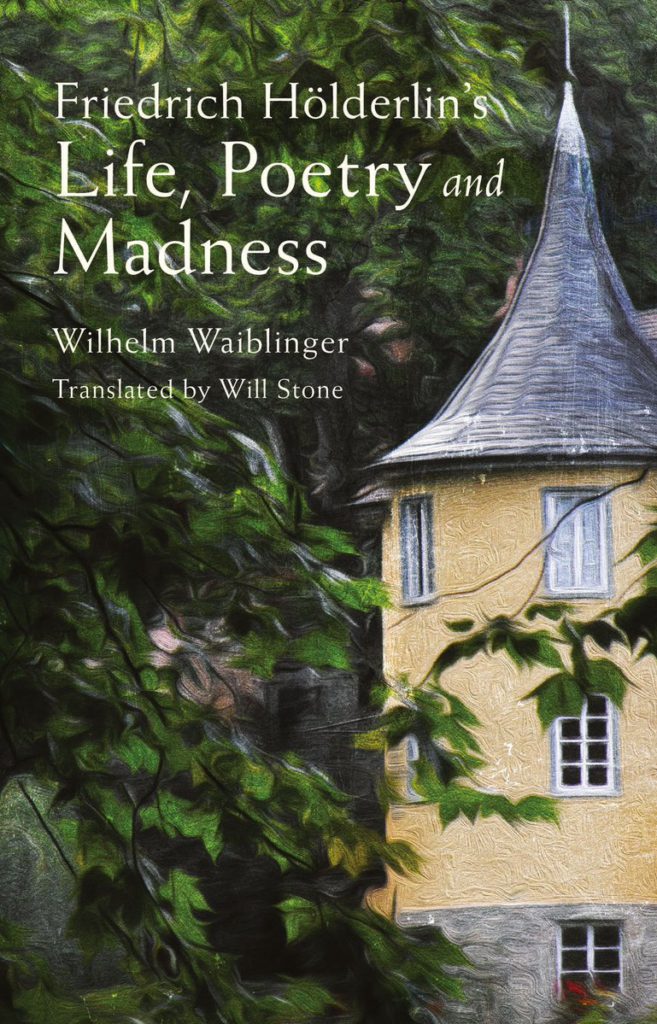

We had also written about Elizabeth Powers, concerning her review of Friedrich Hölderlin’s Life, Poetry and Madness, which has just been republished by Hesperus Press (translated by Will Stone).

She had written:

Although the inspiration came from the Greece-drenched enthusiasm of Winckelmann and Goethe, the ancient divinities were not, for Hölderlin, allegories or personifications, to be converted in art. Rather, prophet-like, he sought to bring them back to life in order to regenerate a world that, he felt, had grown old and lost its way. His earliest poems, from 1791, express the darkness of the world without such rejuvenation. “Half of Life,” however, published in 1804, without any Greek poetic apparatus, intimated where his own life was heading:

But oh, where shall I find

When winter comes, the flowers, and where

The Sunshine and shade of the earth?

The walls loom

Speechless and cold, in the wind

Weathercocks clatter(Michael Hamburger’s translation)

Kyriaco Nikias of the University of Adelaide wrote a letter about the various rewritings of the Greeks – also included at right. Thanks to Elizabeth Powers for passing this along!

Waiblinger visited the older poet and wrote a record of his visits.

Waiblinger visited the older poet and wrote a record of his visits.  She writes:

She writes: