Pop open the champagne! Happy Public Domain Day! ?

Friday, January 1st, 2021

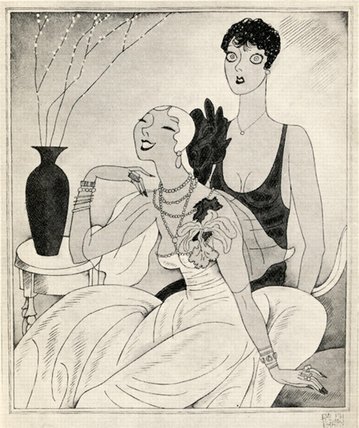

Ralph Barton’s illustration for “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.” It’s also in public domain now.

For those of us who keep an eye on such things – including bloggers, everywhere – we have some exciting news, and it rolls around every New Year’s Day. (So if you didn’t send cards this year, you’ll have another opportunity on January 1, 2022.) Happy Public Domain Day! What? You’re not excited? Well, I am.

As of today, F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s The Great Gatsby is up for grabs. So is Virginia Woolf‘s Mrs. Dalloway, Ernest Hemingway‘s In Our Time, and Franz Kafka‘s The Trial (in German). Excerpt as much as you like. Be my guest.

Plenty more books published in 1925 have entered the public domain, as of today. According to Jennifer Jenkins, a law professor at Duke University who directs its Center for the Study of the Public Domain. “And all of the works are free for anyone to use, reuse, build upon for anyone — without paying a fee.”

“Works from 1925 were supposed to go into the public domain in 2001, after being copyrighted for 75 years. But before this could happen, Congress hit a 20-year pause button and extended their copyright term to 95 years Now the wait is over,” Jenkin’s writes on the Duke website.

1925 was the year of seminal works by Sinclair Lewis, Gertrude Stein, Agatha Christie, Theodore Dreiser, Edith Wharton, Aldous Huxley … and, among musicians some works by Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, the Gershwins, Duke Ellington and Fats Waller, among hundreds of others. And 1925 marked the release of important works by silent film comedians Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd.

Free! Free! Free!

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of having work in the public domain. For example, can you imagine the holidays without It’s A Wonderful Life? That movie happened to be unprotected by copyright, so it was able to be shown — a lot — for free, contributing to its establishment as an American Christmas classic.

It also means books can be published more cheaply and made available for free online; that old “orphan” films can be preserved by archivists; that scholars can access and publish material more easily; that musicians can sample and experiment with the songs of an earlier generation and that classic characters can be given new life and new interpretations.

While the most successful creators often leave behind legal estates to manage the care (and finances) of their famous books, plays, operas and so forth, most aren’t so lucky. “For the vast majority of authors from 1925, no one is benefiting from copyright protections,” Jenkins tells NPR. Having their work enter the public domain is a way to keep it circulating in the culture for artists and historians to use for education and inspiration.

Overlooked Anita Loos

May we throw in our own bid for greater circulation? This year also marks Anita Loos‘s underrated classic and comic masterpiece of the Flapper Era, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes: The Illuminating Diary of a Professional Lady. Here’s what I wrote when we featured the book at Stanford’s Another Look book club for forgotten, overlooked, and otherwise neglected books way back in May 2013:

Edith Wharton called Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes “the great American novel” and declared its author a genius. Winston Churchill, William Faulkner, George Santayana and Benito Mussolini read it – so did James Joyce, whose failing eyesight led him to select his reading carefully. The 1925 bestseller sold out the day it hit the stores and earned Loos more than a million dollars in royalties. …

Everyone, of course, has heard of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but the short novel’s fame was eclipsed by the 1953 movie of the same name, starring Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell. Once the bombshell blonde vamped “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” the effervescent Jazz Age novel became a shard of forgotten history. Who has taken the send-up novel seriously since?

You can check out the catalog for 1925 copyrighted works here. Or check out the podcast for the Stanford panel discussion with Hilton Obenzinger, Mark McGurl, and Claire Jarvis here. (Claire placed the book in the tradition of the courtesan’s diary.)

Meanwhile, go ahead! Excerpt as much as you like! It’s on the house!

Postscript: The biggest fish of all: George Orwell is in public domain today. According to The Guardian: “George Orwell died at University College Hospital, London, on 21 January 1950 at the early age of 46. This means that unlike such long-lived contemporaries as Graham Greene (died 1991) or Anthony Powell (died 2000), the vast majority of his compendious output (21 volumes to date) is newly out of copyright as of 1 January. Naturally, publishers – who have an eye for this kind of opportunity – have long been at work to take advantage of the expiry date and the next few months are set to bring a glut of repackaged editions. …As is so often the way of copyright cut-offs, none of this amounts to a free-for-all. Any US publisher other than Houghton Mifflin that itches to embark on an Orwell spree will have to wait until 2030, when Burmese Days, the first of Orwell’s books to be published in the US, breaks the 95-year barrier. And eager UK publishers will have to exercise a certain amount of care. The distinguished Orwell scholar Professor Peter Davison fathered new editions of the six novels back in the mid-1980s. No one can reproduce these as the copyright in them is currently held by Penguin Random House.” Read the rest here.